#32: Central Asia, 1995 Traveling the Silk Road with L.C. Swing

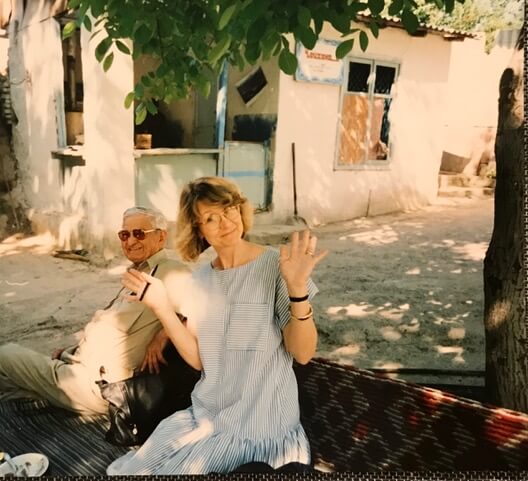

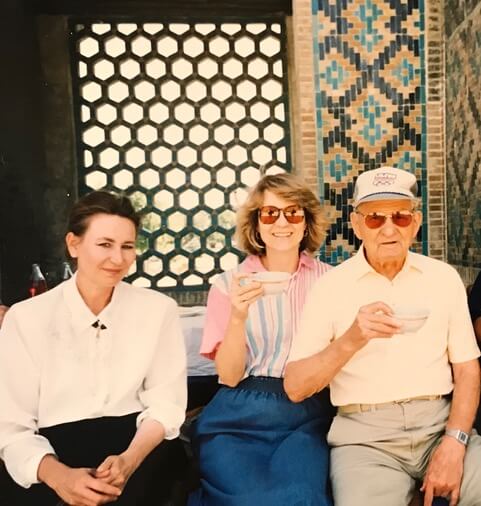

During our first year in Kazakhstan, Russell and I had a visit from that intrepid traveler, my Dad, Leonard C. Swing. We not only toured Almaty, its nearby mountains and steppes, we also journeyed to Tashkent, Samarkand and Bokhara on the Silk Road. In those days, modern tourist facilities in Central Asia had not really developed. The old Intourist hotels, never very good before the fall of the Soviet Union, were dismal after. Organized tours were nonexistent, but we weren’t really tour-group folks anyway. So through the kindness of friends, especially Russell’s junior colleague, Alisher Kasymov, we organized our own Silk Road trek. Here are edited excerpts from letters to family about Dad’s boyhood dream come true.

[Click on photos to enlarge.]

June 1

Dad arrived safe and sound today, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed too. He came off the plane at 5 a.m. full of p&v, and only a breakfast of yoghurt pancakes put him to sleep. Taking two night flights to get here is practically unavoidable — one across the Atlantic and one across the Eurasian landmass. He stayed overnight in Frankfurt en route, so he could get one good night’s sleep.

June 29

We left Almaty June 10 by jet for Tashkent, Uzbekistan, arriving in less than an hour. We were met by Alisher, the Uzbek staffer of Russell’s project there, and Rafzhan, the driver hired for our tour. Alisher had arranged the logistics for a true experience of the Uzbek reputation for hospitality. And Rafzhan was cut from the same cloth, as we shall see.

This hospitality started the first night, when we went to a chai-khana, a phrase I already knew from Afghanistan days (literally “tea-house”). We were served traditional grilled dishes of lamb, chicken and beef beside a fountain which rose right out of the river for some 30-40 feet! Alisher put us up in a boarding house (the Intourist Hotel leaves more to be desired than I can describe). We had a living room, two bedrooms, a large bath and entrance hall. Breakfast was included, and we ate it in a wood-and-brocade-paneled room while seated on modified camel saddles and watching CNN news. Take that, Intourist!

The next day, we toured Tashkent’s huge central bazaar, where we bought pistachios and saffron — more saffron than I’ve ever seen in my life and for just pennies. We also toured a couple of nearby mosques and the Fine Arts Museum (the collection of Islamic arts was particularly splendid). That afternoon, we went to another chai-khana where Alisher’s “uncle” (a term of respect for any older male relative) prepared classic Uzbek plauf (rice, meat and vegetables) for us. We sat on the traditional raised platform with a low table in front of us laden with plauf, local fruits, vegetables and flat bread. As is customary, we lingered for a long time, eating slowly and talking. By the time we were ready to get up, we could barely move, and it wasn’t only from sitting with our legs curled up.

The following day was just as full. First, we went to an old mosque and madrassa (Islamic school), where they are trying to rekindle the traditional arts. We bought a lot of gifts there, including a traditional holder for the Koran, intricately carved out of a single piece of wood and adjustable into six different positions.

Then we got a taste of left-over Soviet bureaucracy as we tried, and eventually succeeded, to get visas for Dad and me. (Russell already had one from a previous visit.) What should have taken one half-hour and one trip to the Foreign Ministry ended up taking most of the day and trips all over town. In the end, all was resolved, and after a stop at the wholesale bazaar to buy water, snacks and sodas, we left for Samarkand in the cool of early evening. Rafzhan drove four hours through irrigated fields of food crops and cotton, beautiful to view, but deadly to the Aral Sea which has been destroyed by this same irrigation. We stopped at a roadside chai-khana for a shashlik [described in previous post] dinner by the light of the full moon. When we arrived at almost midnight, our B&B hostess, Emma, was there to greet us and show us into our own apartment across the hall from hers.

Throughout the time we were in Samarkand, Emma proceeded to fill us full-to-bursting three times daily with every traditional Russian and local dish she could think of. I particularly liked “Aladdin” (pronounced all-ah-deen’), a kind of pancake made with yoghurt and sprinkled with powdered sugar and then drowned in homemade jam.

Our first day in Samarkand, we met our guide, Valentina, who teaches at the local Institute of Foreign Languages. She took us first to see the tomb of Tamerlane, the living Shiva of Central Asia, a conqueror who destroyed and created much. Also buried within the tomb is my favorite Central Asian figure, Ulugh Beg (1394-1449). Tamerlane’s grandson, he was both scientist and ruler, yet was eventually executed, because orthodox Muslims thought he was trying to learn things which should be known only to God.

Our first day in Samarkand, we met our guide, Valentina, who teaches at the local Institute of Foreign Languages. She took us first to see the tomb of Tamerlane, the living Shiva of Central Asia, a conqueror who destroyed and created much. Also buried within the tomb is my favorite Central Asian figure, Ulugh Beg (1394-1449). Tamerlane’s grandson, he was both scientist and ruler, yet was eventually executed, because orthodox Muslims thought he was trying to learn things which should be known only to God.

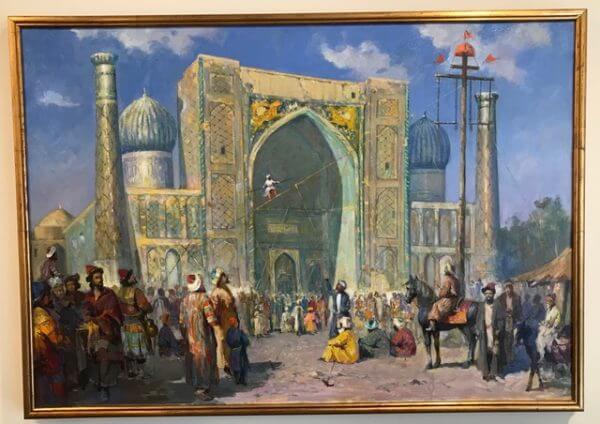

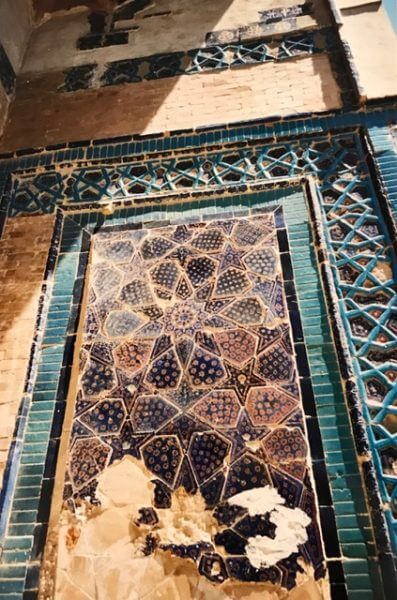

We continued to the Registan (pronounced with a hard “g”) to see one of the great wonders of the world: a huge plaza surrounded on three sides by enormous mosques and madrassas (one of them built by Ulugh Beg!). A Western writer said that for Europeans to have matched the feat, they would have had to build three Gothic cathedrals around an equal plaza. All are beautifully decorated, and they’re being restored now that Uzbekistan is in charge of her own destiny again.

However, some of the materials and techniques are not appropriate and may in the end cause more damage than help. This kind of restoration, which one sees throughout the world, is controversial — whether to restore or just preserve. I’m a preservation person myself. Just save what’s there now and show me a painting of how it might have looked. It’s too risky otherwise: what’s there may be destroyed, as is currently happening at Angkor Wat.

Our last day in Samarkand, we visited the Bibi Khanum mosque and madrassa. Bibi Khanum, Tamerlane’s favorite wife, commissioned this beautiful complex, including a huge marble support for a Koran so large it could be read from the balcony above. The former Chinese princess is credited by some as having brought the secret of silk manufacture out of China. (Another legend says she fell in love with her architect.)

Next door to the complex is Samarkand’s bazaar, where I found traditionally-patterned fabric perfect for curtains in our Almaty dining room.

We went on to the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis on the outskirts of the old town. An amazing alleyway of tombs, each more richly decorated than the next, all in tiles of blue and green and turquoise and white and yellow. It was like being inside a jewel. Next was Ulugh Beg’s observatory, where he and fellow scientists made calculations far more sophisticated than anyone else was doing at that time. His observations and theories put him in the same league as Galileo and Kepler.

We went on to the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis on the outskirts of the old town. An amazing alleyway of tombs, each more richly decorated than the next, all in tiles of blue and green and turquoise and white and yellow. It was like being inside a jewel. Next was Ulugh Beg’s observatory, where he and fellow scientists made calculations far more sophisticated than anyone else was doing at that time. His observations and theories put him in the same league as Galileo and Kepler.

The day continued with a drive through the original Sogdian walled city, now in ruins and awaiting the archaeologists. Those of you who remember your Western Civ probably recall that it was the Persian Sogdians who ruled this part of the world when Alexander the Great came through and conquered everything in his path. It was an amazing feeling to be on this fortified hilltop and imagine that Alexander had been here too.

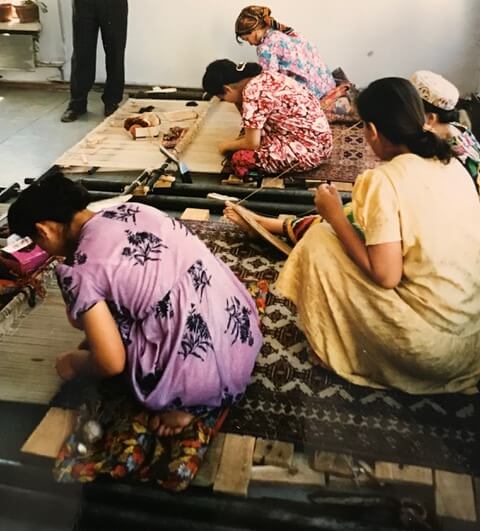

Finally, we visited an atelier where a refugee Afghan family is teaching local girls to make carpets again. This skill was mostly lost under the Soviets, so it’s ironic that the Soviet incursion into Afghanistan has made possible the rebirth of an ancient art in Uzbekistan. We saw one we really liked, but the price was far too rich for our blood — champagne tastes and beer pocketbook. At least we know they’re making the good stuff.

Finally, we visited an atelier where a refugee Afghan family is teaching local girls to make carpets again. This skill was mostly lost under the Soviets, so it’s ironic that the Soviet incursion into Afghanistan has made possible the rebirth of an ancient art in Uzbekistan. We saw one we really liked, but the price was far too rich for our blood — champagne tastes and beer pocketbook. At least we know they’re making the good stuff.

Our three-day Samarkand sojourn over, we left in the cool of early morning for Bokhara, an important Silk Road stop to the west, situated in an oasis between the Black and the Red Sands. Again, we drove through irrigated fields, except for 30 minutes. That half-hour revealed how arduous the trek must have been in ancient times when it was six days of desert tracks instead of four hours of highway.

We were greeted by host Sasha, a former Russian soccer star who has returned to his native city and opened a guest house with his wife Lena. A typical Bokharan house built around a courtyard shaded by vine leaves, it features a small garden in the middle with fig trees and the ubiquitous Central Asian divan.

We were greeted by host Sasha, a former Russian soccer star who has returned to his native city and opened a guest house with his wife Lena. A typical Bokharan house built around a courtyard shaded by vine leaves, it features a small garden in the middle with fig trees and the ubiquitous Central Asian divan.

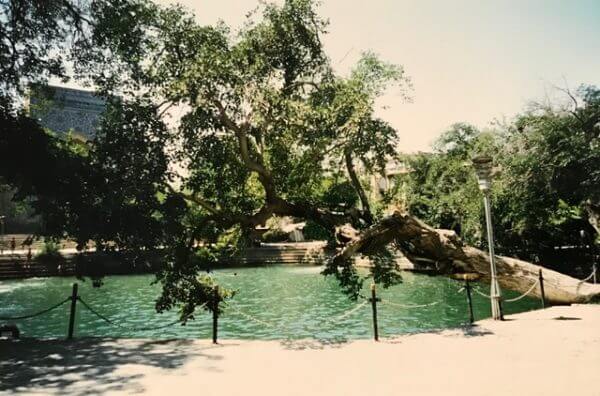

Sasha doesn’t serve lunch, so Rafzhan took us to the old town center for a traditional meal of shashlik, etc. I was enchanted by this public space, so symbolic of an oasis in the desert. Five hundred year-old mulberry trees surround a reservoir where children splash and play. On three sides are ancient madrassas, and the fourth side houses a chai-khana where old men sit and gossip: a glimpse of medieval life out of the Arabian Nights. After lunch, we turned in some laundry and turned into bed ourselves for a nice nap before dinner.

The next day, we were met by Noilla, who works at the museum but moonlights as a guide. We started at The Ark, which has nothing to do with Noah. It’s the ancient citadel where so much history took place, not the least of which was the imprisonment and eventual beheading of two officers on Her Majesty’s Secret Service in the 19th century. (If you like, read The Great Game, an account of intrepid British, as well as Russian, spies during the years when the two world powers were striving for control of Central Asia.) We visited the emir’s audience hall, a beautiful mosque and the actual six-meter-deep pit where the two officers fought off roaches and rats just to eat their pitiful ration.

We returned to the old town center and toured the madrassas, most of them no longer active schools. The Soviets closed them all down with one exception, which was supposed to serve all the Muslims in the Soviet Union (nowhere near enough for everyone). In the Middle Ages, Bokhara was a center of learning, and students came from as far away as Muslim Spain to attend one of these institutions. Many famous scholars of the Muslim world were there, including Avicenna, the “Father of Modern Medicine.” A few madrassas have been opened to the public, but most house small shops selling arts and crafts, plus at least one chai-khana. Nevertheless, they’re breathtaking inside with their pointed arches, cloisters and elegant tiles.

Our sightseeing day ended with a visit to one of the oldest mosques still standing on earth. Built in the 12th century on the foundations of an 11th century mosque, it’s far below the current street level. In fact, this was a place of worship for centuries before that. Archaeologists found the foundations of a 5th century Zoroastrian temple below the 11th century foundations and a Buddhist temple below that. Who knows? — perhaps Stone Age people worshiped here as well. Now, unfortunately, the building houses a shop of mediocre rugs, but we heard that the local Muslim community has petitioned to have it restored and re-dedicated as a mosque. I hope they succeed.

After a good night’s sleep, we went first to an ancient Muslim mausoleum. Established in 907 AD, its architecture bears Sogdian influences. However, it also pioneered architectural techniques which were used for the next five centuries. If that’s not enough to make it noteworthy, it appears that Zoroastrian fire reverence may have continued at this site despite Muslim, Russian and Soviet conquest. In front of the mausoleum is a slab with a hole reaching back into the earth. Even today, people light candles and put them in that hole, perhaps not knowing the antecedents for the practice.

[Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest religions, is based on the teaching of the Persian prophet Zoroaster (recorded 6th century, BCE). Its tenets of monotheism, messianism, free will and judgement after death plus concepts of heaven, hell, angels and demons, may have influenced other religions, including Judaism and Christianity, as well as Northern Buddhism and Greek philosophy. Fire is the Zoroastrian symbol of purity, and a sacred fire is maintained in temples. Perhaps the best-known adherents of the faith today are the Parsis of India.]

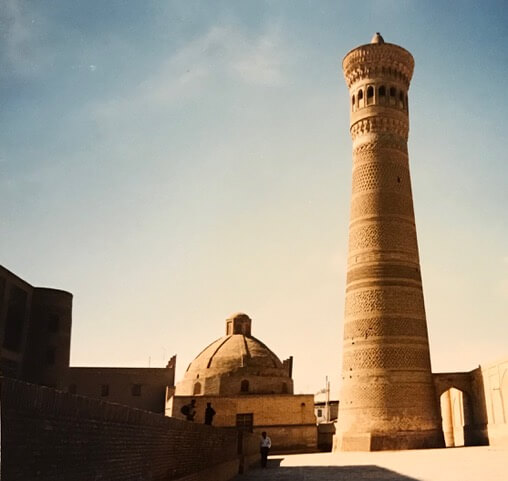

We also toured the Kalyan Complex with its 47-meter [1125′] minaret. It was so impressive, rising out of the desert plain, that Genghis Khan spared it when he destroyed most of the rest of Central Asia. Later, it was used as a place of execution with criminals being thrown from the heights (resulting in the appellation, “Tower of Death”). Now on the UNESCO World Heritage list, it’s protected from destruction.

We also toured the Kalyan Complex with its 47-meter [1125′] minaret. It was so impressive, rising out of the desert plain, that Genghis Khan spared it when he destroyed most of the rest of Central Asia. Later, it was used as a place of execution with criminals being thrown from the heights (resulting in the appellation, “Tower of Death”). Now on the UNESCO World Heritage list, it’s protected from destruction.

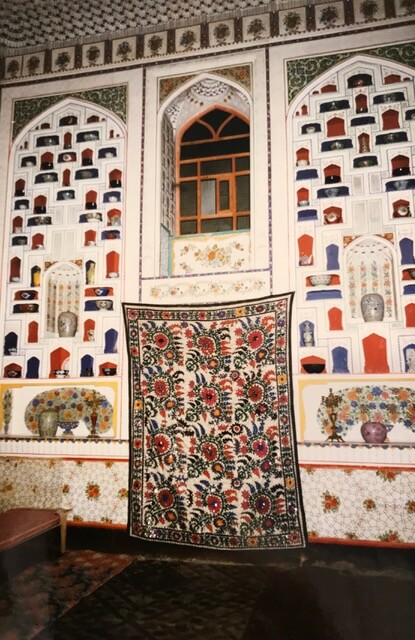

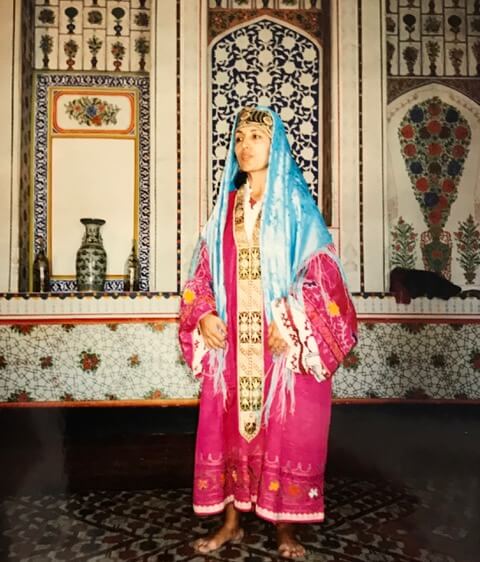

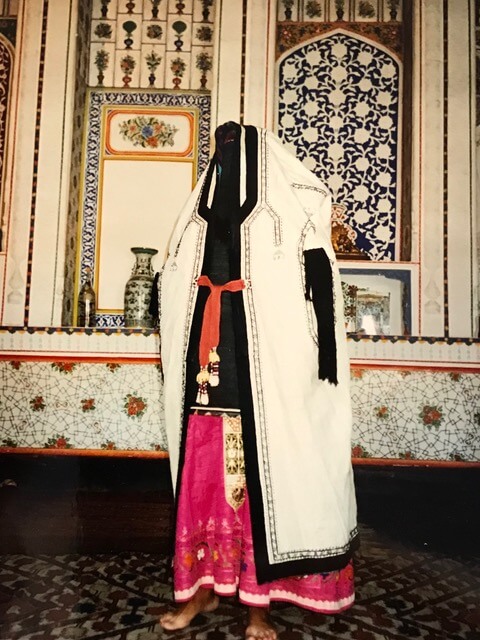

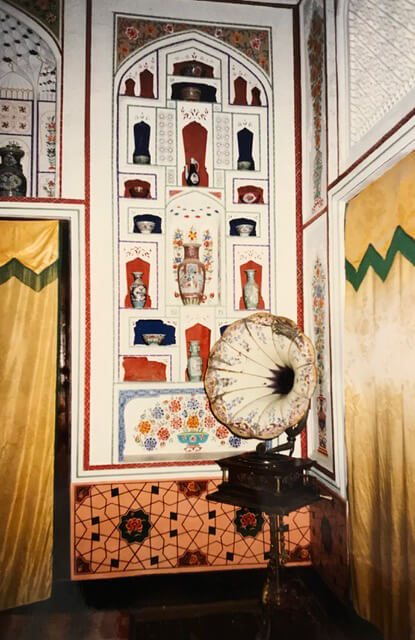

We especially enjoyed our visit to the 19th century (?) house of a wealthy merchant with caravanserai (facilities for travelers and their animals), harem courtyard and an ancient victrola. Noilla modeled what the ladies of the house would have worn both at home and when venturing out to the bazaar or calling on friends.

Our sightseeing ended with a late lunch hosted by Noilla’s “auntie.” This elderly lady lives in the old quarter behind The Ark in a modern, middle-class home, an interesting contrast to what we’d just seen. She fixed typical Bokharan plauf with all the trimmings, and we ate so much we didn’t have room for a burp.

This is probably a good place to note how taken everyone was with Dad, from all the folks in Almaty, to Alisher, to Noilla’s auntie. They all remarked on his stamina, his intellect and his curiosity, refusing to believe he was a day over 65. At the same time, they gave him the great deference which people here feel is owed to those in their golden years. Lovely to see Dad get his due.

[As I recall, that impossibly red-headed widow, Emma, was particularly interested in Dad, inquiring whether — having buried two wives — he might be interested in marrying again…]

That night we packed and prepared for the next-day, all-day drive back to Tashkent. We stopped at Emma’s in Samarkand for one last fabulous lunch and arrived at our Tashkent boarding house in time to get cleaned up for dinner.

On Monday, the 19th, Russell flew back to Almaty for project commitments, while Dad and I found the perfect gift for friends back home — six kilos of just-picked apricots, a real treat because Almaty is still too cool to harvest apricots. We left Tashkent early the next day, traveling by car to Chimkent in Kazakstan with Rafzhan’s brother. We really missed finishing the trip with Rafzhan, who got called back to his regular job. He’d been a truly fine humsafar (traveling companion).

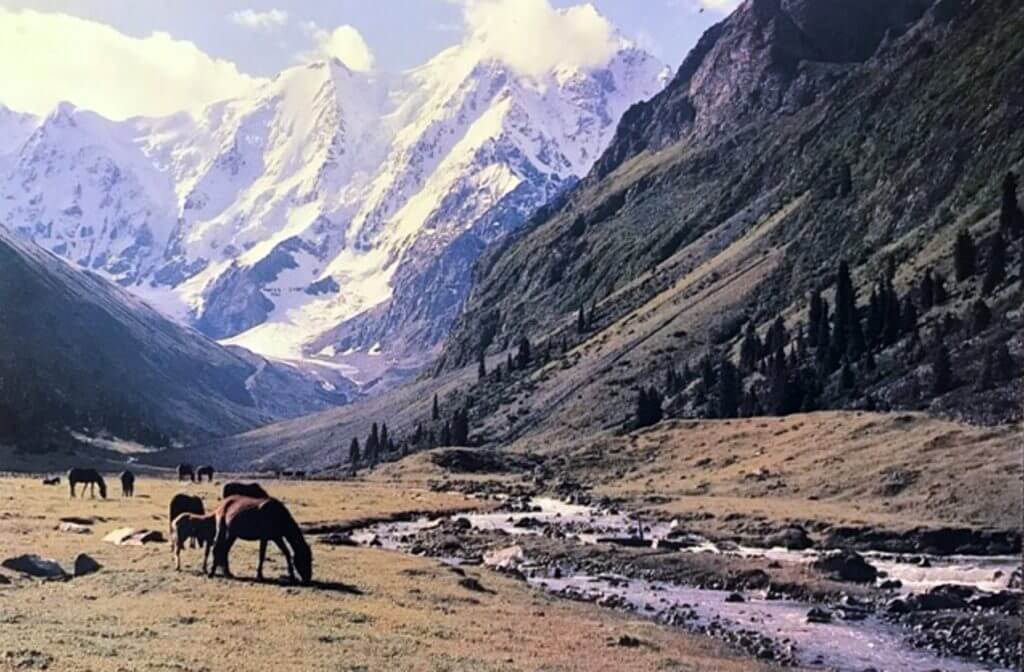

At Chimkent, we switched to Almaty-friend Sasha’s car. He’d driven down the day before to meet us and bring us home. What a trip that was — very long, very tiring, but also very beautiful, riding through early summer along the Silk Road, snow-capped mountains to our right, steppes stretching as far as the eye could see on the left. Now and then, we would enter a shimmering emerald valley with a river running down from glaciers. By the time we got back to green and cool Almaty (a welcome change from brown and hot Bokhara), we’d traveled over 1000 miles of the Silk Road. Even though we did it in comfortable cars, staying in pleasant quarters with good food, we could still appreciate what an ordeal it must have been for all those men and women who struggled along the route for millennia, carrying luxuries back and forth between East and West.

COMING NEXT MONTH

Kazakhstan, 1995-1996: Central Asian Life

Two weddings and a picnic

Floating down the Ili River

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.