#33: Central Asia, 1996 Three Weddings and a Picnic

If you read last month’s “preview,” you know I promised two weddings and a picnic, plus floating down the Ili River. When I got further into reviewing my family letters, I discovered there were three weddings reflecting the cultural changes coming to Central Asia. The old Soviet system was lingering, but religious rebirth was rising. And that picnic blended multiple traditions, old and new. So let’s focus on those events now and leave floating down the river for another time.

[Click on photos to enlarge.]

1996

March 19

Russell’s American junior colleague, Joseph Luke, is marrying his Kazakh sweetheart this weekend. Russell is best man, while I’m making a video and taking care of the cake.

March 28

March 28

My full-fledged respiratory infection relapsed, so it didn’t make sense for me to go to the wedding. As planned, Russell gave the groom away. From R’s description and the photos, it seems like a post-Soviet, civil ceremony offering impressive trappings to make up for the loss of Christian rites. Joseph and Gulbanu were married in the “Palace of Weddings” by a civil servant, along with ten other couples, all lined up with their wedding parties, one after the other.

The wedding party waits its turn, then the guests go up the backstairs to the balcony, while the bride, groom and their two witnesses climb the grand staircase. Up on the balcony, the apparatchik conducts a brief civil ceremony, and then it’s the turn of the next wedding party, who’re already lined up below. Despite this assembly-line atmosphere, the bride wears a fancy white dress (in this case with a two-meter train and purchased in Atlanta when Gulbanu was there on a study tour), and the groom wears a dark suit or a tux. The reception was at the recently opened, Western-style Marco Polo Hotel right out in the dining room, so all the hotel guests could admire the bride, I’m told.

June 6

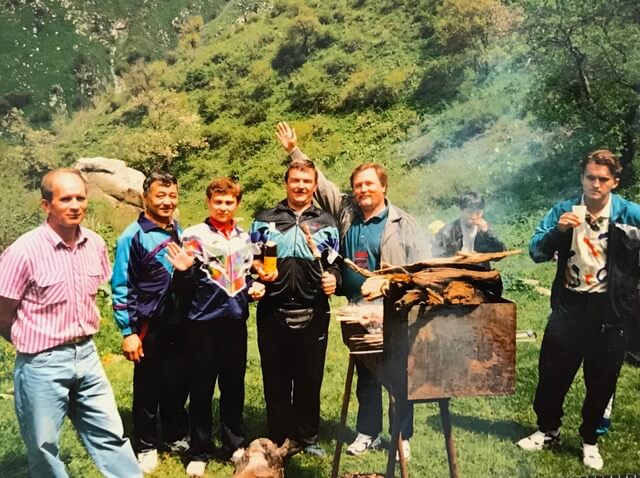

A fun office picnic last Saturday, despite all the things Mother Nature threw our way. We’d had to keep rescheduling because wintery weather kept lingering this spring. All last week was cold and rainy, and we were beginning to despair. But Friday was sunny, so we decided to take a chance. The result was a blend of Central Asian picnic with a few American bits thrown in.

We loaded the Niva (our Russian “jeep”) with the shashlik cooker, aromatic saksaool wood, a construction-size thermos of water plus various odds and ends. Then Russell went to the office to organize staff and families coming by bus in mid-morning, while computer-engineer Valodya, project-driver Serge and I headed off to the mountains at 8:30. They were both nervous as cats to have me driving. Most women here don’t drive, and those who do drive don’t drive Nivas. Of course, for Western women (and for me as a West Virginia gal), this is amazing, but many people here can’t imagine that a woman could drive at all, let alone drive into the mountains.

Despite their extensive advice on how to drive, I managed to get up into the Tien Shan without strangling either one. We arrived in a light rain, but we had a large piece of plastic to cover everything, so we started carrying the gear half-a-kilometer up the narrow valley. By the time we got everything organized, the sun was fitfully shining through, and we were glad for the warmth.

What a beautiful spot — at the top of the valley, a high mountain decked with the famous Tien Shan pines and fingers of snow. At the bottom, a giant boulder blocking travelers’ sight from the road below. In between, a green bowl with a stream — full of wildflowers, including wild peonies, which I’d never seen.

By the time the bus arrived, we’d assembled the shashlik cooker, burning the saksaool down to hot coals. It took only moments to thread the marinated meat onto metal skewers and start cooking. And a good thing too — all the people who came by bus were complaining about the cold.

Everyone got out their salads and other fixings, eating to their heart’s content. By the time we’d finished, the sun was out for good, and we played games to warm everyone up. Russell had brought his “bubble machine” which makes giant bubbles via an expanding loop. We also had frisbees, ring-toss and a cross between the two. Throughout, a band of musicians entertained, often with sing-along and dancing. We also played the R&N spoon game — two teams compete to pass a spoon with a looooooong string through their clothes. The prize was champagne, so they were pretty motivated.

By the end of the day, everyone seemed tired and happy. Most folks returned on the bus, including Serge riding with his family. Russell and Valodya got in the Niva with me, so the drive down was calmer than the drive up.

October 4

Attending Alisher’s wedding, we needed two long days of travel (down to Tashkent on Friday, back on Sunday) for a few hours of Saturday’s ceremony and festivities.

[As readers of the previous post may recall, Alisher Kasymov, project staff-member in Tashkent, organized our travels on the Silk Road. Alisher was raised in the Fergana Valley, famous in history and for its natural beauty. His family is most likely of Persian descent. When the Soviets occupied Central Asia, they purposely divided the Persian-speaking peoples, leaving some in Tajikistan and demarcating the border so that many were in Uzbekistan. Although the wedding itself was in the Soviet style, the festivities afterwards were in the tradition of Persian-speaking peoples.]

We couldn’t find a reasonably priced bus for the Almaty staff who wanted to go, so we decided to travel in two cars. We’d hoped to go in a Toyota Corolla with a driver named Valodya (none of the Valodyas previously mentioned) and in an Audi belonging to my driver, Sasha Morozov. But at the last minute, Sasha’s boss wouldn’t release him from his Friday duties, so he sent his friend Valerie (boy’s name here) with his Soviet-made car.

First, the challenges. We were all to meet at the office at 8:00, but Valerie showed up an hour-and-a-half late, because his clock was wrong. Then his car wouldn’t start, so Russell and Valodya pushed him with the hope that the engine was just flooded. Happily, the jumpstart worked.

Then we had to stop at Roza’s (project’s office manager) to collect a three-liter thermos of hot water which she’d forgotten. With almost no decent place to stop en route, that water was important. Valerie waited in the courtyard of Roza’s apartment building, while we went on to the first rest stop (two hours out of town) and waited 30 minutes there. When we got back together, Valerie’s car stalled again, so Russell and Vaoldya gave him another push-start.

At the next rest stop, Valerie got a flat tire. It was dark and cold, so changing it took longer than normal. Valerie’s car also had trouble climbing grades. Although this is steppe country, there are a series of passes, canyons and defiles to traverse. Our Toyota would breeze up an incline; then we’d sit and wait fifteen minutes for Valerie’s car to limp up and catch its breath.

Long story short: a 10-hour trip took 15 hours. We arrived in Tashkent at nearly midnight, having had no dinner.

Now the good news. We had glorious weather. The scenery was wonderful. When Dad and I travelled that same road last year, it was early summer, and everything was green. There were lambs and colts frisking with their mothers, and the streams were full of spring melt-off from mountain snows. Now there was fresh snow on the mountains, leveling off as if God had placed a ruler on the slopes and said, “Stop here.” The colts and lambs were half-grown and full of dignity. The steppes were no longer green but golden, and the stream beds were now full from autumn rains. In small towns, kerchiefed ladies sat by the side of the road selling apples, melons and pears. In the evening, young boys on the stocky horses of Central Asia drove herds of sheep and cows back home for the night, their animals often spilling across the road, so we had to slow down and honk our way through.

We stopped by a stream at 2:00 for a potluck picnic under a tree: boiled eggs, pasta salad, eggplant salad, two kinds of bread, cake, cheese, fresh tomatoes from our garden, fruit, two kinds of sausage, fried chicken, sodas, hot tea, juice and more.

We crossed the border into Uzbekistan without being stopped to show our passports!!

But we had a terrible time getting through Tashkent, although we had an excellent hand-drawn map from our staff there. The city was completing a major renovation, and all the old street signs seemed to have been taken down and not yet replaced with new ones. We kept stopping to ask, “Where is Abai Street?” Often the person asked didn’t know or gave us wrong directions. We finally made it to the office, and staff took us for late-night shashlik and then to an apartment they’d rented for the weekend.

This was one of the nicest apartments we’ve seen in Central Asia. Russell and I slept in the double bed in the bedroom. Oksana and Aziza, two of the younger female staff, shared a sofa-bed in the living room. Roza slept on a day-bed in the enclosed balcony. The drivers slept in another bedroom. The apartment had a very nice kitchen, toilet (separate room here) and bath. All this for $70 a night. We were next door to the apartment of David Stubbs, another project staffer there. His wife’s mother (who’d travelled with us) stayed with him, along with his mother who arrived the next morning from Bermuda.

For breakfast, we ate leftovers from the picnic. Russell and I went with David and his extended family to the “wedding,” while Roza, Oksana and Aziza went shopping. I put wedding in quotes, because it was nothing like any wedding I’ve ever attended in any country in the world. It’s as if the Soviets wanted to destroy all of a wedding’s joy — this system has been preserved, although changes are in the offing.

Tashkent’s Wedding Palace is a rather fortress-like building in the old Soviet style, very different from the elaborate one in Almaty. Inside was a long, low hall with four wedding rooms opening off it. Scores of brides and grooms and their parties were milling around outside and in the corridor. We thought we were late and rushed around trying to discover where Alisher’s wedding was. Finally, David checked with the registrar’s office and learned that Alisher’s party hadn’t picked up their papers yet.

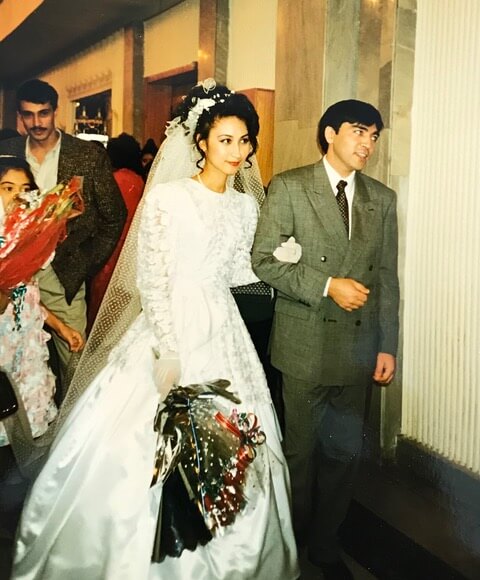

We stood and waited. We sat and waited. David and Russell wandered up and down the hall and outside, trying to find Alisher et al. Eventually, two hours late, they showed up. Alisher wore a beautiful suit which he and David had bought the day before. The bride may have been dressed in an elaborate Western gown with veil and gloves, but her face was right out of a Persian miniature.

We stood and waited. We sat and waited. David and Russell wandered up and down the hall and outside, trying to find Alisher et al. Eventually, two hours late, they showed up. Alisher wore a beautiful suit which he and David had bought the day before. The bride may have been dressed in an elaborate Western gown with veil and gloves, but her face was right out of a Persian miniature.

Zap! — we were rushed into one of the wedding rooms. An Uzbek woman in a suit turned up a cassette recorder playing traditional music. We hushed. She said about twenty words. Then Alisher and Anora signed documents and exchanged rings. The woman turned up a new cassette playing the wedding march, and that was it!

Alisher and Anora went to a small room nearby, where a mullah blessed their union, apparently a new addition since the fall of the Soviet Union. We were not admitted to this ceremony, which took about three minutes. Then we all went outside and took a series of photos at a series of traditional spots (which seems to be a long-standing convention not just in Tashkent but in Almaty too). And it was all over except for the reception that evening.

The Almaty team, plus David with wife and two mothers, went to a local restaurant for plauf, a local rice dish which I’ve described before. We sat outside on a roofed terrace and had a high old time.

Then back to the apartment for an hour’s rest followed by gussying up for the reception. The shoppers had returned, so we all had stories to tell. Roza, Oksana and I wrapped silver fabric around the microwave which we’d brought down from Almaty, pooling our money to buy a seriously expensive appliance here.

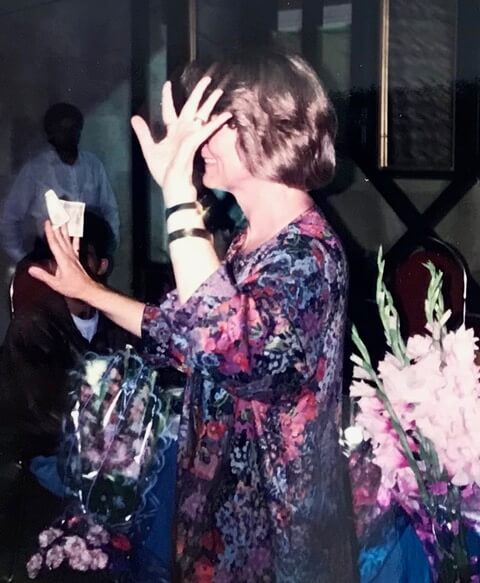

We all piled into the two cars and headed to a local restaurant for the reception, finding ourselves among the last guests to arrive. R&I were ushered to the table where the groom’s mother was seated and plied with all sorts of delicacies. After a while, the bride and groom appeared and were seated at a special table. The women of the two families began dancing in traditional Persian style. As they danced, guests rose to stuff paper currency between their fingers until their hands looked like large flowers. This money was then given, some to the band, mostly to the bridal couple.

Interspersed with the dancing were various toasts, one of which was given by RBS, who did our Almaty family proud. After Russell’s toast, we two were invited to dance, and it was my turn to do the family proud by knowing the traditional dances. It transpired that Uzbek-Persian dancing is very like Afghan dancing, so my time spent in Kabul paid off. Afterwards, the women of the two families came to congratulate me, saying they’d never expected an American would know how to dance like an Uzbek. I didn’t tell them I was dancing like an Afghan.

Interspersed with the dancing were various toasts, one of which was given by RBS, who did our Almaty family proud. After Russell’s toast, we two were invited to dance, and it was my turn to do the family proud by knowing the traditional dances. It transpired that Uzbek-Persian dancing is very like Afghan dancing, so my time spent in Kabul paid off. Afterwards, the women of the two families came to congratulate me, saying they’d never expected an American would know how to dance like an Uzbek. I didn’t tell them I was dancing like an Afghan.

The party ended shortly thereafter, the women of the bride’s family wrapping Alisher in a chopan, a long red velvet coat embroidered with gold and colored threads. The bridal couple left the hall, and almost immediately everyone else did too. Since the party had lasted only two hours, the Almaty team felt let-down. We’d only got up to speed when the whole thing was over. It may be that the groom’s family felt the same way: Alisher’s mother kept saying that their reception in their home town next week would be much better. We were invited to attend, but we can’t make them all.

The party ended shortly thereafter, the women of the bride’s family wrapping Alisher in a chopan, a long red velvet coat embroidered with gold and colored threads. The bridal couple left the hall, and almost immediately everyone else did too. Since the party had lasted only two hours, the Almaty team felt let-down. We’d only got up to speed when the whole thing was over. It may be that the groom’s family felt the same way: Alisher’s mother kept saying that their reception in their home town next week would be much better. We were invited to attend, but we can’t make them all.

After the bride and groom left, Roza went around collecting surplus food. Russell and I were very embarrassed by this and tried to dissuade her, but she said it was traditional for friends and family who had come a long way to be given the extra food for their trip home. That may be true at Kazakh weddings, but is it true for Uzbek marriages? We’ll never know. Hope we didn’t disgrace ourselves by scarfing up the leftovers.

The young folks went off to a disco to continue the party, while Roza, Russell and I went back to the apartment. It may have felt like the party ended too soon, but the old folks were glad to make an early night of it, given that we had to return to Almaty the next day.

We had few car troubles on the way home except for the hill-climbs, but we did have police trouble. Valodya’s car was right-hand drive, and we were pulled over four times before we got out of the city and a fine extracted on the spot (paid by RBS). The cops kept saying right-hand drive cars aren’t allowed in Tashkent. Valodya kept replying that no one had stopped us on the way in, so why were they stopping us on the way out? He’d show the receipts of having already paid a fine, but each new policeman said these receipts didn’t count. The consensus was that the cops saw a way to make a little money on a sleepy Sunday morning and were radioing ahead to their buddies so they could stop us too.

The other passengers lobbied for returning to Almaty without interruption, but Russell insisted on rest-stops every two hours in order to keep the drivers fresh. He bought watermelon and cookies, and the drivers seemed glad to have treats to  keep their energy up. (We noticed the passengers weren’t above enjoying the goodies.)

keep their energy up. (We noticed the passengers weren’t above enjoying the goodies.)

October 9

Perhaps the most exciting thing we did this week was attending a Russian Orthodox wedding at Nikolski Church. Dad has been there — remember the turquoise one with silver, onion-shaped dome? When he and I visited last summer, the church was well on the way to restoration after the fall of the Soviet regime, and that restoration is even further along today.

[We were told that when the Soviets conquered Almaty, they purposely stabled their horses in churches, including this one, desecrating the sanctuaries.]

The ceremony was in marked contrast to the one we attended last week in Tashkent. First of all, it was very long. Secondly, it was full of pomp and circumstance. After nearly each phrase, everyone crossed themselves (from right to left, the reverse of Catholic practice) and bowed. The priest was young (thirtyish?), but he led the service with great solemnity. He chanted a phrase in Russian, and then a hidden choir responded a cappella. They sang very well, and all the foreign guests later agreed that the music was perhaps the best part of the event. The bride and groom wore crowns at one point and led by the priest, three times circumambulated the lower altar where the ceremony was held. They also kissed a number of icons during the ceremony, an act integral to Orthodoxy. One sees daily visitors to the church making the rounds to kiss the icons.

Although we had aching backs and feet by the time the ceremony was over (no chairs in Russian Orthodox churches), we felt we’d experienced history as Christianity creeps back into the former Soviet Union. Many young people in particular are coming back to the various churches (Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox), seeking a spirituality in their lives which had heretofore been banned.

The groom was an American in charge of one of the election-reform projects, marrying a Russian woman from Semipolitensk up north (where the nuclear bomb facilities used to be). I must admit that the foreign guests were fascinated by the bride’s costume, which seemed a bit revealing in such a conservative church setting.

The groom was an American in charge of one of the election-reform projects, marrying a Russian woman from Semipolitensk up north (where the nuclear bomb facilities used to be). I must admit that the foreign guests were fascinated by the bride’s costume, which seemed a bit revealing in such a conservative church setting.

After the ceremony, we went to the groom’s apartment, where we were feasted with the usual cold dishes of salad, sausages and meats to start. Then there was bishbarmak [wide noodles with horsemeat] and assorted desserts. We sat opposite the U.S. Ambassador and her husband, talking about Afghanistan (where she and I both served when young), the latest Middle East crisis and current events in Kazakhstan. When the Ambassador got up to leave, that was the sign that the other Americans could depart, and we did. Most of the local folks stayed until the wee hours drinking and dancing, but we’re increasingly ready to leave that to the youngsters.

COMING NEXT MONTH

Kazakhstan 1995-1996

The Challenges of Living in Almaty:

Painting the zal, plus climate, cars and cats

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.