#30: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1995 The Challenges Continue.

As summer turned to fall, friends began asking for an update on how we were doing in Central Asia. Here’s the good news and the bad news, edited from the first section of my response.

[Click on photos to enlarge.]

At the time we lived in Kazakhstan, the capital was Almaty (SE corner of country).

THE SUNSHINE-SWING CHRONICLES

or How to Live in Central Asia and Learn to Love It

Here followeth the story of how Big Russie and Little Nannie moved to Almaty, had many adventures and survived to tell the tale. Some is told in recollection and some retrieved from our weekly letters to the family.

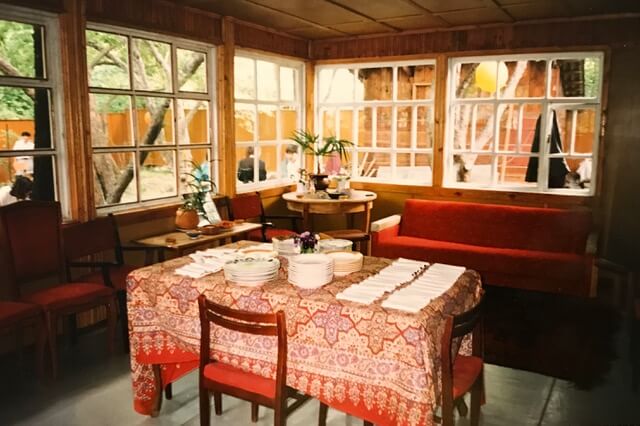

Americans visitors say our house looks like their idea of a dacha. Built by an engineer who emigrated from St. Petersburg to found the Ministry of Mines 60+ years ago, it retains most of his original furniture. The rooms are painted in the strong colors favored by northern Europeans (to help them through the long winter nights?). The present owner is the grandson, a man of about 35 who lost his mother and child in a tragic car accident, followed by an acrimonious divorce. He doesn’t want to live alone in the house and thinks it’s wonderful that some crazy foreigners want to help him renovate it and pay him rent. We have two bedrooms, a studio/office apiece, a living room, dining room, kitchen, bath and verandah (an enclosed summer room where we spend April-September). All this on 3/4 of an acre of enclosed land full of apple, pear and cherry trees.

When we moved in, the yard was literally a garbage dump of old lumber, pipes, broken furniture and other stuff. In an economy of scarcity, you save everything in case you might need it one day. That broken chair still has three good legs, and you might want one to repair another chair. We agreed with landlord Sasha that he could select the things he most wanted to save. Then we would select some stuff for our use, and the rest would be carted off.

When we moved in, the yard was literally a garbage dump of old lumber, pipes, broken furniture and other stuff. In an economy of scarcity, you save everything in case you might need it one day. That broken chair still has three good legs, and you might want one to repair another chair. We agreed with landlord Sasha that he could select the things he most wanted to save. Then we would select some stuff for our use, and the rest would be carted off.

With the help of Valodya, a computer engineer whose factory hasn’t paid him in months, we’ve turned the garbage dump into gardens. Valodya works part-time with us to earn hard currency. He’s not only an experienced gardener (most people here grow food crops to save money), but also an amazing handyman. So far, he’s built two benches for the terrace, fixed the plumbing, put in new wiring and new ceiling lamps, installed appliances, created a vegetable garden from nothing, fixed derailed drawers, reupholstered chairs, painted a small room…and that’s only the highlights.

Creating free-flowing gardens a la Gertrude Jekyll was a real challenge. The Russian style lines everything up like soldiers — trees, flowers, pathways, etc. And ornamental gardens have been mainly reserved for public spaces, while individuals use every speck of available private land to grow food. No one here had ever heard or seen anything like I was proposing — naturalistic drifts of flowers and shrubs. Five months later, people come by to peek in because they’ve heard that the funny American has a new kind of garden. Most of them like it.

Some House & Garden highlights from my weekly letters to family

3/28/95

We signed the lease with landlord Sasha, agreeing who would be responsible for what. Among the things I’m responsible for: finding and buying appliances, finding pigment for wall paint and finding kitchen tiles. The latter two items will be bought by Sasha, but I’ll shop and choose. The appliances — clothes washer (no dryer to be had in Almaty), kitchen stove, refrigerator and hot water heater — are my total responsibility.

In the States, you’d go to one or two appliance stores and one or two hardware stores and you’d be done, right? Wrong! At least wrong for Almaty. There’s no such thing as either an appliance store or a hardware store here. Instead, every store carries lots of things: some food, some clothes, a couple of appliances, a few dishes, maybe a can or two of paint, a few rolls of wallpaper, some pots and pans, two ironing boards and an electric space heater. The exact items and quantities might differ, but that’s the general picture. Our guess is that capitalism is so new that shopkeepers just buy one or two of everything they can find, hedging their bets that somebody will want to buy something they have.

I’ve been going from pillar to post looking at appliances — only one or two in each store, countries of origin as diverse as the peoples of the earth, none of them comparable, almost none with manuals or guarantees. Some are brands you’ve heard of — Samsung, Phillips, Siemens — but others you’ve probably never heard of and never will again — Bombini, Arar, Moscow (guess where that one’s from…). We don’t want anything produced in the former Soviet Union — shoddy quality — but we’ll take South Korean, Japanese, made-in-the-USA or any European brand.

The current hot water heater is over 20 years old and looks like something you might have seen in rural America during the 30s. It’s gas, not really vented and very scary. We wanted electric, but there aren’t any in Almaty, at least not the kind you and I think of when we hear that term — no large tank of water heated by an electric coil. Instead, there are machines about as big as a three-ring binder which pass water over a coil and heat it, but not much. I’ve visited shops all over the city and far out into the suburbs to see Israeli, Italian, Turkish and English versions of this little gem. None of them heat water to the temperature that you’d want for a bathtub or to wash dishes.

Finally Saule (“Sewl-ya”), my language-teacher and translator, heard about an importer with big electric heaters. So we went to their office…in the Central Museum (like running a business out of the Smithsonian!). Government buildings are now renting space to private businesses. This raises all sorts of interesting questions, but at this point, it’s just part of the economic transition, especially with the government out of funds. Saule helping, I had a nice chat with the three guys who run the business.

“What size?” I ask.

“Any size you want — 25 liters, 50 liters, 100 liters — what do you need?”

“Do they sit on the floor, or are they mounted on the wall?”

“Whichever you want.”

“What country are they imported from?”

“All countries.”

“Can I see one?”

“I’ll show you a picture.”

“Can I see the photo today?”

“No, at the end of the week. We’ve just moved in, and we haven’t yet unpacked all our documentation.”

“Are you saying that you’ll show me a picture, and then you’ll order the heater and import it?”

“Ah………….yes.”

“Do I pay on delivery?”

“No, you pay when you order.”

“What if I don’t like the machine once it comes?”

“Well, I guess that would be too bad for you,

“Let me ask you something: Would you buy a bride just from looking at her picture?”

They laugh.

“Right. You wouldn’t buy a bride, and I wouldn’t buy a heater.”

We all had a good laugh, but I was no nearer to having a hot water heater.

During our traipsing around Almaty, we’d seen a modern gas heater made in Russia under a Japanese license. A very long story short, and I haven’t even told you half of it, we compromised and decided to buy this modern heater. It’s really a geezer with a small tank, but that’s what everyone has. At least it should be safer that what’s already in the house, and it’ll heat better than the small ones.

Now, what about the pigment? “What pigment?” you ask. Paint here is sold in one color, white. Then you buy pigment and mix your own color. There’s no cute little machine like Home Depot. If it’s water-based paint, you buy a packet of powder, dump and stir. If it’s oil-based (forget latex), you buy a tube, squeeze and stir. But there’s no pigment in Almaty. There used to be lots of paint and lots of pigment, but now there’s almost no paint and definitely no pigment. I’ve been to countless shops and bazaars in all sections of town, and everywhere we’ve heard “Nyet,” “Nyet” and “Nyet.”

This lack of formerly available items is due to the breakup of the Soviet Union. When it was all one big country, all sorts of commodities and raw materials moved everywhere. Now the supply lines are broken, so there’s “nyet pigment” to be had anywhere.

Finding a stove, fridge and washing machine is similarly challenging. A couple of weeks ago, I actually discovered some that would do; i.e., they were the right size to fit the rather small spaces but big enough to do the job with the right features. For example, I’d like an oven with a thermostat, so I can control the temperature. Most ovens here are either “on” or “off.” But I found one! — gas burners and an electric oven, the perfect combination. Wrong. There’s no heavy-duty wiring in the house, so the stove has to be all gas. I finally tracked down an Italian stove, all gas with an oven dial that reads 1 through 8. Now, if I can find an oven thermometer, I can learn what each number means in terms of temp.

The fridge continues to be a terrible problem. It can’t be wider than 60 centimeters (24″), but I need as much interior space as possible for all our official entertaining. This means a tall, thin one. In fact, such refrigerators do exist, and I saw one. But it’d been sold, and as usual, there was only one, and no one knows when the store might have another. The search continues.

The washer must be no wider than 60 cm., and movable to sit beside the bathtub, hook up to the tap and heat the water to the desired temperature. I also want it to spin the clothes and empty into the tub, both automatically. “Centrifuges” (the term here) are not so common.

I was lucky to find both washer and stove in the same store. So Saule and I went next door to the exchange service to change my dollars into tenge (“tyen-gyeh”). The clerk didn’t have enough tenge for that sum. Up the street in the cold spring rain to the next exchange. He didn’t have enough either. Finally, our project driver told us about an exchange that was down an alley, turn right, through a garden and into a small shack attached to the back of a big building. Low and behold, there was a legitimate, licensed exchange with all the proper accoutrements and a good rate.

Back through the rain to the store. Studiously ignored by the clerk (common experience here). Finally found the manager.

“Could we buy these two appliances, please?”

“Nyet problem.”

“Could someone help our driver carry them out to the van?”

Nyet problem if we were willing to pay extra.

“Could we have the manuals, missing hookups, dials and gas burners please?”

“Nyet problem……ah……no……We’ve got the accessories for the washer here, but the ones for the stove are at home for safekeeping. You can buy the stove tomorrow.”

“Great. We’ll take the washer, please.”

“Nyet problem. 30,000 tenge, please.”

“Can I have a guarantee?”

“Tomorrow.”

“Okay, I’ll pay for the washer and take it now. You can give me the guarantee tomorrow.”

“No, you will have to take everything tomorrow.”

So, inchallah, I’ll borrow the project van again, and we’ll trek over there again, and maybe we’ll get the stove and the washer then. In the meantime, I’m carrying around 1000s of tenge in 500-tenge notes. I need a camel.

On with the paint search. Saule heard that someone at the “business center” (Not sure what that means) had pigment to sell. We drove down to the bazaar quarter and went into a large building. I had to show my passport. (Why? Military installation? Govt. building?) The lady who checked documents looked at every page of my passport and stroked the cover.

Finally she asked Saule what my nationality was.

“Amerikanka.”

“What a beautiful passport,” she said with wonder in her voice and eyes.

Up to the second floor to the designated door. It’s locked. Saule starts knocking on doors, but no one seems to know where the missing person is or when he will be back. We’re advised to stand in the hall and wait. We do. After a while, Saule loses patience and knocks on some more doors. Finally, someone says to go to the other wing of the building and inquire at the director’s office. So we go up hill and down dale, across corridors suspended above the street, through dusty hallways with empty offices and peeling paint, up several flights of stairs to the director’s office. He’s in a meeting. Please wait. We do. Then the director comes out, surrounded by sycophants. He ultimately frees himself from the hangers-on, and his secretary motions us to follow him into his office (big, paneled, rather tired). We explain our reason for coming. He says to go down the hall and talk to the man in charge of such things. We do. He’s surrounded by his own sycophants. Saule tries to tell him why we’ve come.

He abruptly tells us to wait, shuts the door in our faces and takes his sycophants with him. We stand and wait in the hall. Saule begins to sigh with frustration or fatigue. Finally the sycophants come out, and Saule pushes her way in. She tells him our business, and he answers angrily. She relays that he doesn’t have any pigment for sale. Suddenly a woman covered in paint drops appears. Saule asks her about pigment. She says yes, there is pigment for sale, but it’s only for water-based paint. Saule looks angry and resigned. Back through the corridors to our driver who’s been waiting for over an hour.

“All this time wasted,” Saule says, “It will take us a hundred years to learn how to do business.”

I actually don’t think so. It took the mainland Chinese only about a decade, and the Lao were well on their way within the two-and-a-half years we were there.

A few days later, one of the project drivers says there’s a paint store at the stadium. I’m thinking there was a water-heater importer in the museum, so why not a paint-importer in the stadium? Off we go, looking for door number 21. Finally we find it — in the former toilet! They’ve converted one of the toilets into a store where they’re selling Chinese paint brought across the border by who-knows-what means. This paint comes pre-mixed, but they don’t have any of our colors. None of us needed to use the facilities, so we got back in the car and continued our search.

Another driver said he knew of a bolshoi (large) store up on the hill, so we drove through a traditional neighborhood of small cottages to a pink philharmonic hall with white columns. Inside was the closest thing Almaty has to a real hardware store — tools, rolls of wallpaper, all sorts of imported cleansers, bathroom fixtures, shower curtains, etc. etc. And paint! Good quality, imported from England! Right now, they’ve only got white and green, but by the end of May, they hope to have the full panoply of colors. That’s a bit late for me, but maybe I’ll come back then and look for something to replace the electric blue of my study. I bought Russell his longed-for pruning shears and descended the hill, feeling I’d seen the future, and it was good.

7/20/95

On Monday, just as Vaoldya was leaving after a full day’s work, Sasha came running around the house, bearing a large branch from a cherry tree, brimming with fruit.

“Nensi! Nensi! See what I’ve brought! (In broken French, the only language we truly share.)

Oh, how nice, I thought, he’s pruning a tree and giving me the proceeds. I abandoned working on my book and started picking the branch’s cherries. Then Sasha brought another branch. And another branch. The yard was filled with branches. The new-grown grass was churned to mud with trampled cherries everywhere. And still the branches came.

Valodya abandoned his plans to go home and helped. We filled plastic bowls and wash basins full. Then we went to investigate.

Disaster! Sasha was cutting down the ancient cherry tree outside Russell’s study, the only tree on that side of the house, protecting us from the afternoon sun. I tried to protest. It wasn’t right to destroy such a beautiful old tree. The house would be hotter just as the warmest months arrived. It was making a hell of a mess, and it was 5:00; when were we to find the time to pick all these cherries and clean up the mess?

“Je comprends, je comprends” was the only answer I got. He understood my arguments, but he wasn’t going to do a damn thing about it until the tree was dead and gone.

So Valodya and I spent 3 hours picking cherries off dead branches, trying to at least save the harvest. We then dragged the bare branches beyond the garden wall and stacked them beside the creek. We cleaned up all the debris, including the smashed cherries which had to be painfully gathered, one by one, by hand. Then we watered the grass, hoping to save it from death and destruction.

When Russell arrived home at 7:00, he found two tired campers, sharing a large beer, nursing our sore backs and discussing whatever made Sasha do it. The best theory was Valodya’s final summation. “Sasha arteesteeyeh” (my poor rendering of the Russian for “Sasha is artistic,” meaning fey and impractical).

Several days later, Russell and I had another thought: Sasha wanted to put in a new exhaust pipe for the basement boiler which feeds our radiator heat. It was going to exit near the tree. The welder’s sparks would fly. Sasha was afraid the tree would catch fire, so he cut it down.

We gave cherries to our driver and housekeeper. We offered some to Valodya and family, but they already had a harvest from their dacha. Russell took two washtubs-full to the office, where they were a thrill to all and sundry. The rest I made into cherry preserves and brandied cherries and cherry juice (the latter with R’s help, smashing cherries through a colander with his fist). I cannot tell you how many hundreds of cherries I sorted and pitted by hand. If I ever have to do it again (God forbid), I’ll just make brandied cherries from all of ’em — by far the easiest. And tastiest too.

My driver later said it used to be a capital offense to cut down a tree in Almaty. During the thirties, when the Soviets were planting trees all over town in an effort to ameliorate the climate, they literally shot people who cut down trees. It seems a bit extreme but maybe worth merit in our case…

7/27/95

Last Saturday, Russell and I went with Valodya and his daughters to Talgar en route to their dacha. The plan had been to have a picnic on the upper reaches of the Talgar River and then proceed to their dacha to help pull weeds. However, a soldier stopped us from entering the narrower part of the valley (in hopes of a bribe, we all thought). Since Valodya was raised on the lower Talgar and used to hunt, hike and fish all up and down it, he was affronted to think that he should pay to go there now. R&I also felt we didn’t want to encourage bribery, so we all agreed that we’d just hike up there one day. Apparently, you don’t have to pay a bribe to hike.

Such is the reality of transition in the former Soviet Union, where factory workers and teachers and soldiers haven’t been paid in months because the government is basically bankrupt. The private sector is still struggling to get established, so people are caught in the middle between a government which can no longer pay and a private sector which can’t yet pay. Hopefully, these dark days won’t last too much longer.

We snatched victory from the jaws of defeat by going rock-hunting on the middle Talgar, where it’s still a broad river rushing amid millions of stones deposited over the ages from the mountains high above. Lower down, the river has been channeled into irrigation, but where we stopped, there were still plenty of both water and stones. We not only picked up some beautiful rocks, we conceived the idea of returning later with a truck and getting lots of rocks to complete the paths in the garden. Valodya later went whole-hog and said we ought to pave the area outside the verandah with rocks, so we’d have a nice place to put our feet while we sat on his new benches.

8/10/95

On Friday morning, a huge Soviet Army truck pulled up outside, driven by Sasha’s friend Nikolai. I climbed up into the cab — a big stretch — and we were off to pick up Valodya and daughter Julia (“yoo-lee-ah”), daughter Katya having decided not to come. When we got to the crossroads where V&J were waiting, I got into the back of the truck with Julia. Valodya gallantly protested this arrangement but finally acquiesced. He was the one who knew where we were going, so it only made sense to put him up with the driver.

We’ve had such a magical summer, not too hot, not too cold, breezes most of the time, and that’s the kind of day it was. We were soon out of the city and driving along country roads lined with old fences and wildflowers. Julia and I were bouncing around but doing okay, perched on wooden pull-down benches under olive canvas.

We arrived at the Talgar around 10:30 and started picking rocks (sort of like picking flowers, only harder) — mostly beautiful pink-and-gray granite and black basalt. Nikolai took off his shirt and worked on his tan, while the three of us worked on filling the back of the truck. When we finally judged we’d done enough, we stopped for lunch. V&J had brought fresh vegetables from their dacha, and I had juice, Coke, cheese, crackers and cookies. I don’t think I ever ate a tastier cucumber than I did that day on the Talgar. It was somehow like the first time you eat a truly fresh banana — no comparison to what you buy in the stores.

Valodya then took his regulation dip in the mountain stream. Folks here believe that bathing in super-cold water is good for you. I decided that a little sunbathing was more my speed, so I leaned against a rock while Valodya froze his tutu. Both of us ended up happy, I think. On the return trip to town, I had a sort of satori experience, a feeling of deep contentment and peace as I rode with Julia, my feet propped on rocks. “This is what I want,” I thought, “to work hard outdoors, wear heavy shoes and ride in the back of trucks.”

We got home, unloaded the rocks and had some juice. The unloading took almost as much time as the loading, because we had to be careful not to damage anything here. When all the rocks were piled in front of the garage, Nicolai, Valodya and Julia took off, and I took a long soak in the tub.

Sasha suddenly materialized, saying that all the rocks had to be moved, because the workmen were coming on Monday with a big tank for the garage, and they had to be able to get in. This would hold auxiliary fuel for when the city-supplied gas fails, as it does now and then. Russell and I spent Saturday and Sunday moving rocks bucket-by-bucket through the garden and around to the verandah side of the house, on the theory that Valodya would start by finishing the walkways in the garden at the front of the house, then do his proposed terrace outside the verandah.

By Monday, when the tank arrived, the entrance to the garage was free. When Vaoldya arrived, he decided to do the terrace first, so the rocks were not in the best place after all. He said not to worry, he’d start on the other end of the terrace. Two weeks of part-time work later, he was done. It really does look wonderful, water-smoothed stones gleaming in the sun. Then V did the walkways, and our garden is starting to look like something out of “Horticulture” magazine.

I reviewed what I’ve done so far before going on with writing these Chronicles, and I’m reminded of something important about living in another country: things don’t happen the way they do at home. Pretty obvious, right? Yet that’s part of what makes the international life interesting and fulfilling. The challenge of solving problems in another country is in itself fascinating. The minor necessities of daily life are never routine. Challenging events aren’t hassles but adventures full of surprises and opportunities for learning how things work here. It’s fun!

COMING NEXT MONTH

Kazakhstan, 1995: Chronicles, Part 2

A healing shaman and a stitching doctor.

Work setbacks and triumphs.

Fun and games

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.