#15: Guest Contributors

The 1990s brought big changes to my life overseas. Before we explore that transition, I thought it might be interesting to hear from others who’ve lived and worked abroad. Not counting the military, 8.7 million Americans currently live in over 160 countries. If they all lived in one U.S. state, it would be the 12th most populous — right between New Jersey and Virginia. You may have friends or neighbors who’ve lived that life. They all have engaging stories to tell. Here are true tales from a few of our friends:

Fern Gruszka: Tanzania, 1972

Fern is one of many women I was privileged to meet while living overseas. Born Fernanda Pozza and raised in northern Italy, she emigrated to Canada with her family in the 1950s. She and husband John spent five years in Tanzania. Fern continued volunteering on development projects for 30 years as an educator, project reviewer and fund-raiser. Concurrently, she worked as a Systems Analyst and Manager in Canadian government agencies. They now escape the cold Canadian winters to their home in Mexico.

During our Volunteer days in Dar es Salaam [capital of Tanzania], we bought an 11 year-old Ford Taurus, as we lived 20 kms. [about 12.5 mi.] away from my work. This vehicle had been on the coast its entire life and not well-treated, but we thought we could take a camping safari to the game parks for an affordable volunteers’ holiday.

We missed our Tarangire Park turnoff and about 30 miles on, the vehicle overheated badly. All the water had leaked out of the rusted radiator. Within minutes we were surrounded by locals appearing out of the bush. With broken Swahili, we requested water. One fellow indicated a stream just nearby. I took our jerry can and followed him while John stayed with the loaded car. An hour’s walk later, we reached the stream, filled the can with a coconut shell and headed back. I could barely lift the can. The young man picked it up, put it on his head, and we walked another hour back. JOHN WAS RELIEVED TO SEE ME. We re-filled the radiator and set off.

Within an hour the water was all gone again. We decided to abandon the safari and go back to Arusha. Found a duka [shop] that had (amazingly) some radiator sealant. Got more water and put it in. When we started the car, the sealant came flying out of the radiator and onto the windshield. Travelled about half an hour and stopped at a village for water. The central tap was barely dribbling, and there was a queue of ladies waiting their turn. We also lined up. Shortly afterwards, the village leader approached us. Our best greetings and explanations were exchanged. He proceeded to order all the ladies away and had them fill our jerry can with their water. We offered money, but he refused, and we were again on our way.

About 5:00 p.m., we were stuck again on the paved part of the road with no water. A car approached. It was a Greek farmer who had been in Tanzania many years. He asked if we had any bread. We were camping and had plenty. He took a loaf and, with some water he had in his vehicle, made a dough. He then filled a large portion of the radiator on both sides with that, leaving the not-so-rusted edges clear. He told us to let the dough bake by running the car and then drive very slowly back to Arusha. It worked.

By this time, it was dark, and we hadn’t had anything to eat since breakfast. We stopped and made some tea in the pitch black. Suddenly two Masai appeared out of the dark — armed with knives and spears as always. The two warriors tried to engage us in conversation, but their Swahili was almost as bad as ours. We offered them tea, with some trepidation. They declined and shortly left. We made it back to Arusha and had to wait 12 days for a radiator to come from Nairobi. That was our holiday allotment for the year, so we headed back to Dar and work. A memorable first safari. Fortunately, we were in Tanzania for 5 years and made many subsequent, successful and unforgettable trips.

Jane Shetler Ross: Sri Lanka, 1974

As noted in previous posts, I owe my husband to WVU friend Jane Shetler, who introduced us many decades ago. Jane met and married Richard Ross in Calcutta where she was working as a volunteer for the World YWCA. They lived abroad for 25 years in Colombo, Kabul, Paris, Rabat, Sana’a, and Damascus. Now retired in Washington DC, they travel overseas for several months a year.

I accompanied Richard to Colombo, Sri Lanka, where he was Cultural Affairs Officer at the US Embassy. Before long, I was suffering from trailing-spouse syndrome.

Our Sinhala teacher introduced us to Lester James Peries, the “father of Sinhala cinema,” and his wife Sumitra, also a film director. Sensing my boredom, Lester asked if I wanted to type the shooting script for a Sri Lankan-British production he would soon direct. My high school typing was perfect for the ancient Royal at the film offices. When I finished the script, Lester invited me to accompany them on location at Sigiriya, a massive rock 200 meters high in central Sri Lanka.

The story of “The God King” is set in both Sigiriya and Anuradhapura, an ancient capital of Buddhist temples, both now World Heritage sites. In 400 AD, bastard son Kasapa declares himself king, deposing his father and walling him into the fortress he was building on Sigiriya. The rightful heir challenges the usurper, and a complicated struggle ensues, ending as Kasapa kills himself in a great battle.

Our cast and crew occupied quarters in a spartan government Rest House. I was assigned to wardrobe, which involved getting actors and animals dressed. Daily we climbed to the top of Sigiriya by a steep rocky path and iron steps, gripping the old rails that kept us from falling.

In late afternoon, sunburnt and exhausted from working outdoors with little shade, we climbed back down. Once showered, we were ready for Ceylon cocktail hour – local gin, beer, arak, or ginger beer. We ate a late rice-and-curry dinner while the old hands shared tales of previous films, and I listened. The jungle’s peace and quiet lulled us asleep.

After weeks of shooting, we were to move to Anuradhapura for scenes in a “palace” set. But financing fell apart, and talk of a curse on the film by a famous monk became a rationale for stopping. British actors and staff returned to England. We returned to Colombo. After some weeks, the financial situation was resolved, and we were called back with three new leads and the UK production staff.

In Anuradhapura, the wardrobe mistress walked off the set. Suddenly I was in charge of costumes. First call was dressing horses and elephants with elegant jewelry and regal trappings; second call was minor characters, warriors and crowd scene extras; third and last were the principals. Asian elephants traditionally demand spending part of their day in a stream. Noontime seemed the inflexible limit of their patience. One day the filming went too long, and an elephant in complete regalia charged off to soak, his mahout (trainer) in fast pursuit. We lost the entire costume and jewelry.

The shooting eventually moved to studio sets in Colombo. When filming and post-production ended, I found myself in a darkened theatre for the Asian premier, reflecting on the amazing opportunity to meet, work and live with Sri Lankans so early in my stay in their country. Richard and I were in Sri Lanka for four years. Many of my friends on the film became valued contacts in his cultural work.

After decades of being a dependent spouse, I joined the Foreign Service in 1992, later returning to Colombo as the Management Officer at the American Embassy. Some 30 years after we’d first left Sri Lanka, we joyfully renewed friendships forged with Lester, Sumitra, and many in the film crew.

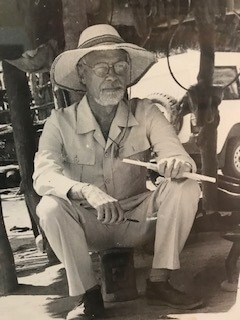

Gary Davis: Ghana, 1979

We met Gary Davis in East Africa during postings which coincided, ending in 1975. Gary set out to be a San Francisco lawyer but was subverted by a Ford Foundation Fellowship into a 30-year career in international development, nearly all of it south of the Sahara. Retiring in 1998 as the head of United Nations operations in Zambia, he took both daughters on epic ocean canoe trips in Alaska, a lifelong passion.

If the unusual shift in the sound of the jet engine did not fully awaken me, the explosions and machine-gun fire a few moments later certainly did. Our bungalow on 3rd Cantonments Road was beneath the approach path to the Accra Airport, so we were accustomed to the sound of aircraft, but not to the alarming sounds of the start of civil war.

It was just dawn on the fourth day of our daughter Vanessa’s life. She’d been born in the evening three nights before at a local hospital, and I’d brought her and her mother, Edith, home promptly the next morning to avoid prolonging their stay in the under-equipped facility. Edith was not only young and in good health, but a trained midwife and brave, so we had been confident in coming home so swiftly, a corner of our bedroom serving as our newborn’s nursery.

Our other daughter, Kirsten, was two and sound asleep in a separate part of our airy screened bungalow — her room a former “walk-in closet,” which unlike all the other rooms, had the advantage of four solid walls.

We were in Accra with the United Nations Development Programme, providing aid to strengthen Ghana’s socio/economic development. While the country today is looked upon as a model for good governance and development in West Africa, it is not an exaggeration to say that it was a terrible mess in 1979.

As the UNDP Deputy Resident Representative and the officer who lived closest to where the coup was happening, I felt an immediate responsibility to do what I could to raise the alarm. There was no functioning phone service, and we had no walkie-talkies, so within a minute I was in my car, clothes pulled over pajamas, rushing across town to alert the Resident Representative and to go to our office to stop the drivers from bringing our local staff to work.

I had difficulty with the first task since my boss lived in a house with solid walls, and everyone was asleep with air conditioners blasting. I finally woke one of his children by throwing rocks against her 2nd story window. But I failed in my second task, since the senior Ghanaian driver, who arrived at the office after I left and evidently felt he knew better, overrode my order, with the result that the staff was brought in to our building next door to the Police Headquarters where their lives were endangered by heavy fighting for two days.

By the time I started back, the streets in our neighborhood were full of soldiers and armored cars. I felt lucky to reach home safely. By nightfall the situation became terrifying with machine-gun fire nearby, and daughter Vanessa spending her fourth night on Earth in her mother’s arms while we hunkered down with a bottle of brandy in a back hallway with solid walls.

Clearly we made it, but…I think I know why Vanessa has always been a bit of a rebel, and why Kirsten sleeps so soundly!

Cynthia Beach Guthrie: Paris, 1980

Even after retiring from international life, we keep meeting folks who also lived overseas. Like our friends, the Guthries, fellow members of Central Coast Writers. Cynthia Guthrie is a lifelong nomad, who while living in 11 states & 6 foreign countries, grew up, married, acted in community theatre, taught English as a Second Language and raised a family “on the road.” She’s writing memoir vignettes that she plans to put in a collection called A Family of Warriors, Some of Whom are Soldiers.

Back in the 50’s when we were courting, Dick promised he’d take me to Paris one day. I dreamed of drinking wine on the Left Bank while discussing philosophy with Sartre. I arrived in Europe for the first time two decades later, in 1969, a year after Dick returned from Vietnam. I had a six-week old infant on one hip and a nineteen-month old on the other. Even with babies, I learned to love France and adored Paris.

In 1980, coming out of commanding an Infantry Battalion at Ft. Stewart, Georgia, Dick received orders to attend the French Ecole Supérieur de Guerre. We were moving back to Paris!

This time, I wanted to live in the heart of Paris. And we did: in the 8th arrondissement, a half block from the Seine, two blocks from the Champs Élysées. Those babies, now ages eleven and twelve, and I jumped on the Métro to go to the Alliance Francaise to study French while Dick joined the Ecole Supérieur de Guerre as the American exchange officer. Laura and Park had attended six schools in five states. In the fall, they adapted to their seventh. I learned to “keep house” the Parisian way and studied for a certificate in teaching English (TESOL). I strolled the avenues and “breathed in” the City of Light.

On Sundays, we walked to the American Cathedral of Paris on Avenue George V. We’d eat millefeuilles from our neighborhood pâtisserie or drink café au lait at our favorite sidewalk cafe. We all reveled in living in Paris.

In January 1982, everything changed. A US Defense Attache was shot in the head as he got into his car in front of the apartment where he lived with his wife and two teenagers. After being alerted of the murder, I galloped the three blocks to where the kids would be getting off their school bus. I wanted to make sure that not even for one second would they think the US Army Lieutenant Colonel who had been assassinated was their father. The next day, a different US Army officer, who lived in our building, was escorted to work by armed guards in an armored car. He left through the same door, the only entrance or exit to 11 Rue Bayard that we all used. Not being assigned to the US Embassy, Dick was not authorized the same protection, so he asked for permission to carry a weapon. For our remaining months in Paris, Dick never ventured outside without the snub-nosed .38 caliber revolver strapped to his body.

We took precautions and life went on. Both kids performed in their school’s production of “Fiddler on the Roof,” I taught English to adults, Laura graduated from 8th grade, and Dick finished his course. As we drove away to a new assignment in the Netherlands, I knew I was leaving my favorite city in the world. For better or worse, my beloved Paris and I wept.

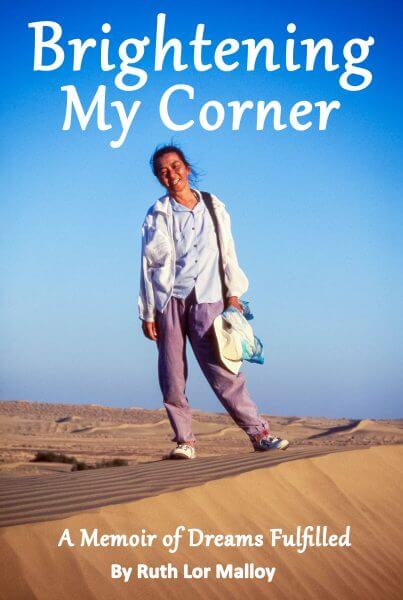

Ruth Lor Malloy: India, 1995-97

I met Ruth in Almaty, Kazakhstan, when we worked together to produce a guide to help expats function in this newly-separated member of the former Soviet Union. She later accompanied her husband Mike to India, where he worked for DOW-Jones, setting up a business news bureau with an Indian company. The following story is abridged from two chapters in Brightening My World, a Memoir of Dreams Fulfilled, available in 2022. Ruth is the author of a dozen travel guides to China and helped ghost-write a successful book about the transgender Hijras in Mumbai, India.

I saw my first Hijra at a stoplight walking from car to car, begging, a scowl on his movie-star handsome face. A woman in the car ahead rolled up her window and turned away. Wearing a white sari decorated with flowers, he had long hair, clasped at the nape of the neck. His movements were more masculine than feminine. Was this some kind of college initiation? A joke? I kept seeing more men in women’s saris as I explored Mumbai and asked our driver who they were.

“Bad,” said Ashok. “Hijra. No good.” He pronounced it “Hij-ra.”

What had they done to deserve such treatment, I wondered. India was a male chauvinist country, sons preferred to daughters. To see men in women’s dress was bewildering. Who were they? Why were they wearing women’s clothes? Why did people hate them? Were they criminals?

“They’re dirty,” said one woman. “I can’t stand them touching me.”

Said another, “If they get angry at you, they lift up their skirts and show you… I hate them.”

“Hijra means Third Sex, neither man nor woman,” explained a police commissioner. “In English, they’re called Eunuchs.”

I learned later that the word “Hijra” is derogatory. It was a term they used themselves, so I have continued to use it here with apologies.

Social worker Anaxi said 90% of the Hijras were victims of kidnapping. They were children from poor families who were taken to Hijras to be castrated.

I think my jaw must have fallen open at her description. “That’s terrible,” I gasped. At the same time, I wondered if they needed help.

“They make money by blessing newborn babies,” Anaxi continued. “It’s considered good luck for newborns to be blessed by Hijras, or conversely, not to be cursed by them. So parents give Hijras a thousand rupees [c. US $14] to sing a song. They’re invited to bless marriages too.”

Some days later, we visited a small Hijra colony, a couple shacks behind the Mahim railway station. Two Hijras appeared as we approached.

“Refer to them as ‘she’ and ‘her,'” advised Anaxi. She introduced us and explained we were social workers who wanted to know more about them. The Hijras invited us into their group’s hut of straw mats and plastic sheeting. Since the weather was hot, the bottom of the walls was rolled up to catch the occasional breeze. Through this opening, I could see railway tracks a few feet away. The room was clean but cluttered with wooden or straw partitions and clothes hanging on lines. No electric wires or light bulbs. A small shrine with two goddesses was on the floor.

The Hijras wore clean, decent-looking saris. One was about 4 years old and like the rest, decorated with a necklace, earrings, and bangles. Some of their faces were unquestionably male and angular; the rest, androgynous. A couple showed traces of beards. They said they were women in every way except for bearing children. Their names were female: Sumitra, Baby Dancer, Rita, Priya. They felt like women, and wanted to be women.

Meena Balaji was a big woman, obviously a leader. She wore gold earrings, a nose stud, bangles, and a dowdy green house dress. She said her “family” consisted of 14 Hijras. We sat on the floor as Meena dominated the conversation with her strong voice and expressive hands, seeming to enjoy our attention.

Meena said she spoke several languages besides English and had completed one year of a B.S. degree. She’d dressed female since she was a child. At ten, she realized she was different and decided to leave home at 16. Tears filled her eyes as she talked. She was an embarrassment to her parents. She’d had an operation, paying a doctor about 15,000 rupees [c. US $205].

“Many people come to talk to us,” she said. “We see their stories in the newspapers, but that’s the end of it. Journalists tell lies about us. They promise to help us get jobs but never do.” We didn’t tell her until later that I was a writer, but it was true: many journalists publish a story and then do nothing more. I wanted to show them that some journalists really cared. I was also curious to find the truth in what they were saying.

So began the partnership which produced the book Hijras: Who We Are by Meena Ba

Do you have an engaging story to tell from your own experience living and working overseas? If so, please contact me via nancy@nancyswing.com, and I’ll send you some guidelines (e.g., word-length, etc.). I’ll post more of these true tales when I get enough to fill another monthly blog.

COMING NEXT MONTH

Laos: Trying to be a Dependent Spouse

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.