#11: The 1980s — Here, There and Everywhere

The 1980 project in Somalia was the first of multiple short-term assignments in developing countries during that decade. I went a second time to Somalia, at least five times to Pakistan and once each to Jamaica, The Philippines, Guyana, Egypt and Kenya.

Pakistan

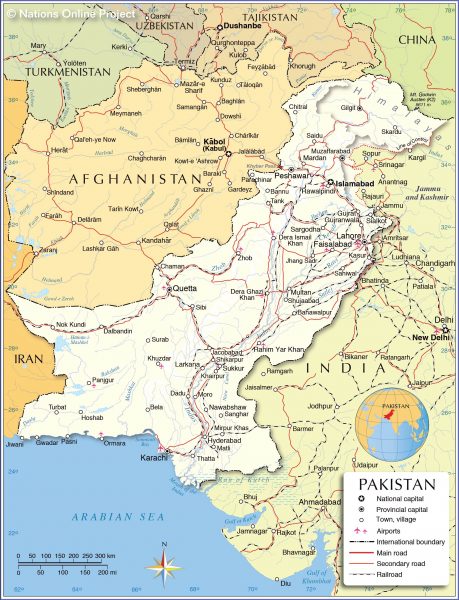

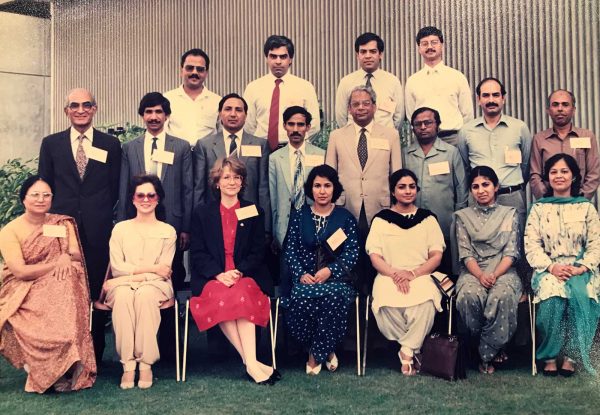

Unfortunately, all the journals from my various projects in Pakistan are not to be found anywhere. The only artifacts are a few photos, mostly official pictures of the groups I worked with. Consequently, I’m not even sure of the number of times I went there; it may have been as many as seven. All were under the auspices of the USAID Management Training Project. My role was as a single consultant hired by the main contractor to conduct mostly “training-of-trainers” in a variety of settings — Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore, and Swat. I also traveled to Quetta as part of a needs assessment team with my Pakistani female counterpart. I feel blessed to have seen so much of a country that has been at the crossroads of history for millennia.

Research shows that one of the best indicators of who’ll be successful working in other countries is the ability to deal with ambiguity. Most of us carry cultural baggage from our own upbringing with the result that what appears crystal clear to those raised in a host culture may be ambiguous to us. We may misinterpret actions or be totally baffled about what they mean.

As we learn to live and work successfully in another culture, we may also realize we’re feeling ambivalent. We find ourselves being of two minds about experiences. We may come to understand, and even appreciate, a lot of what was initially disconcerting in the host country. But we still carry our own values, customs and mores. These contradictory insights can nurture ambivalence. A memory from my days in Pakistan may help illustrate the point.

I’d worked off and on for some years in Pakistan and felt comfortable, even at home there. But an incident helped me realize how ambivalent my reactions could be. One afternoon, I was walking from my guest house to the nearby shopping street, wearing not only the baggy pants and tunic of the culture, but also the dupatta, a scarf draped across the chest, obscuring one’s bosom so as not to inflame male  observers. As I strolled along, enjoying the sights and sounds, a motor bike with two teenage boys whizzed by. Just as they passed, I realized that every private place on my body had been tapped, front and back. Of course I felt violated and outraged, but part of me was filled with wonder at the dexterity of their actions. How did they manage to do that? Did they each concentrate on different parts of the anatomy? How did they coordinate this complicated choreography on a speeding motor bike?

observers. As I strolled along, enjoying the sights and sounds, a motor bike with two teenage boys whizzed by. Just as they passed, I realized that every private place on my body had been tapped, front and back. Of course I felt violated and outraged, but part of me was filled with wonder at the dexterity of their actions. How did they manage to do that? Did they each concentrate on different parts of the anatomy? How did they coordinate this complicated choreography on a speeding motor bike?

When we were together later that day, I told my Pakistani counterpart, a woman who was like my sister, what had happened. Shahnaz said a number of neighborhood women had been assaulted in this manner, but this was the first time it had happened to a foreigner. The police had been notified before my experience, and male Pakistani neighbors were on the lookout for the boys.

The next day at the training site, one of the participants came up to me during the morning break. Tall, with dark eyes and long hair, he was the physical epitome of his Pathan tribe, famous throughout history as fierce fighters. “My sister,” he said, “I heard what happened.” Carefully blocking the view of others, he showed me a huge knife. “I will punish them for you.”

Yes, I’m thinking, it was bad, but not that bad. And I’m feeling touched that he cares about his trainer’s honor. Meanwhile wondering how I can prevent bloodshed.

I managed to express my gratitude without encouragement, saying we should wait to see what the authorities might accomplish. He seemed kind of disappointed. The authorities didn’t do much, but the Pakistani vigilantes caught the two boys, who turned out to be neighborhood residents, and gave them a severe beating. No one — not the boys, not their parents nor extended family — complained to the police. A local, modern problem had been solved locally and traditionally, and that was the end of it.

Ambivalence from beginning to end — from the boys on the bike, through the Pathan’s offer, to the neighborhood vigilantes. An American in Pakistan.

The boys on the bike were my only unpleasant incident with Pakistani males. Over some seven years working off-and-on there, most of my memories remain happy ones. Like the night I went with Shahnaz’s family to watch sea turtles lay their eggs. In the eerie light of our escort’s kerosene lamp, great seafoam-green creatures deposited scores of eggs, weeping copiously from the sand’s irritation.

Being with them feels like a sacred experience. The eggs emerge from the mother like soft ping-pong balls, slightly elongated from their passage but soon becoming round. When she’s completed her cache, she uses her hind flippers to cover the nest and then moves a little away to flick dry sand on top to further camouflage her labors. Once finished, she levers her ungainly body back to the sea, seemingly forgetting her brood and only returning next year when she deposits another cache. In about two months, the baby turtles hatch underground, taking 5-7 days to dig their way to the surface. Both the laying and the hatching of eggs usually occur in the dark of night, thus helping to ensure the survival of some eggs and some hatchlings.

More happy memories: Times spent with the extended family of Rukhsana, one of the course participants. Especially the remarkable women. The gracious aunt who made a lemon meringue pie when she learned it was my favorite. And Rukhsana’s mother, wife of a diplomat and one inspiration for the character Anjali in my first book, Malice on the Mekong. I had the pleasure of recommending Rukhsana for a scholarship to study for a Master’s degree at The American University’s School of International Service. When she graduated, I put on my cap, gown and doctoral hood to march with the rest of the faculty in honor of her achievement.

Last but not least, all the social events. Dinner with male participants, as they took turns reciting lines from Persian and Urdu poetry to commemorate the occasion. Those that were especially apt were greeted with the raised hands of fellow diners and a breathy explosion of “Wah!” Or the party of all-female participants at the end of a course aimed at empowering women. Singing and dancing without the inhibitions posed by male presence. And the weddings, especially the challenge of approaching the bride and groom after the ceremony to offer a traditional sign of good luck — cracking all the knuckles of both hands against the sides of my face. Terrified I’d fail, not flexing or massaging my hands for days so all ten fingers would resound with ten quick clicks. Hosanna! Got it every time.

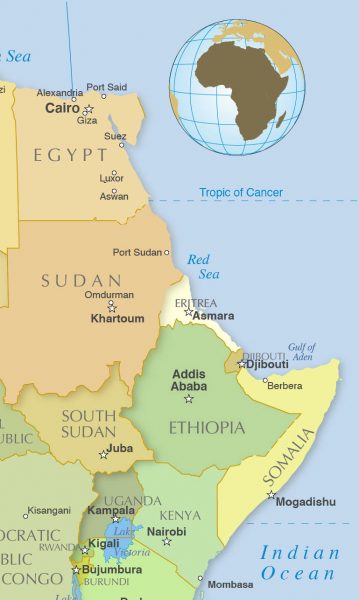

Nairobi and Cairo, 1982

I was hired by a department of the World Bank to help them improve their seminars on Bank guidelines designed to ensure borrower countries’ responsible use of international development funding. These in-country seminars featured lectures and case studies with the Third World participants being mostly passive. The Bank department head had data showing that once the Third World officials returned to their posts, they were still having difficulty following the guidelines. So I accompanied the trainers to observe their seminars in Nairobi and Cairo. (To protect their privacy, I’ll call them Trainer #1 and #2.)

It was a challenging task. First, how to make fairly dry content — understanding and implementing guidelines, filling out forms, etc. — engaging. Secondly, you might imagine how my assignment could be intimidating to the two men who’d been conducting those seminars for years. Finally, working for the World Bank offered its own trials for a woman who preferred working close to the grassroots. Yet I was intrigued by these challenges and decided to take them on, keeping a journal of events and my reactions.

May 24

Nairobi’s changed a lot since I first came to East Africa a decade ago: many more fancy high-rise buildings, including the new Kenyatta Hospital coming on the hill near the old East African Community buildings. No longer an African city, it’s now very cosmopolitan. Hard to discern the city’s origins. I miss those low buildings of native stone and red-tiled roofs.

Most of the Bank staff here are high-handed and contemptuous, even xenophobic toward Kenyans and Third Worlders in general. Both trainers think Africa won’t make it. How can one have these attitudes and be an international civil servant in development?

Trainer #1 is good at lecturing, #2 at conducting case studies, but they both do both. The best lecturer’s flipchart is better than I’d been led to believe. Identified a number of A-V aids which could be helpful to illustrate all this verbiage. Will hold off on recommendations until I observe Cairo seminar and return to DC.

May 26

Meeting tomorrow with three of my five Kenyan graduates from the DC-based Ag. Communications course. Two of them are upcountry, but the three who are in Nairobi will come by for a drink after work.

May 27

Saw two of the Kenya grads. Great to be with them and hear their enthusiastic reports about the value of the Ag Comm course once they got back home. The third grad was busy organizing an exhibition at Kenyatta Conf. Center, which I’ll visit tomorrow. How I wish I had more time to go with everyone around the country and see what they’re doing.

Sitting through these World Bank seminars is a boring way to make money. I’m not jazzed about doing another project like this. Also feel uncomfortable staying in our luxurious hotel, being entertained by Bank and Government elites at fancy events, etc. This doesn’t feel like development (although it is, just at the macro-level?).

May 28

May 28

Realized today I’ve seen the closing of an era in East Africa. I’ve witnessed a major transition. Years from now, when they identify this period of history, I will have been a witness.

Of course it hasn’t reached all of East Africa, but it’s growing at an exponential rate. Nairobi’s become a vertical city with shops full of goods we could only have dreamed of in the ’70s. Hunting is now banned in Kenya, and people speak matter-of-factly about the eventual complete disappearance of game. Most of the authentic things are gone from African Heritage. Almost no one in traditional dress. A symbol — young Kenyan women with elaborate, cascading braids: Western interpretation of African style transplanted back to Africa, false braids, gold threads and all.

May 29

Got a prescription for my mild conjunctivitis and stopped at the Thorn Tree for a sweet roll and hot chocolate. Met a Brit who’s in charge of oil-drilling camp off Tanzanian coast. We talked of safaris we’ve made, and our conversation reinforced how much I want to stay in grassroots work. This assignment is too easy and too far removed from where it’s at. Please, God, send me back to the bush.

May 30

Flew to Cairo via Addis Ababa and Khartoum. As the plane left Addis, we banked very sharply through a bumpy layer of alto-cumulus. “What the hell’s he doing?” I asked myself. Then I saw mountains higher than we were, just off the wing tip. And they were green with fields at well above 8000 feet. From before Khartoum to Cairo, there’s nothing but barren land, golden in color, sometimes flat, sometimes ridged, sometimes dune’d, sometimes wadi’d. For as far as the eye can see from a five mile-high plane, there’s only desert for three hours. Awesome.

We were met at the airport by Shereif, Egyptian official delegated to look after us. I found myself gazing at the city rushing by and feeling very glad to return [after our previous visit on the way home from E. Africa]. I think I’d like to live in Cairo for a couple years, even if it would wreck my skin.

I have lots of problems traveling with the World Bank. Fanciest hotel I’ve ever stayed in — très, très posh. Marble everywhere and balcony with a view up the Nile. More closet space than in our whole house. On the way from the airport, the trainers were sitting in the back of a vehicle driven by an Egyptian and escorted by an Egyptian official while commenting contemptuously on Egyptian procedures, confusion, “chaos,” and inefficiency. I wanted to move to the front and sit with the good guys.

As I stand on my balcony and watch the sun turn beige Cairo to gold and neon jewels start to glow, I am glad to be back, even if it is with the World Bank.

May 31

Found Trainer #1 going through my notes while I was in the ladies room. Because my client is their boss and I’m submitting my recommendations to him, I’d repeatedly resisted #1’s efforts to pump me about my observations. So he took advantage of my bathroom break to search my portfolio. He really had to go out of his way to get it, because I was sitting at the back of the room in a corner, far from the traffic pattern. When I caught him reading, he smirked and said, “Very interesting.” I’ll of course take care from now on, but I’m wondering if I should report this to his boss. That decision later…when I’ve calmed down.

The Ministry’s classroom is a disaster: windows open to catch breeze, noisy traffic on two sides, bad visibility, etc. I went to see about a better training space at our hotel. Accomplished via multiple cups of mint tea, diverse conversation before getting down to business, etc. We’ll move there tomorrow.

June 2

Yesterday felt so awful, I decided not to relive it by writing it down at the end of the day. I still don’t feel like reliving the worst of it, but I have the obligation to record.

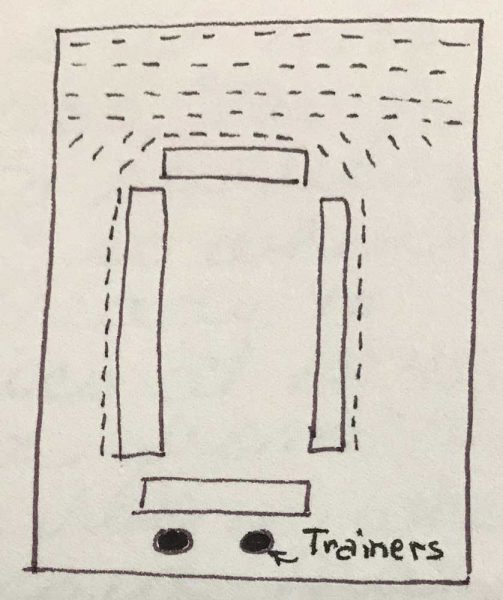

As we had agreed, the hotel had set up our training room in auditorium style, because we had 70 participants to fit into limited space. The trainers changed the configuration to 35 chairs around a U-shaped table. 70 people showed up, just like they did the day before, and we had to cram in another 35 chairs at the back of the room, with the result being something like this ———>

As we had agreed, the hotel had set up our training room in auditorium style, because we had 70 participants to fit into limited space. The trainers changed the configuration to 35 chairs around a U-shaped table. 70 people showed up, just like they did the day before, and we had to cram in another 35 chairs at the back of the room, with the result being something like this ———>

Claustrophobic and hot at the back. People couldn’t hear well or read the flipchart, the blackboard or the transparencies. #1 then lectured for 2.5 hours. The original seminar schedule had been from 9-2, sans lunch and with two breaks, according to local custom. The trainers decided to pay for only one serving of coffee/tea, so they cut the breaks down to one, at 11:30 instead of two at 10:30 and 12:30. By 10:30, the participants were getting restless and inattentive, so when #1 was ready to change topics at 10:45, I suggested from where I was trapped at the back of the room that perhaps we might take a very short break to stand and stretch. This was met enthusiastically by the Egyptians, but #1 vetoed it. Everyone stood up anyway.

Many Ps came up to me when we finally got a break to thank me for my effort on their behalf. Then #1 and I discussed the need for breaks, but he again refused.

Near the end of the second session, #1 tried to lead case studies, but the people at the back of the room wouldn’t/couldn’t play. He continued the case study with the 20 or so Ps near the front. When he finally released everyone at 2:00, some had already left, and others were very disgruntled.

#2 and I went to lunch while #1 ate with a compatriot currently working in Cairo. I tried, with some finesse I thought, to raise some of the day’s issues with #2. He replied he was well aware of the attention curve of adult learners, but he frankly had no sympathy for them. Let them learn some self-discipline. Class is class, and if 40 year-old civil servants can’t sit still for 2.5 hours, that’s their hard luck. As for all the people crowded at the back, that’ll teach ’em to come on time.

One of the most disheartening conversations of my life. No wonder the World Bank guidelines aren’t being followed when seminar participants are placed at such learning disadvantages by care-less trainers. I don’t know how to relate to such callow arrogance.

Shereif and driver came for us in the late afternoon. He’s apparently been assigned to ensure we experience some of what the area has to offer, so he first took us to a village famed for its handicrafts and then on a circuit of the pyramids at sunset. Throughout, #1 kept trying to get out of a dinner invitation from a Ministry Undersecretary. #2 finally got quite sharp and said protocol demanded that he go. Even then, #1 argued, “You and Nancy are going. It is enough.”

At the pyramids, I had a long conversation with a man who gives tourists camel rides and promised to return, Inshallah, for a ride on Friday. He handed me his card: “Teacher of Horses & Camels.” Does he train horses and camels or teach people to ride them?????

Lovely dinner at Al Adin (“Aladdin” to English-speakers) with several Undersecretaries. Very pleasant conversation, full of courtly compliments and gaiety. Then one of the Undersecretaries took us on a personally driven night tour of Cairo.

I very much enjoyed the later events of yesterday and had occasion to reflect that I’m here to win the war, not one day’s battle.

Tried to stay detached about today’s seminar by leaving every hour for a few minutes. The same counterproductive trainer behavior was going on,; e.g., #1 agreed to two breaks but then gave the participants only one. I decided it’ll all be in the report for their boss to decide what to do.

June 3

The last class wasn’t bad. We ended at 1:00 with speeches and a gift for me from one of the lady participants. Shereif brought me a set of silver prayer beads from Saudi Arabia and a tiny folding address book. I was really overwhelmed and will have to do some serious shopping for him and his family (whom I’ve met) when I get back home.

June 4

June 4

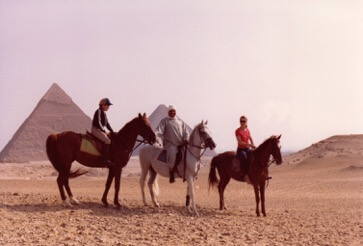

Friday, so day free. Up at 6:00 and off at 6:30 with American friends who’ve been living/working here for a couple years. Rode near the pyramids in the early morning with Dad and older son. I’m out of practice sitting a horse above a walk. Despite raw inner knees and what will surely be sore joints tomorrow, I had a marvelous time. Sadly, the Teacher of Horses and Camels wasn’t in evidence, so no camel ride.

Afterwards, we riders joined Mom and younger son for lunch and sightseeing. They’ve decided to stay in Cairo so Dad can practice law with a local firm. We visited the traditional Egyptian house they’re buying in Maadi. Drove through the City of the Dead (miles of modern-era tombs) and past the back of Saladin’s Citadel to Khan El Khalili bazaar, where we just wandered here and there. You don’t have to buy things to have a good time. Dinner in Giza at a typical Egyptian outdoor restaurant — 10 appetizers plus rice and lamb with two kinds of wine — awfully greasy, but authentic, and we all loved it.

The World Bank trainers and I started home early the next morning, with an overnight in London, where I got to see English friends from East Africa days. Once back in DC, I wrote my report detailing what I’d observed, good and bad. My recommendations included that the trainers attend a workshop on facilitating adult education, although I feared they were too set in their ways to profit from the course. I vowed to myself that I would never again accept this kind of assignment. Nothing about the professional experience was worth it.

COMING IN APRIL

Back to Somalia: Bao, Khat and Black Mambas

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU: nancy@nancyswing.com

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.