#2: Peace Corps/Afghanistan, 1968-69

That first experience of culture shock during Asian Seminar 1964 pretty much inoculated me for the rest of my life. By the time I applied for Peace Corps training after obtaining my Masters in Television Production at Boston University, I knew what to expect and had some ability to deal with the discombobulation of entering a new culture. I’d also learned that being busy and productive was critical to having a positive experience.

When the invitation to join Peace Corps/Afghanistan came, I was disconcerted to learn it was to train with a group who would be smallpox vaccinators. Only women were in this group, because only females could touch women in the highly traditional Afghan culture. In my application, I’d written that I wanted to work in some form of educational media. I talked about this disconnect with my parents, and we concluded that maybe Peace Corps wanted to add me to the group in order to use my media skills to help achieve the goals of the eradication project. So I packed up and headed for training first in Arizona for desert experience and then in Colorado for its high altitude.

Most of us arrived in Arizona wearing nice dresses and heels. Once we’d been bussed from the airport to the training center and registered, we were told our quarters were down a sandy road. Off we struggled, barefoot and lugging suitcases through the gathering twilight. Welcome to the new world: better dig out your jeans and hiking boots asap.

Here are some excerpts from letters and aerograms home:

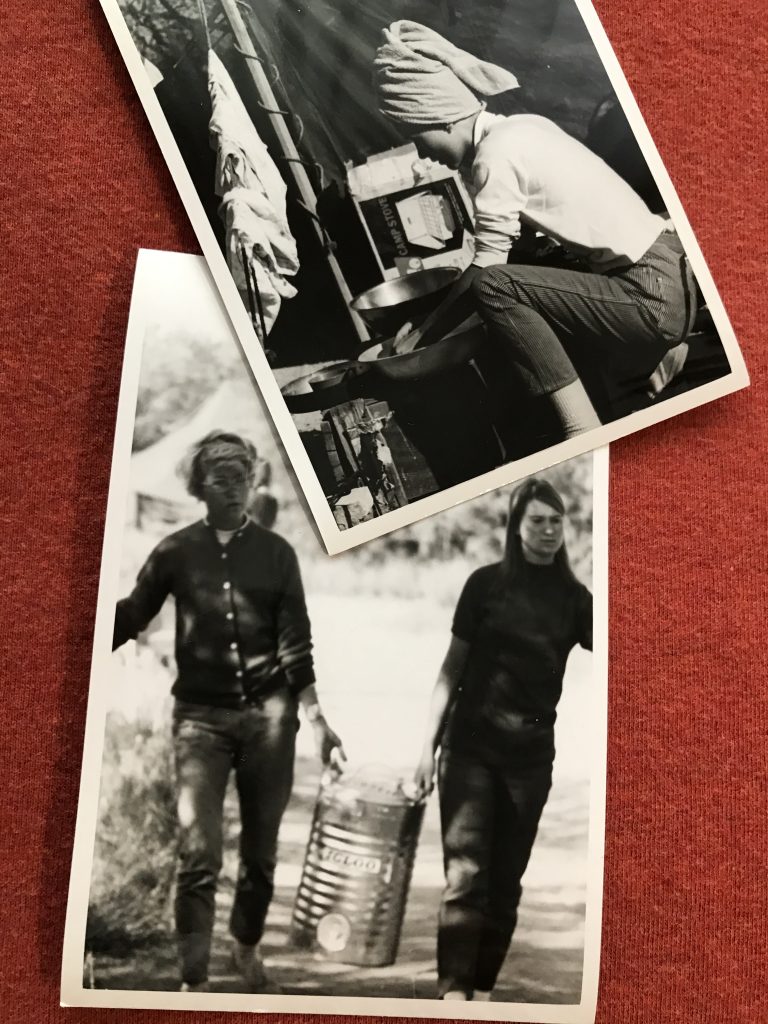

Hauling water so we can wash in a tin basin.

October 21, 1968 Arizona

We’re living in tents way out in the middle of the desert. We’ve got a shed with a hole in the floor for a john (squatting required) and a tin basin to wash self and clothes. We’ve got bunks and sleeping bags, and that’s about it for accommodations.

The country is seriously spectacular! I had a real thrill just flying in on the plane. Although we’re living in the desert, we’re surrounded by huge mountains. Tomorrow we’re riding horses up into those mountains for an overnight camping trip. We’re to be on horseback most of the time in Afghanistan, which I rate as super.

The third week in Arizona, we’re going to live with Apache families and participate in a different culture.

Everyone here is very nice and helpful. We’ve gotten along fabulously. There are only girls in this project, but the ratio of PC men to women in Afghanistan is 3:1, so that’s no big hang-up. Actually, it makes it easier to go without makeup and real baths, plus there’s no conflict over dating, etc.

Just in: [Because of my history of repeated throat infections, PC staff] want to schedule surgery to take my tonsils out in Boulder [Colorado] while the other trainees are living with Apache families here. I’m disappointed to miss that, but they think it wouldn’t be wise to have the operation and come back to recuperate in a dusty tent. There’s also the possibility that I’ll have to drop out because of [the surgery]. Naturally, I’d be crushed and hope we can work it out.

We start classes today, so I’ve nothing to report there yet.

The more I hear about the project, the more pleased I am to have been invited. We’ll really be seeing a lot of the country and people. Approximately 85% of the time, we’ll be out in the hinterland and the rest will be in Kabul. When we travel, we’ll go with a couple of Afghan counterparts and a policeman, so we’ll be well taken care of. The project has enjoyed unprecedented success; Afghanistan Smallpox Eradication is the darling of Washington, and the U.N. is stepping up support services.

November 9, 1968 Colorado

Tomorrow I go for tests at the University Hospital in Boulder. They’ve arranged for a specialist, so there’s nothing to do but sit back and wait for Allah’s will.

This 3-star motel feels totally plush. You can’t imagine how lovely it is to have a double bed and hot bath after two weeks in the desert.

Another girl dropped out of the program. The first quit to get married, and this one left because it was too tough. We’re really getting down to separating the sheep from the goats, and the stress is beginning to show here and there. I feel more like sticking it out each day. I’ve yet to be depressed or really pooped out.

After the first week, they re-divided the Farsi language classes according to ability, and I ended up in the first class. But I’m the worst in the class, so I can’t get too swell-headed. It’s been a long 7 years since I took language, and you forget those learning skills.

Yesterday, my cross-cultural group gave a presentation on environmental sanitation, as if it were to villagers. The local staff and Washington brass went ape over it, so I guess those two years in Boston are beginning to pay off.

The jodhpurs [that my mother had suggested sending] are a nice idea, but we’ll be wearing native dress most of the time, like we did in India, for about the same reasons. As a matter of fact, the Afghan costume looks very much like the salvar kemiz I brought home from Asian Seminar — baggy pants and a tunic.

I’m down the road doing my laundry. I looked pretty funny trudging through this resort town with a backpack full of dirty clothes, but it sure beats a suitcase! I now have my own bedroll, canteen and backpack and look like a typical PC trainee — no makeup, slightly rumpled and very tan.

November 12, 1968 Colorado

Throat healing splendidly. PC doctor checked it out yesterday, and he said it was “beautiful.” One surprise, tho: the surgeon removed my uvula. Don’t really know why, but it’s gone.

We’re getting a semi-record snowfall, and we literally wallow from class to class.

Next Sat. is mid-term evaluation of trainees. The Field Assessment Officer mentioned that 4 or 5 people are having trouble, but he intimated that I shouldn’t worry.

I don’t know if I mentioned it before, but there are a couple of things I thought of for Xmas: a multi-blade, super-duper hunting/pen-knife; a butane lighter and fuel supply; a couple more white cotton turtlenecks.

November 27, 1968 Colorado

Wild things have happened. At mid-term [evaluations], the training staff and Washington rep felt that my technical background, “dynamic personality” and “leadership ability” could be put to better use and that I would be more content in a project other than smallpox vaccination.

They went back to D.C. and came up with the following. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) gave Afghanistan a completely equipped film lab, but the support contract was dumped. The Afghan head of the lab was trained at Brookings Institute and is extremely well-qualified in every way. However, few Afghans know how to use the equipment or the art of film-making. They need mid-level people who can train the Afghans and translate story ideas into shooting scripts for adult ed.

Two volunteers are working there now, and Washington has sent a cable to Afghanistan to see if they would take me as a “special placement” in the film lab. This would mean that I would stay with this training program and continue studies in Farsi and cross-cultural skills. When we get in-country, I would go work at Afghan Films as a Peace Corps Volunteer.

I couldn’t be more pleased at the prospect. It’s exactly what I want to do. I can’t dare to hope that it would work out — it’s so perfect!

December 7, 1968 Kabul, Afghanistan

Wild things continue to happen with my life in Peace Corps. When we arrived last Wednesday, it was to find that no one here was expecting me. Lesson #1 in cross-cultural contact — the cable didn’t get through.

The local Peace Corps staff and the Peace Corps Volunteer who works at Afghan Films think it would be a real mistake for me to work there. The lab is currently on winter schedule (9-12, 2-3:30), and they’re awaiting budget approval, so all they have to do for the next 4-6 months is one 10-minute newsreel a month.

The PCV and the French volunteer are both demoralized with reading the paper all day every day. The Frenchman says it would be a mistake to waste a good background when there’s nothing to do.

In June, Columbia Pictures may come over to film “The Horsemen” with Yul Brynner and Anthony Quinn. But that is still in the negotiating stages, so it isn’t clear Afghan Films would be involved. When MGM filmed “Caravans,” they ended up going to Spain because of the red tape.

PC advised checking out some other possibilities until Afghan Films gets back on its feet, so I followed through. The Ministry of Agriculture is organizing an audiovisual center under their Extension Service, and today I was made Director of Radio Services with a staff of three and my own office. I will also start a bi-monthly journal for extension agents, published in Farsi and Pashtu. I’m actually helping them organize the whole A-V dept. from the ground up, including the organization chart and chain of command.

The Ministry of Health also needs similar technical assistance. I’ve made it clear to PC that I want to work directly in my field. If these projects fall through because of politics or lack of funds, I don’t want to stick around [just to be] a PCV in Afghanistan. They concur and would pay my way home.

January 15, 1969 Kabul

I leave Friday for four days in Jalalabad, where we’re going to have a workshop for extension agents. Jalalabad is in the south and at a lower elevation. Winters are mild there, and I’m looking forward to it. [Kabul is located at 6000 feet or more, depending on where you are in the city.]

We’ve made a lot of friends, and our social life has been swinging — USAID movies, films at the British Council, birthday parties, etc. The other night, we were invited to dinner with an Afghan family. We had a lovely time, but they were very westernized, so our first visit to an Afghan home was not typical.

The job is pretty interesting, and I really have more than I can do, so there’s no chance of boredom. The big thing is to introduce some efficiency and technical know-how into the operation. I’m working closely with AID people and Americans at the University.

I’m taking Farsi for an hour everyday with a tutor provide by Peace Corps. He’s a good teacher and conscientious, so we’re making some headway with my thick head.

The vaccinators are out in the provinces for a few weeks of in-country training. We’re anxious for them to return, because this experience will surely make a difference in their commitment and perceptions. Some will be strengthened and challenged; some will go home. They are our good friends, and we are anxious to see what has happened.

* * *

As you might imagine, there were events I couldn’t or wouldn’t write home about. Sometimes I didn’t want my parents to worry. On other occasions, the descriptions would have been politically unwise in case my mail was opened, or the space on an aerogram was just too small to write everything. Let me add some memories here, so you’ll have a fuller picture of my life in Afghanistan.

Like most Volunteers, I travelled all over Kabul by bike — not too significant you might think, until you picture us navigating on roads of icy, rutted snow. More than once I had a tumble, often in traffic, and felt the thrill of wondering if I was going to make it.

As a consequence, I often walked if the distance wasn’t too great. One day, I was returning home as the sun was setting, when a car pulled over and an Afghan man in Western dress offered me a lift. Women Volunteers had been warned not to accept such proposals, because there had been instances of physical danger. This risk was partly due to some female “World Travelers,” who were known to saunter down the middle of the street, stoned and half-dressed by Afghan standards. The result was that some Afghan men were totally certain we were all promiscuous. So I said to the Afghan driver, very politely in Farsi, thanks but no thanks. The Afghan began to berate me in English, saying how typical I was of “snotty, slutty foreigners.” I walked faster, and his car kept pace while he continued to curse me. Then he screeched to a halt, got out of the car and came towards me. Thank goodness for growing up a tomboy in the West Virginia hills. I took off like a shot, weaving through various obstacles, until I arrived at our house just down the block.

It’s important to note that this was the only experience I had of such behavior from Afghan men. All my co-workers were male. They would invite other colleagues and me to their houses for dinner, where I first dined with the men, treated as a seemingly gender-less fellow professional. Then I would be invited to eat with the women in another part of the house, because when non-family men were present, the sexes had to be separated. I am one of the world’s smallest eaters, so I ended up uncomfortably stuffed but invigorated by both conversations. I especially remember a wrinkled grandmother telling me she felt sorry for Western women, because they had no sister-wives to help with taking care of the house, satisfying the man and raising the children. Maybe she had a point?

One more meal comes to mind. It was in a rural area outside Jalalabad, where Afghan colleagues, the USAID officer and I had stopped at a chai khana (tea house) for lunch. After following the Afghan custom of pouring hot tea in and over our cups and tossing it out (an excellent way of sanitizing the cup), we’d settled down to tea, lamb shish kebabs and whole wheat naan (flatbread). A short, stocky Western man in an overcoat and astrakhan cap came over to chat, focusing on why we were there, what had we seen in our travels, etc. After he left, the AID guy leaned over to whisper that the man was a Russian spy. At the time, I thought that sounded paranoid, but the subsequent Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 always made me wonder.

* * *

January 21, 1969 Kabul

Sit down, pour yourselves a drink and hang on. This may get held up in the mails (Ariana Afghan Airlines was wiped out by 3 wrecks) but I’ll send it anyway to give you some warning. I’m leaving for home sometime next week.

We’re playing galloping govt. here, and the A-V project is about to fall through. Everything is rather mixed up at present because govt. officials are going and coming. It may be 6 months to a year before things begin moving in my field.

I talked it over with PC staff, and we’re all in agreement that it’s better for me to go back to the States than to sit around for maybe a year with no guarantee that there would be anything to do then.

I’m not sure yet exactly when I’ll be leaving, but I’ll phone you from New York, and Peace Corps/Washington will also probably give you a call with exact details when they’re firmed up. This whole thing is rather complicated, so I won’t write more through the open mails, and we’ll have long talks when I get home.

At present, I’m thinking of getting a job in New York or on the West Coast. I’ve been away from my craft too long, and I’m anxious to get involved where it’s really happening. Both PC and AID have said they could use me in places like Malaysia and the Philippines where the situation is more stable. I’ll think about it, but having to start all over with three months of new language and cross-cultural training is less attractive than getting back in the saddle again and doing the thing that I went to school to learn, because I love doing it.

Don’t feel bad. I’ve had a great time, and I don’t regret one minute of these past months. How many other people my age have had a chance to visit Afghanistan, knowing the language and connecting with people?

I was deeply disappointed to leave Afghanistan. I had fallen in love with the country and her people. And I’d had such high hopes for one media project after another. That experience of projects falling apart turned out to be more typical than I might have imagined at the time. I was to learn that power plays among funding agencies, competing government bureaucracies and personality conflicts are just as common in the developing world as they are in the USA. But something good was to come of my return to the States. Not only would I get real-world experience working with CBS in Los Angeles, but I’d also meet the man who would become my life-partner living and working overseas. If Afghanistan hadn’t fallen through, this would never have happened.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.