#16: Laos, 1991 – Settling In

For years, I’d been operating with the philosophy that, as a consultant, I could focus on the beneficiaries of a project, working around the politics of bureaucracy and the challenge of team mates who were some combination of poorly prepared, racist and/or not focused on empowering participants to be effective in their own milieux.

But repeated incidents like those in Somalia, Guyana, Nairobi and Cairo were taking their toll. After a particularly demanding and disheartening experience in Pakistan, I spent the hours on the long flights home realizing all these efforts had done me in. I was completely burnt out.

When I returned, Russell reported he’d been offered a one-year assignment managing a multi-faceted project in the former French colony of Laos, but he’d turned it down. He knew accepting the offer would likely mean my becoming a “dependent spouse” instead of an active development worker. He’d done this once before, when he was being considered for the post of Project Manager in Pakistan. He’d been told that I, who’d been considered one of the most successful project consultants over the years, would no longer be permitted to work in the program because of the appearance, if not the temptation, of nepotism.

But that was then. This was now. I no longer wanted to be a consultant in international development. Almost without thinking I replied, “Is it too late? Call ’em back.”

So began a new chapter in my life, as I tried to figure out what I was supposed to do next. Write? Certainly teachers since high school had been encouraging me to follow that path. Volunteer work? I’d had no experience in that role since college. Nurture a home and garden in a new setting? Work I dearly loved, but would it be enough?

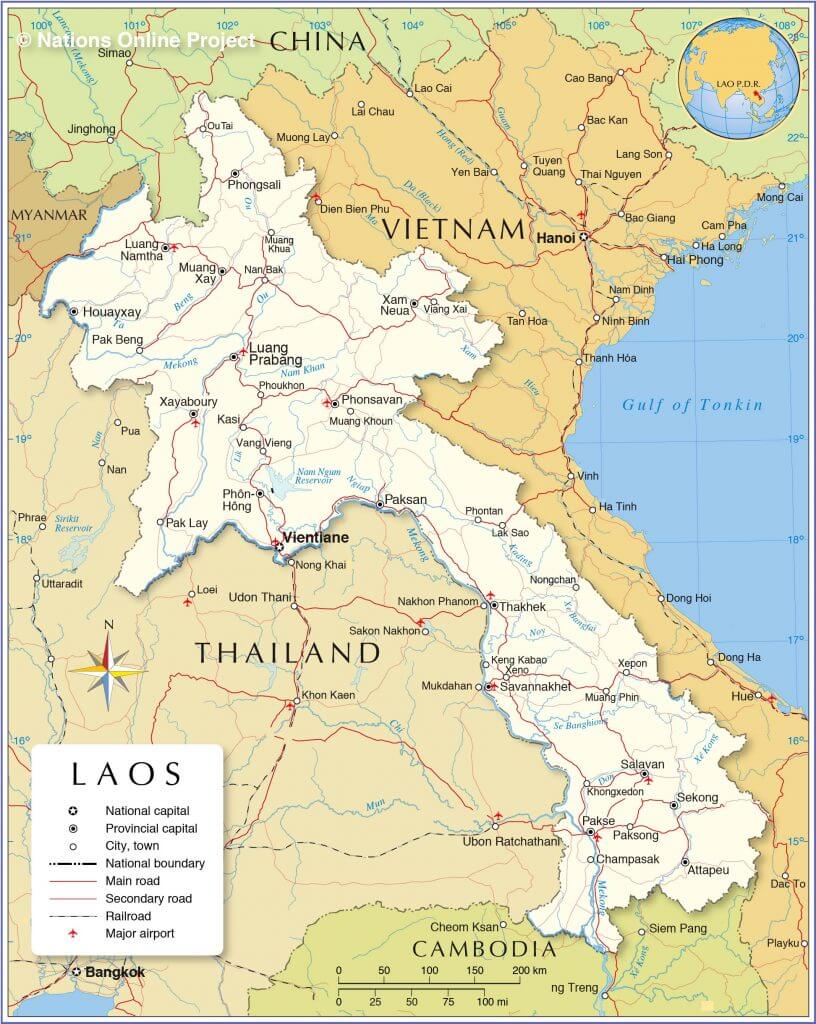

Before long, Russell was Coordinator for the World Bank/United Nations Development Programme’s “Open Door” project in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. [That was the country’s official title, but just about everyone said “Laos” in everything but official communications.] The project’s goal was to help the Lao government attract and manage foreign investment after 15 years of post-war isolation. In addition to drafting modern laws and regulations, Russell’s team of long-term and short-term experts would train Lao counterparts and organize investment promotion conferences in Laos and throughout the Asia/Pacific region.

Russell left for the capital city of Vientiane two months before my departure. That’s not unusual for couples living overseas. In fact, since at least the 19th century, it’s been termed “Pack, Pay and Follow.” Nessun Dorma still soars in my memory of those two months. I played The Three Tenors tape over and over as I selected the few things Russell’s contract would allow us to ship and organized storage for those worldly possessions we would keep. The rest found new homes in a garage sale.

Prior to leaving our house in Fredericksburg, VA, I met with the editor of the local paper about my contributing short articles on my experiences in Southeast Asia. Fortunately, he welcomed my proposal, and I climbed on the first of many planes knowing I had at least one writing project to help me move forward on a new track.

Here are excerpts from weekly letters I wrote to our family on my laptop.

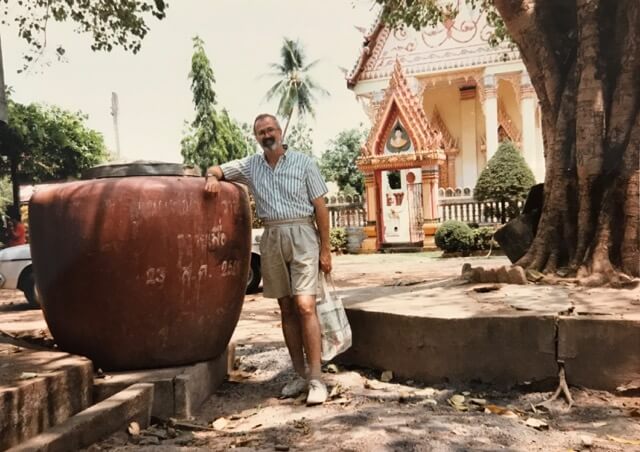

March 7

I’ve been here 4 days, and I’m full of impressions. Vientiane is both better and worse than I’d expected. After more than 15 years of socialism, things are a bit shabby. Most of the buildings downtown could use a coat of paint and some sprucing up. By contrast, the temples are in good repair and quite striking despite efforts to decrease the influence of religion. Consumer goods are more than OK. You can find just about everything you need to set up house and feed yourself.

The situation is very different from when we lived in East Africa. Arusha was neat and tidy, but consumer goods of all kinds were almost impossible to find — butter, eggs, meat, flour, rice, clothes, etc. That’s not the case here. Food is good and plentiful; there are blue jeans and all manner of clothes in the market; or you can have things made.

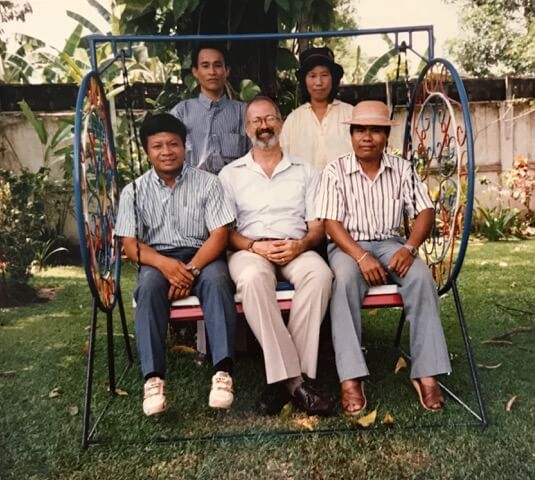

We have three people helping with the house: Mme. Long, housekeeper, who cleans, does laundry and prepares terrific meals; Mr. Kham Sing, the gardener/handyman; and Mr. Vilay, the night watchman. It’s maybe a mark of the state of the economy that all three make more than high-ranking government officials here. They ride motor scooters and send their kids to good schools, thanks to working for foreigners.

The modes of transport here, in order of importance, are: foot, bicycle, motor scooter and car. There are very few of the latter, although they’re starting to come out of the woodwork now that the political and economic climate is changing. Apparently, they’ve been stored in garages for 15 years. Most striking are the brightly colored VW bugs and a few old Mercedes. Suzuki is in the process of opening up an assembly factory here, because they think the market for motor scooters will boom. Followed (perhaps in 5 years?) by an increased market for small, cheap cars. We ride around in a very funky Russian jeep, with a Toyota to arrive soon.

There seems to be a general consensus that the economy is changing very fast. Russell, who has been here only two months, notices it, and people who’ve been here several years really see the difference. (Some expatriates have been here as much as 10 years.) The expectation is that, if the political will stays firm, this change will continue and accelerate.

I really like our house, although there’s a lot to be done. Basically, we have a bed and a dining table but not much more. However, you can have furniture made in both wood and rattan, and local fabrics are absolutely terrific. I’m going to get started on furnishing the house this Saturday, when I have use of the jeep and Russell’s driver, Kham Khun.

I really like our house, although there’s a lot to be done. Basically, we have a bed and a dining table but not much more. However, you can have furniture made in both wood and rattan, and local fabrics are absolutely terrific. I’m going to get started on furnishing the house this Saturday, when I have use of the jeep and Russell’s driver, Kham Khun.

I don’t yet have a driver’s license, so I have to be chauffeured around. I don’t like being so dependent nor being stuck in an empty house for much of the time, so becoming more mobile is top priority. One way to accomplish this is via bicycle or motor scooter. The vehicles belong to the project, and so, appropriately, project use takes precedence over personal use. Many of the expat women ride bicycles and motor scooters.

When I first arrived, it seemed very hot, but I’ve adapted pretty well in less than a week. Good thing, because the hot season (May-June) is still in front of me. It’s been mostly the contrast with the U.S. winter, I think, rather than an experience of absolute heat and humidity. I will say this, my skin and hair look terrific — all plumped up and youthful.

We’ve joined the Australian Club just down the street, best known for its pool, squash court and other sports facilities. We’ve also joined the Swedish Club, with basketball and tennis courts, as well as a good restaurant.

These two countries have among the biggest foreign presences in Laos. The Americans are not much in evidence, and the diplomats seem to be devoting most of their energy to demanding the bodies of MIAs. This is understandable, but one wonders what kind of remains may be found 20 years after the end of the war. In the meantime, the Japanese, Europeans and Australians are taking advantage of the changing economy and political climate. Will the Americans be left behind once again?

March 16

I’m happy to report that we now have a pretty spiffy set of rattan furniture in the living room. One has the furniture made one place and the cushions another. I’m using traditional patterns of Lao cotton for the cushions. Many people here use European prints, but that seems inappropriate to me aesthetically and economically. Why should I pay to import European designs from Thailand, when I can benefit the local economy and have something culturally appropriate?

We’ve ordered two beds for the guest room, and they should be done in about another week. These will also be covered with Lao cotton bedspreads. The Lao cotton weaving and sewing project is sponsored by the U.N. Development Programme to preserve traditional crafts and provide income for local women which they can earn at home while tending children and other home-bound necessities.

The main source of entertainment is visiting. Since I’m the new kid on the block, we’re inundated with invitations. Last night, we went to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day with an Irish family, who taught all of us Irish dancing. Not content with this, they then asked the different nationalities to teach their dances, so we had Swedish, Breton and American dancing, with yours truly calling a square dance. (“Now the first couple leads down the valley, and they circle to the left and to the right…”) Thank God for my West Virginia roots.

The main source of entertainment is visiting. Since I’m the new kid on the block, we’re inundated with invitations. Last night, we went to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day with an Irish family, who taught all of us Irish dancing. Not content with this, they then asked the different nationalities to teach their dances, so we had Swedish, Breton and American dancing, with yours truly calling a square dance. (“Now the first couple leads down the valley, and they circle to the left and to the right…”) Thank God for my West Virginia roots.

Next weekend, we’re going to take advantage of the one-month vacation in Russell’s contract and travel by ferry across the Mekong to Thailand for a few days. We’ll be able to get some things which are not available here (e.g., cookie sheets and cake pans), as well as do some sightseeing. A famous pre-historic site is near. As one book puts it, “beginning around 4000 BC, a remarkable culture rose and flourished until shortly after the beginning of the Christian era…its people cultivated rice, wove textiles, and made pottery…particularly intriguing to historians is the fact that by around 3000 BC — far earlier than any previous estimates, perhaps as early as anywhere — they had learned to produce some of the world’s first bronze and copper tools…”

March 28

It’s hotter and more humid than normal this time of year. We sweat a lot, shower a lot, drink water a lot, and thank God for air conditioning.

Our ferry trip across the Mekong was definitely an experience! Russell came home from his half-day of work on Saturday (the custom in most developing countries), and after lunch, we drove some 10 miles out of town to the ferry. We weren’t exactly sure where the landing was, but when we got near, we asked a group of people where to find it.

One man was particularly adamant: “It doesn’t run on Saturdays.”

This was pretty disheartening news, but we’ve learned, after 25 years in developing countries, not to give up. “Where’s the landing stage?”

“It’s closed.”

“Yes, but if it were operating, where would it be?”

“Right there.” He pointed to the next opening in the wall that lined the road.

We drove down and were admitted through the barrier. “Is there a ferry running today?”

No answer from anyone because no one spoke English or French, and we don’t have enough Lao yet to ask such questions. We drove through a large, military-looking, deserted compound toward the river. There we found an office with men in uniform.

“Does the ferry go today?” No answer. No English, no French. We could see the road down to the river and a ferry docked below.

We went to another office. “Will there be a ferry today?” No English, no French.

Finally a voice: “Mister, you come here.” Russell went over, and everyone kept smiling and motioning for him to stay.

After a while, a man in uniform appeared, and he spoke some French. “Does the ferry go today?”

“Yes.”

“At what time?”

“4:00.”

“Where can we leave our car?” No answer. Not that much French. Finally, through dint of pantomime, we made him understand. His turn to pantomime: where the car was, parked in front of the first office, was okay.

“Can we get something to drink?”

“Sure. Over there.” Over there turned out to be selling duty-free scotch and gin, not the Pepsis we had in mind.

Back to our French-speaker, now joined by another uniformed French-speaker. “Where can we get a Pepsi?”

“Outside.”

“To the right or to the left?”

“To the left.”

“Is it far? Will we have time?”

“Too far.”

But we decided to risk it. When we got to the barrier dividing the port from the road, the man waved us back. “Pepsi! Pepsi!” we cried.

The universal language: the barrier was opened. There, not 20 meters outside the barrier, to the left, was a shack with a Pepsi sign, and sure enough, cold Pepsis. We bought two for us and two for our French-speaking friends, then back through the barrier with no trouble.

We handed Pepsis to our friends, and we all four sat companionably under the tree and drank this lovely, cold, wet stuff. After a while, one of our friends said, “Why don’t you take the foot ferry?”

“We thought this was the foot ferry.”

“No, this is the car ferry.”

“When does the foot ferry leave?”

“2:30.”

It was now 2:15. “Where’s the foot ferry?”

He pointed downriver. Hurried consultation among the two French-speakers. We jumped into the jeep and rushed toward the barrier, which miraculously opened. Raced down the road. Caught in a religious procession. Finally waved around. Found the parking lot. Paid the attendant 1000 kip (about $1.50) a day to watch our vehicle. Filled out forms, went through Customs, ran out to find a verrrrrrry long flight of steps down to a small flat boat with a roof. Lao scurrying down the steps.

“Is the ferry leaving now?” No English-speakers. No French-speakers either. We sprint down the steps. “Is this the ferry to Nong Khai?” Heads shake yes.

Just as you can’t be sure that no means no, you also can’t be sure yes means yes. We decide to risk it anyway, walking across several moored boats to get to the one on the outside. The young man hits the throttle, we’re all sprayed by river water, and five tense minutes later, we dock in Nong Khai. Now it’s up a loooong flight of stairs to go through Immigration and Customs on the Thai side, but we’ve made it. We’re hot and hassled, but we’ve made it.

“Pepsi?” we inquire.

“Sure. Over there,” says the serene man in uniform. In English. “Welcome to Thailand.”

From the river port of Nong Khai, we took a bus to the provincial capital, Udon Thani, thanks to some help from a Lao refugee who’d fled to the U.S. and was back in S.E. Asia trying to see his family. The Lao hadn’t allowed him to enter, but despite his disappointment, he was still kind enough to help some fellow Americans find the right bus.

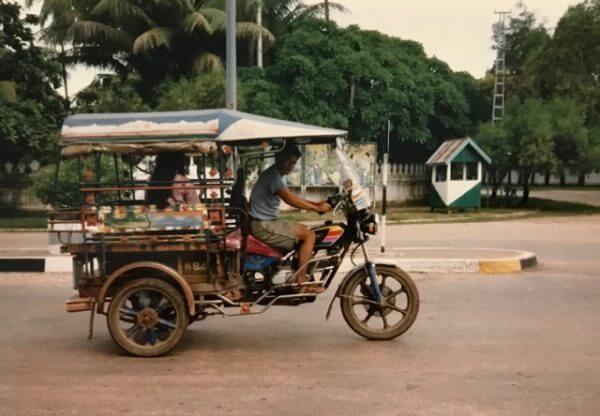

Our bus hurtled along with all windows open and the breeze feeling pretty darn good. Turned out the bus station was outside Udon, but thanks to our refugee friend, we got a tuk-tuk (an open-air, three-wheeled taxi, pro-nounced “took-took”) to the second-best hotel in town.

Our bus hurtled along with all windows open and the breeze feeling pretty darn good. Turned out the bus station was outside Udon, but thanks to our refugee friend, we got a tuk-tuk (an open-air, three-wheeled taxi, pro-nounced “took-took”) to the second-best hotel in town.

“Hello, we have a reservation for a double room with air conditioning.”

“Double room?”

“With a big bed.”

She looked like a teenage chicky-baby recovering from a long night of partying.

“And air conditioning.”

“Air conditioning.”

“Yes, in the name of Sunshine.”

“No room. No big bed. No air conditioning.”

“We have a reservation.”

“Reservation.” She looks it up in a dictionary. The light dawns: we have a language problem here. “No reservation.”

Russell shows her his card. She looks at it with deep concentration and a puzzled frown. We decide maybe the card is too confusing with too much information, so R writes just his name, “Vientiane” and the phone number.

She picks up the phone and starts to dial our number. We’re starting to feel a little frustration. “Thursday, we called Thursday and made a reservation.”

“No reservation!” She’s getting a little testy.

I ask to go behind the counter to the calendar. She agrees. I point to Thursday and mime a telephone call from the north to the hotel and keep saying, “Reservation, reservation.”

She flips over her reservation book (To Thursday? We’ll never know.) And there, big as life, so big I can read it across the room, it says “Russell Sunshine” with some Thai words after it.

“Ohhhhhhh,” she says. No apology. No indication of a goof, but we get the penthouse on the roof with sitting room, bath, double bed and air conditioning. It may not be as spiffy as the number-one hotel, but it’s home for three days, it’s $10 a night, and it’s cool.

The rest of the trip went pretty much as planned. We hired a taxi and visited the prehistoric site. Very interesting, with the museum captions in both Thai and English. The workmanship in pottery, metal and jewelry was very fine. I saw several necklaces I’d be happy to wear today. Too bad they don’t sell copies in the museum shop.

The return was basically uneventful. We went by taxi back to Nong Khai, because we had to carry all the fruits of our shopping. We now knew the ferry drill, so that was easier. The jeep was still there, and we bought some melons on the way home.

It was a good trip. We had a good time. We have stories to tell, and we know how to do it the next time.

COMING NEXT MONTH

Laos, 1991-1993: Flora and Fauna

Three cats, a gibbon, a family of lizards and the garden where they lived

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.