#10: Somalia 1980, Part 2

People often ask me what’s my favorite country. Surely one of them is Somalia. These people who have had to endure so many trials are tough and yet gentle, hardened and yet gracious. My days among them were blessed with support and lessons in how to face life’s demands. Let’s continue the story of that first sojourn with excerpts from my journal.

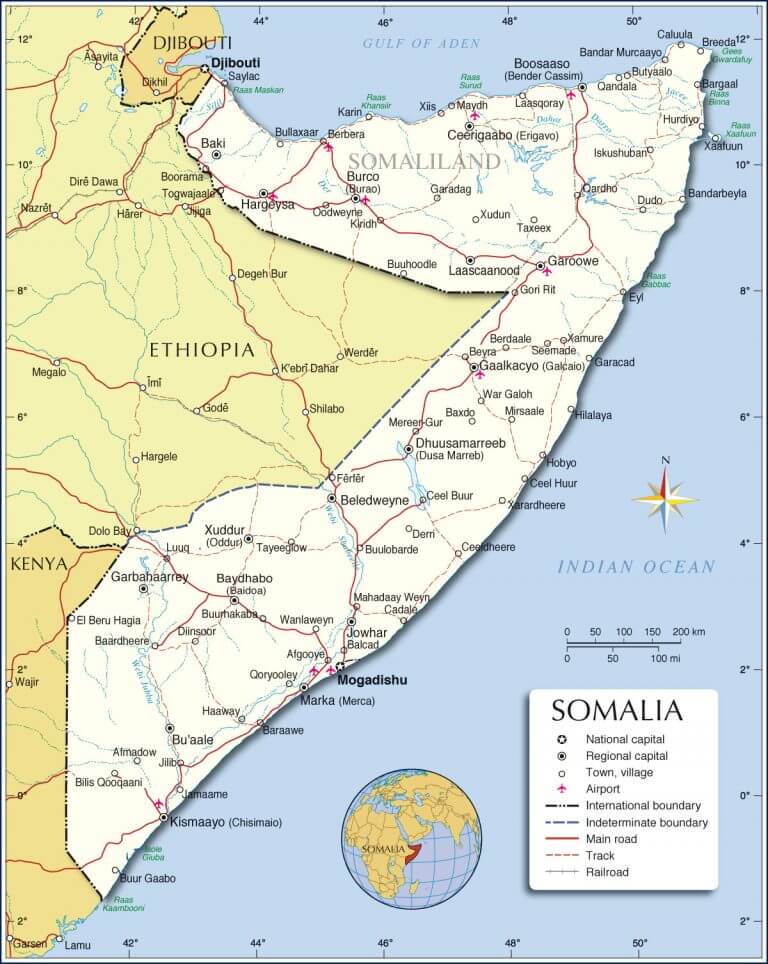

Baidoa [Baydhabo on map]

March 12

Everyday, when the 4:00 session is due to begin, the participants are becoming increasingly lax about showing up on time. About half are punctual, but the rest drift in one-by-one. Because most of the training involves small group cooperation, it’s almost impossible to get things going until everyone is present.

Today, things came to a head. After we’d waited for some time after the “bell” had been rung (a rock pounded on the flag pole), and I’d inquired where everyone was (a pattern which had been repeated for several days), I threw a fit, only half of it faked. I grabbed the box of course materials, turned to those who were there and said something about if others didn’t care about learning, I didn’t care about teaching. Then I stormed out, G following a few seconds behind.

Explosion of Somali voices heard all the way across the compound and into our “office” where G and I were discussing the morning’s exercises. After a while, Hawa, the only woman participant, came to get us saying, “They will never again come late.”

G and I went back to class, where I said something like, “It’s your course, not ours. You are the extension agents, not us. If you don’t care, we don’t care. If you don’t want to learn, we don’t want to teach. What happens here is your responsibility.” Everyone was present and raptly attentive. I had no idea if I’d done the right thing.

We went on with the session’s exercises. The tension eased as the afternoon progressed, and some excellent posters were produced.

I took the opportunity of talking privately with Guure, then Waare [the two most outstanding participants] about continuing their education. Guure would like to study ag economics and Waare, audiovisual education. I explained that G and I had been asked to suggest two participants for further training in the States, and that we would recommend each of them. I said it might not help, not to expect too much, asked them not to talk to others about it, and they understood.

At the end of the day, [participant] Abdirisak brought the following letter:

Dear Teachers,

We know that you have crossed over seas and continents just to give us an aid; we know that we are the people who need your help; we are the people whose service is extension; we are the people who should exploit the time as well as you.

Any way it is due to our foolishness to waste any time at all, but we expect and request you to be patient to our mistakes as much as you can and we will try our best to do better ever since now. We are indeed sorry to make you annoyed.

Your students

So it was OK to get mad — OK in the sense of not doing irreparable harm. There’s something to be said for righteous anger, I suppose, but I still wish It hadn’t happened and feel some depression. I don’t like myself when I’m angry.

* * *

Forty years later, as I was preparing this blog post, I conferred with Waare — then-President (Governor) of HirShebelle State of Somalia — about his views of that incident. Here’s his response (edited for space):

I remember… our awkward attempts…to understand each other and bond (us, young impatient bucks, full of energy and arrogance, rebelling against this young foreign woman)….I remember one particularly rowdy session. …We used to take a few hours of siësta, and we would linger in sleep or in the showers. And in that particular afternoon, not only were we late, for some reason we wouldn’t listen.

But that incident made you in our eyes. You showed us that you wouldn’t be pushed around. We were embarrassed and a little bit afraid (after all, we were paid civil servants!)…We had to come together and make things right! We sent Hawa as our emissary. Because we were shown the fools that we were. Righteous Anger is good and works. Even with a little drama!

* * *

I still have the participants’ letter, the paper yellowed and fragile, the words a reminder of how young high school graduates and a thirty-something woman can meet across the divide of culture, age and experience, both finding maturity through tribulation.

* * *

March 13

G took the first session on “Methods: Giving a Talk.” I felt he broke a lot of nonformal ed principles (e.g., asking for contributions but not writing all of them down, not involving the group, not following the lesson plan, answering his own questions, etc.), but the participants rated his lecture highly. Perhaps that’s what counts in the end. He’s going to introduce report forms and talk about them next week, a topic suggested by Joe and with whom G has coordinated. I’ll try to find some other things also. The participants want to hear from him. The trick is to find subject matter and methodology that’ll work.

I took the second half of the morning, responding to participants’ expressed need to talk about the problems of living in a village. Most grew up in urban areas and are apprehensive about village-living. (One solution, as in China, is to train ext. agents from villages, but that’s not the case here.) They had a good list of problems and possible solutions, although some of the latter concern me. One group came up with a lot of “the govt. ought to’s” (e.g., give us Vespas, radios, houses, etc.) With a $3,000,000 food shortage here, that’s not only unrealistic; it’s selfish. Another concern — some participants feel they can have a girlfriend in the village, altho I suspect, and other participants confirm, that would jeopardize their standing in a conservative Muslim society.

Feel in need of a change of pace and place. Can’t go on the field trip Saturday, because G already made a strong plea for it. We can’t both go, because we’re taking participants’ places. Asked [Bonka official] Yusuf whether anyone was going anywhere, and he said he’d take me tomorrow to his village to meet his mother. Very touched.

March 14

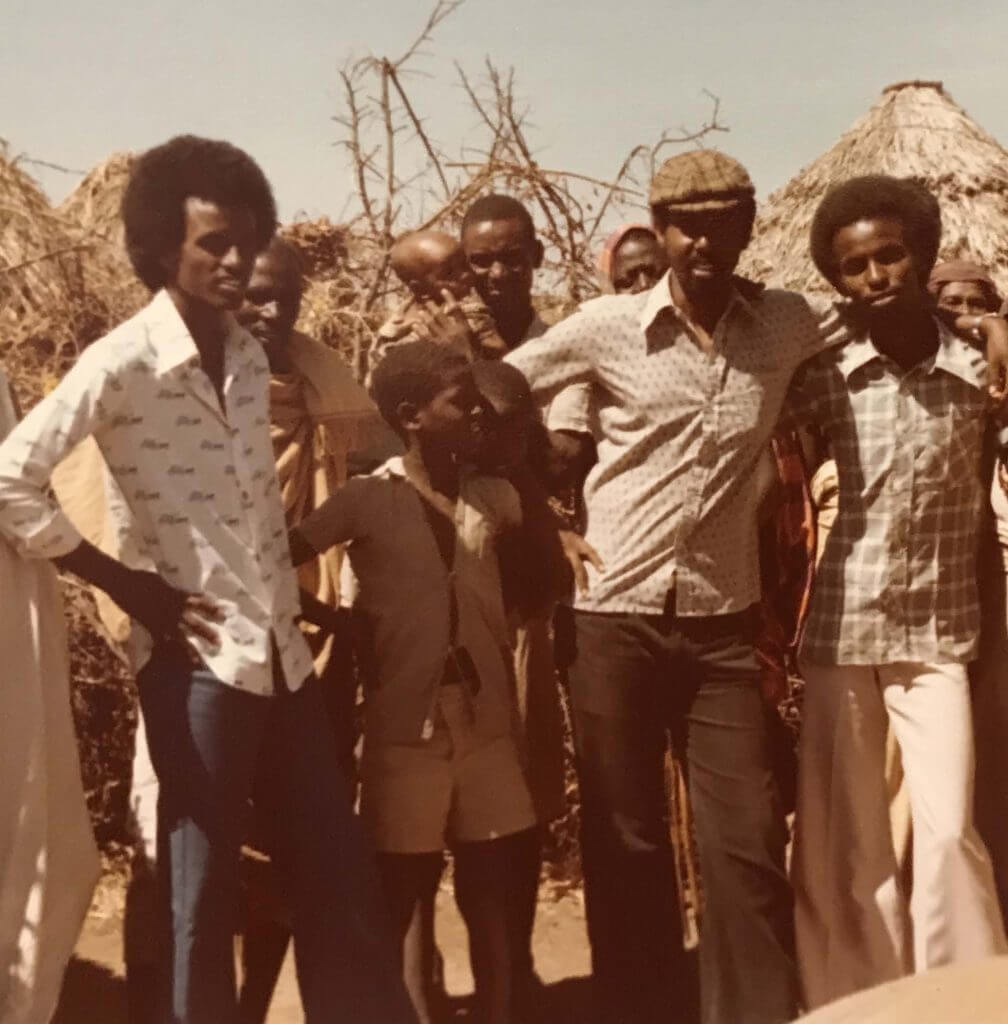

Up early and to Yusuf’s village, Berdale, by Land Rover, about an hour from Baidoa: hundreds of camels, all of us ankle-deep in dried dung, a distinctive but not unpleasant smell, men drawing water in leather buckets from a 15-meter-deep well, everyone staring at me and gathering around.

They ask if I’m Yusuf’s sister and why my skin is so light. I have on a hat, but my hair, clasped behind, hangs down. They find its color and texture amazing. They don’t know countries and haven’t a clue where I’m from. One man asks if I came to get a husband, and when I say I already have a husband and hold up my left hand with its gold band, he repeats the gesture and everyone breaks into animated talk.

I ask if I can buy camel bells, and everyone wants to know why — “You have no camels.” “I’ll buy some camels and take them to America.” They accept that as reasonable, two bells are brought, and I bargain for them. The man asks Shs. 80 [$1.00 = 6 Shillings.] (Later I learn the crowd said, “Ask 100!”) I counter with Shs. 60. Much discussion among the Somalis, then he agrees.

I ask if I can buy camel bells, and everyone wants to know why — “You have no camels.” “I’ll buy some camels and take them to America.” They accept that as reasonable, two bells are brought, and I bargain for them. The man asks Shs. 80 [$1.00 = 6 Shillings.] (Later I learn the crowd said, “Ask 100!”) I counter with Shs. 60. Much discussion among the Somalis, then he agrees.

Next, we visit Yusuf’s mother, who welcomes us into her traditional house furnished with low stools, grass-mat-covered beds and a chest from which she pulls an old carved milk jug for a baby and gives it to me. I’m just undone and searching through my purse, find a half-used bar of Jean Nate´ soap which I offer her to the delight of everyone in the house. She has 14 children and several grandchildren, looking much younger than I’d expected. Her first husband died, and she remarried. Must be a helluva woman.

* * *

I have a thing about camels. I’m not sure why. Being with them seems like something central to me. For me, it’s a feeling. For Somalis, the camel is crucial to life and culture. As is poetry. The Somalis have a long tradition of poetry, often lengthy epics recited from memory by bards as the ancient Greeks did. Here’re two excerpts from a poem by Raage Ugaas (d. 1880s), considered by many Somalis their greatest poet:

The milch-camel

Morning has come, and she stirs and bustles.

She feeds her calf and then for a while

The flow of her milk is checked.

O you who make such a sound of beauty with your bellow

O you who so blithely give voice to your bubbling growl

It is you I call!

…………………..

When the sky is shorn of clouds

And the moon has doffed her halo,

Then parching heat dries up the land.

Many trees have lost their leafy shade

And even the garas leaves are green no longer.

The supply of milk grows scanty –

But on her one can still depend

For she will never fail her master.

It is you I call –

You who stretch your neck to find the leaves

That sprout on branches high above the ground,

When elsewhere there is nothing to be found –

See! The round bowl is full of frothy milk!

(Translation by B.W. Andrzejewski and Sheila Andrzjewski)

* * *

March 16

March 16

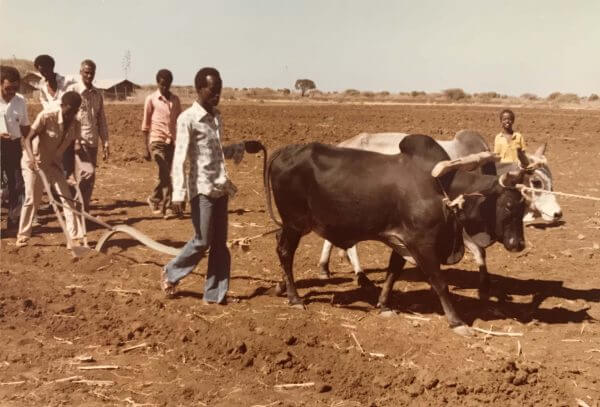

Joe arranged an oxen-plowing demonstration, and we all went to the fields to observe. [Most Somali soils are too thin for mechanized methods, so one focus of the USAID/USDA project was aimed at helping farmers be more effective with traditional plows.] Back in the classroom, Joe gave a talk on what makes a seeing-is-believing demo successful.

G told me he’s missing Shs.2400 ($400)of the money Dugseyeh gave us to buy course materials. G doesn’t know where it is and is reticent to talk about whether or not it might be at the house. My fear: whoever has been pinching beer and soda there has pinched the money too.

March 17

The day started with Ethiopian MIGs and anti-aircraft fire over Baidoa. It’s not clear what the planes were doing, but a nearby village was bombed yesterday, and there are rumors of poison gas and napalm being used on villages and refugee camps to the north. The plan of the Ethiopians seems to be to do as much damage as possible before the Americans establish bases, arm and train the Somalis. The security briefing for Americans last week indicated that this sort of thing would continue, probably reaching as far as Mogadishu. I’m not worried, only angry. It’s easy to bomb villages. I hope we can finish the course in peace.

Joe lectured on the role of the agronomist in extension work, followed by G’s workshop on reports. Joe volunteered that G blew it — wrong information written on the forms, talking about how farm safety reports result in improved tractors in his state, not introducing the concept and relating it to the Somali situation, etc. I wish it could be better. Joe and I put a lot of effort into developing simple forms that could make a difference here.

During the morning, many truckloads of soldiers and artillery were moving toward the border. As we left Bonka at 7 pm, we found that soldiers had cordoned off the road beyond the training center. They stopped our Land Rover for a short inspection before we continued to Baidoa, giving a lift to one soldier. At the usual checkpoint outside town, the soldiers required a more careful ID than usual. In spite of the clear and present danger, the soldiers are so helpful and unthreatening that I can’t help but favorably compare our experiences here with roadblocks in Kenya and Tanzania where the soldiers really took advantage. As we were driving between Bonka and Baidoa, I realized that regardless of what has happened or will happen, a part of me will be sorry to leave.

March 18

Discovered that half the class is sick with malaria and/or dysentery. The conditions and practices in the Bonka kitchen are appalling. I’ve called this to the AID officer’s attention and this afternoon repeated to some of the powers-that-be that Bonka can’t be a full-time training center with the kitchen getting participants sick on a regular basis.

Excused and doctored the sick, helped remainder work on individual projects, learned two words of address for respected older man, “adeer” (“uncle” in Somali, pronounced “ah-dair”) and “au” (“father” in the local dialect). [We had two older male participants, and I began calling the eldest “au” and the younger “adeer.”]

March 21

Washed clothes, self and hair. Ag engineer G.O. came by to take me to his house where I was to share the cooking for the Americans’ weekly Friday get-together.

When we got out of the car, G.O. grabbed my arm and slung me to the ground, shouting, “Baby sister, get down in this ditch!” Then he jumped on top of me. Oh great, I thought, I’m about to be raped by a septuagenarian ag engineer.

But G.O. had been in Vietnam and recognized the sound of a jet flying in low before I did. We heard something popping, and G.O. said it was either gas or pathogen canisters. We lay there until all was quiet. Then I went inside and cooked dinner while G.O. went off to get the Lopezes and G. As we were sitting down to eat, Abdulkadir came by with the news that the army base at Wanlaweyn was seriously bombed this morning.

March 22

G gave a morning lecture on ag journalism while Joe and I went into Baidoa to pick up course supplies. When we returned, I caught sight of a blackboard with details about a Celtics-Royals game and had my worst fears confirmed when participants said a Celtics film was part of the morning’s lesson. What in hell do the Boston Celtics have to do with Somalis learning about ag journalism? I’m really disappointed and angry. Luckily, G had already gone home. With four course-days left, all of them devoted to participants’ presentations, it’s pointless to take this up with him.

March 23

Participants’ final presentations started today. Having them speak Somali with a commentary by a peer in English is working well. Participants who seemed withdrawn are really able to shine, reinforcing our impression that they learned something useful.

Home to discover a big cache of mail from all the folks I love. Read each one twice and wrote one response. Will write rest tomorrow.

As I settled down on the couch for my nightly sleep, Sandra and Joe found a rat in [son] Fred’s bedroom, shut the door so it couldn’t escape and chased it with sticks until they cornered and killed it. No traps in Baidoa, so their rat-battle not unusual.

March 24

G now feels he’s been robbed. In addition to missing sodas and beers, he’s now missing Italian lira, and his travellers checks were messed up. He now believes the Shs. 2400 were stolen. I suggested he talk with Abdulkadir while I oversaw the participants’ presentations.

When the session was almost over, Abdulkadir and G.O. came in and signed that they wanted to talk with me. I passed a note asking of it could wait ’til the current presentation was over. No. Just then, the participant finished, so I gave everyone a ten-minute break and went off to the hen-house (honest) with G.O. and A.

They wanted to talk about G. Abdulkadir said, “I don’t know what I can do — he didn’t lock his door, and we didn’t hire that maid, so it’s not our fault.” Turns out G’s predecessor at the guesthouse fired the maid employed by Project Manager Abdulkadir and hired this woman whom he met in the market. G then kept her on.

They asked me to relate what I knew, so I did: Before we arrived, I’d talked with G about what I understand to be the Muslim view of property — it’s up to the owner to protect it. I’d mentioned the sin of temptation — it’s as wrong to tempt others as it is to steal. I’d cautioned him about not projecting his morality on others in their own country. When the sodas and beers went missing, I’d recommended that G lock the remainder up, which he didn’t do until I made a strong issue of it. When I’d found out he was leaving his key with the guards and not locking his house, I’d counseled him that it was unwise. When the Shs. 2400 had gone missing, I’d suggested it might have been stolen. Throughout all this, G had refused to talk about the basic issue, refused advice and let me know that it was his business. I summed up by saying he’s been both foolish and stubborn. Abdulkadir said he doubts if there’s anything he can do, but he’ll at least talk with the maid. G.O. said, “Old G will have to chalk this one up to experience,” and the meeting broke up.

March 26

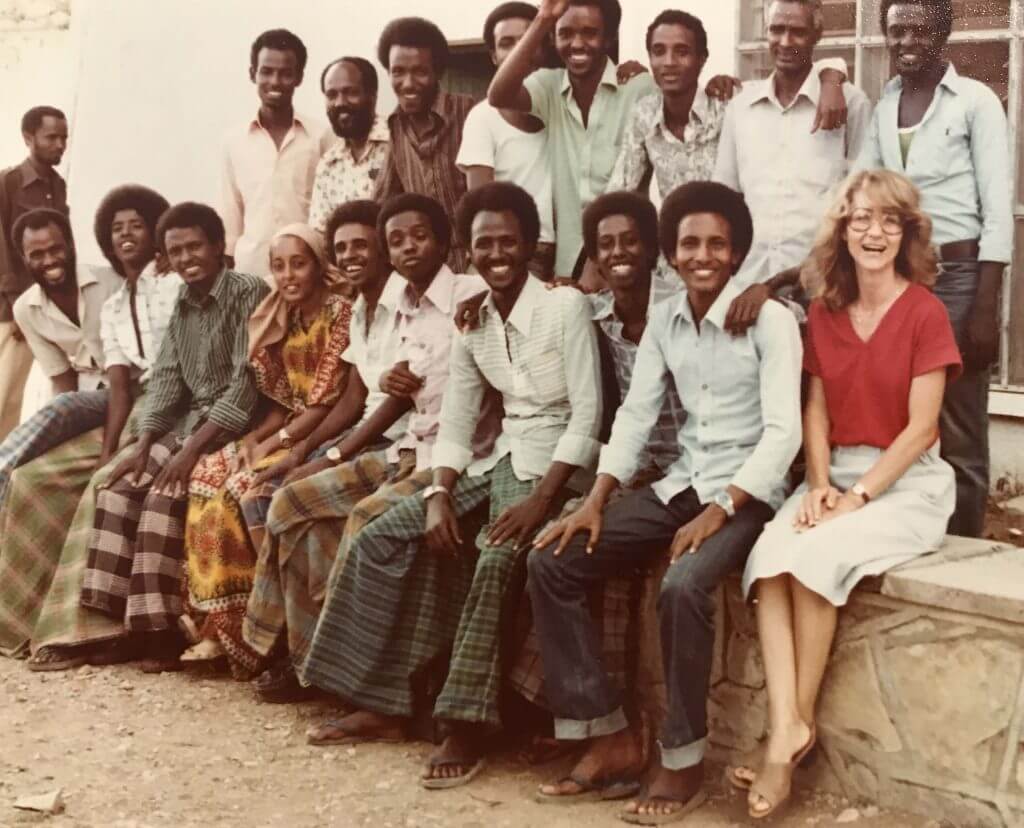

End-of-course party, planned by the participants. A skit with Abdirisak trying to persuade three wayward farmers — Mustafa, Ahmed and Waare — to plant in rows instead of casting the seed broadly: “My wife won’t let me…” Traditional northern dancing, Somali love songs by Waare and Awale, some very subdued Western dancing (“Freak out!”, shuffle, shuffle) and an abundance of Cokes, samosas and biscuits [i.e. cookies].

Baidoa – Mogadishu

March 27

Graduation day. I put on my blue dress because on the first day of class, the participants said blue was the best color because it’s the color of Somalia’s flag and the sky.

We started with the participants looking at what they’d written as their expectations on the first day and discussed in small groups whether or not their expectations had been met. After every group had reported, we talked about why some of these expectations might not have been met and what we could do about it — other courses, enhanced communication resources, etc.

Took forever to get the graduation ceremony started because of logistical and high-ranking personnel problems, but once it got going, it went well. Guure was M.C. Waare made a very nice speech about the course. G made a nice speech about the course and his home state. I talked about the journey we’d begun together but must finish alone. The high-ranking men spoke in Somali. The participants gave us traditional red sandals. I was very touched at their thoughtfulness — and mine are the right size! We gave out the Certificates of Achievement which I’d been lettering for days.

Then a series of SNAFUs as we tried to get out of town and back to Mogadishu — celebratory lunch delayed for 45 min., transport problems, rain turning road to sea of treacherous black-cotton soil. We finally left Baidoa at 4:30, three hours late, carrying participants Hawa, Hirabe, Suleiman and AbdiSaid. A beautiful trip through setting sun, rain showers and finally darkness.

Arrived at hotel at 8:30 — no rooms, despite previously reserving them. Talked desk clerk into giving G a suite and me one with sewage-soaked rug and no key — all that was left. G obstreperous throughout and not cooperating, taking every move, even those aimed at putting pressure on the desk clerk, personally.

Mogadishu

March 28

Got moved into dry-carpeted room with key (plus working air conditioner and stopped-up toilet). Various de-briefing meetings, including one with AID Mission Chief, who began by addressing his remarks to G, only talking to me also after I’d made some professional comments.

March 29

Hawa surprised me with a true embarrassment of gifts: a mahawis for Russell [the traditional wrap worn by men as their lower garment], sandals and a small bag for me. I was overwhelmed and asked what I could send her from the States. Her unhesitating reply: a long blue jean skirt and a blue jean handbag. So it shall be.

March 30

G met with the ranking AID project officer about his $400 theft. I gathered that he gave G no satisfaction. Yesterday, Dugseyeh had indicated that he felt the loss was due in part to G’s carelessness and that he would abide by the AID officer’s decision. G is going to reimburse the Ministry out of his own pocket. A sad ending to a sad song.

April 3

Checked through Security at the airport, then held literally standing on the tarmac in the sun for an hour. After we boarded the plane, we sat sweltering for another 30 minutes. Then we were finally up and away — away from Mogadishu, away from Somalia, going home. But with the hope I’ll return.

* * *

Now, forty years later, I look back and see what I failed to realize at the time:

- Even in Rome, G was exhibiting culture shock as he persisted in telling a restauranteur how they made spaghetti where he came from. As you might imagine, the Italian was tight-lipped. Somalia must have been an exponential shock, and G’s response was to persist in behaviors that had worked for him back home.

- He was a significantly more traditional male than I was used to. My father was “liberated” long before anyone knew what that term meant, and Russell never treated me as anything other than a true partner in all our endeavors. Near the end of the course, G told me that his deceased wife used to take care of him in all things; now that she’d passed, he ate cold cereal and milk for breakfast and lunch, while his “girlfriend” brought dinner every night.

- G was used to lecturing, not interactive training. Besides, he had a hearing disability and had trouble understanding Somali English. No wonder he retreated into what he knew and showed basketball movies when he couldn’t do what he was comfortable with.

I observed all that but didn’t connect the dots. With a little more experience, I might have nurtured a better interaction for everyone. Better for G, better for the participants, better for all of us.

A final coda: Once home, I went to see our family doctor because my ankle had been hurting throughout the whole time away. He was kind of a crusty old guy, and after looking at the x-ray, he said, “You a ballerina?”

“Nope.”

“Olympic skier?”

“Nope.”

“Champion figure-skater?”

“Nope.”

“Well if you were, we might fix it. Broke and healed on its own. Not worth re-breaking and setting. You can live with it.”

And I did.

COMING IN MARCH: More from the 1980s –Turtles, horses and motorbike molesters

* * *

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU: nancy@nancyswing.com

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.