#53: Italy and Beyond, July – December 2003

Travels and Travails

The last six months of 2003 were filled with trips (Budapest, Venice and Sri Lanka), plus back-home challenges with hunters and a landslide almost hitting our propane tank. Here are edited excerpts from letters home to family and friends. (As always, you can click on photos to enlarge them.)

July

Stepsister Mary Anne brought all the girls in her family to visit, and I did my best to show them a good time, visiting Porto Ercole on the West coast, ceramic center Deruta north of here, Assisi further north and east, then putting them on the train to Florence.

I must say they were all good sports, not the least because they arrived in the midst of our third heat wave this year. It’s been a tough summer, starting in May with record high temperatures. The River Po is down to its lowest level since they started measuring it in the 1860s, and forest fires are breaking out all over the peninsula. We’ve had day after day of temps in the high nineties with high humidity. Normally, we’d be in the eighties, with low humidity. I’m struggling just to keep things alive in the garden.

Poor Russell arrived home in the middle of this heat — higher than in Colombo! — at 10 p.m. the night after Mary Anne et al. left for Florence. I can’t tell you how pleased everyone in Amelia was to see him. The owner of the local bar insisted on treating us to coffee and pastry, and everyone was coming up for hugs and kisses.

We leave tomorrow (the 30th) for an overnight in Rome before catching a 6:55 a.m. train to Vienna. We’ll take a hydrofoil down the Danube to Budapest, staying five nights, returning to Vienna by afternoon train, then a night train down to Rome. We love trains and boats, and we love the act of traveling itself — the point being not just to get there, but to enjoy the trip — so we’re very much looking forward to the next eight days.

August

Some months after the 1956 Hungarian uprising, a refugee family came to my parents’ door selling eggs. They’d managed to escape and make their way to West Virginia, where they somehow had the resources to raise chickens. For years, my mother bought her weekly supply from a rosy-cheeked lady with upturned nose and kerchiefed head.

My thoughts kept returning to that family as Russell and I visited Budapest, traveling from Vienna by hydrofoil. We’d been warned that the Danube was low, but I’d expected it to be wide. At least in that section, the river is narrower than the Ohio I grew up with. We passed through two locks, one of which was exceptionally deep. By the time we’d reached the bottom level, we had to crane our necks way back to see the sky.

Arriving by river must be the best way to meet Budapest. Our first sight was of the Varhegy, or Castle Hill, a long, fortified plateau crowned by a huge palace, fanciful bastions and church spires. Then we passed the neo-Gothic Parliament, decelerated under the Chain Bridge and arrived at the International Dock, where we went through Customs without incident. (I was told it used to be An Ordeal.)

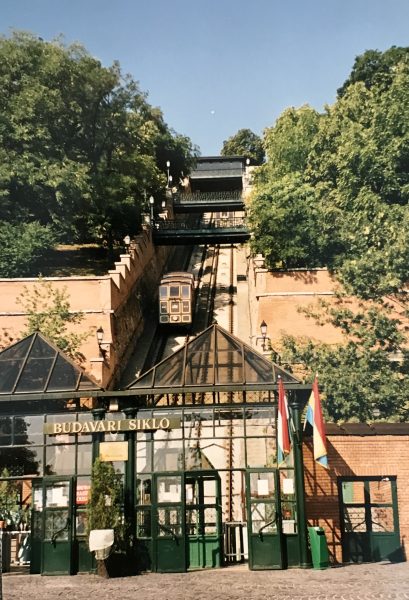

Our hotel was just below the fortress, housed in a 300 year-old mansion with a flowered courtyard. Overlooking this was our suite — a small sitting room, huge bedroom, good-sized bathroom, all decorated in reproduction Art Nouveau. Very inexpensive by western European standards, with a nice breakfast buffet included. Only a short walk away was the funicular constructed in the 19th century to ease the long trip up to the Varhegy.

We took that funicular almost every day. The palace now houses four museums, but we enjoyed walking in the old residential district as much as anything. Winding streets lead past the neo-gothic Matyas Church, a medieval Jewish prayer house and fascinating mansions with steeply sloping roofs and lovely gardens glimpsed through archways. All around were marvelous views from the fortified walls of the two cities now joined as one, Buda and Pest.

We took that funicular almost every day. The palace now houses four museums, but we enjoyed walking in the old residential district as much as anything. Winding streets lead past the neo-gothic Matyas Church, a medieval Jewish prayer house and fascinating mansions with steeply sloping roofs and lovely gardens glimpsed through archways. All around were marvelous views from the fortified walls of the two cities now joined as one, Buda and Pest.

I’d been told that Budapest was full of temptation in the form of coffee houses famous for their pastries. We gave into temptation daily, feeling we had an obligation to try each cafe in order to make a fair judgement about who had the best strudel.

Budapest is an extremely cultured city. Every evening, we attended a performance. An open-air concert of arias by Hungary’s foremost opera stars and the national symphony orchestra was hosted in the plaza before St. Stephen’s Basilica, a magical setting under the stars. Another evening, we were entertained by folk dances from this exceptionallly multicultural society.

We also went to the movies — in English! — traveling by excellent metro to a multi-storied, ultra-modern shopping mall with a Cineplex. Now that communism has fallen, the Hungarians seem to have taken whole-heartedly to commerce. The old market has been refurbished and entices visitor and resident alike with stalls of breads, sausages, cheeses, fruits and flowers. In downtown Pest, a whole commercial street has been turned into a blocks-long pedestrian mall with shops selling everything from pricey European cosmetics to designer clothes.

We also went to the movies — in English! — traveling by excellent metro to a multi-storied, ultra-modern shopping mall with a Cineplex. Now that communism has fallen, the Hungarians seem to have taken whole-heartedly to commerce. The old market has been refurbished and entices visitor and resident alike with stalls of breads, sausages, cheeses, fruits and flowers. In downtown Pest, a whole commercial street has been turned into a blocks-long pedestrian mall with shops selling everything from pricey European cosmetics to designer clothes.

My favorite shopping was at the national handicraft outlet, where I kept eying a black wool coat embroidered in red with traditional motifs. I managed to convince myself that I didn’t really need it and instead bought the typical painted eggs of Hungary for friends back in Amelia. As I gazed at the intricate designs, my thoughts went back to that refugee woman who came to our door almost fifty years ago.

Once we got home, we had only a day to get Russell ready to return to Colombo, but somehow we managed to send him off. With Russell gone, it was time to bear down again on the book, having taken a hiatus during the busy summer. I’ve spent the last three weeks re-reading my previous edit, polishing words and phrases here and there. I think it’s almost ready to send out to interested agents again, but I want to let it sit for a week while I contemplate totally rewriting the two chapters narrating my most troublesome scene.

All of Europe has continued to swelter with record temperatures. Many of Budapest’s trees had turned brown and were dropping leaves. Thousands of senior citizens have died in France. Forest fires have raged from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. Here, we’ve actually had higher temps for longer than most countries on the far side of the Alps, but we seem to have suffered fewer casualties of all types. Although not many houses are air-conditioned, they’re built of thick-walled masonry with high ceilings and shutters that help control the temperature. Because our climate is relatively dry, it cools down in the evening, so we’ve all been able to sleep most nights. The strength of the extended Italian family means that old folks are not institutionalized or alone in apartments, but being cared for by loved ones.

Graziano and I have been cleaning up the old, round cistern, engulfed in what local folk call “the Russian vine” (as opposed to “the American vine,” Virginia Creeper). Not sure what the Russian vine is, but it’s really tenacious and not at all attractive. Last spring, one of my English-lady friends gave me some cuttings of rosea banksia, a wonderful vining rose that does well in this climate. Graziano has chopped down the Russian vine, and we’ll slice back the roots and apply kerosene to the raw cuts in hopes of killing it off. I’ve started chipping away the stucco that remains on the outside, getting down to the old salmony brick. If all goes well, we’ll finish everything in time for the rainy season to give banksia a kick-start. Over the past seven years, we’ve been filing up the eight feet of cistern that’s below ground with rubble from our various projects. Another year of this, and we should be ready to lay pavement over the rubble, order a new metal door and turn this old, no-longer-useful eyesore into a rose-covered, round storeroom for mowers, etc.

Graziano and I have been cleaning up the old, round cistern, engulfed in what local folk call “the Russian vine” (as opposed to “the American vine,” Virginia Creeper). Not sure what the Russian vine is, but it’s really tenacious and not at all attractive. Last spring, one of my English-lady friends gave me some cuttings of rosea banksia, a wonderful vining rose that does well in this climate. Graziano has chopped down the Russian vine, and we’ll slice back the roots and apply kerosene to the raw cuts in hopes of killing it off. I’ve started chipping away the stucco that remains on the outside, getting down to the old salmony brick. If all goes well, we’ll finish everything in time for the rainy season to give banksia a kick-start. Over the past seven years, we’ve been filing up the eight feet of cistern that’s below ground with rubble from our various projects. Another year of this, and we should be ready to lay pavement over the rubble, order a new metal door and turn this old, no-longer-useful eyesore into a rose-covered, round storeroom for mowers, etc.

September

With the turning of the calendar came the turning of the seasons. Even though it was lots cooler, the rains still didn’t come, and the olive harvest was in jeopardy — a nuisance for me, but a disaster for my neighbors, who need the income. Thankfully, September is ending with several days of dispersed and rather gentle rain. Too soon to tell, but the olives might be saved.

The onerous task of reviewing and polishing the book complete, I decided I needed a break to get a little psychological distance before starting the next phase. So off I went to Venice on the train, visiting parts of the city that had always intrigued me, but where I’d never been.

I took the vaporetto over to the cemetery island one day and paid homage at the graves of famous artists buried there. I was most moved by Diaghilev’s and Brodsky’s. Both are off to the side, in separate, ill-kempt sections termed “Greco” (i.e., Orthodox) and “Protestante” (the catchall phrase for everyone else who’s not Catholic, including the Jewish Brodsky). Resting atop the gravestone of the Ballet Russe impresario were the usual flowers and candles, but also several toe-slippers, one of which was quite new. Poet Brodsky’s grave was graced with scores of pencils and pens. On all the Russian graves were cairns of small stones signifying pilgrimages, such as we had seen when we lived in the former Soviet Union. Poor Ezra Pound had nothing — no flowers, no candles, no pens, no stones, just a nearly overgrown but elaborate plot. I left my own token on each grave, a red rose bud.

Another day, I went to Giudecca (jew-day-kah), an island visible from the edge of Piazza San Marco, but tourists rarely visit. I walked all over and found it absolutely enchanting — lots of gardens (rare in Venice), old workmen’s houses, narrow streets ending in small squares, canals winding here and there. If I were to live in Venice, this is where I would be.

September ended with a country-wide blackout. The power was out when I first got up, but I thought it would return in 15-30 minutes, as usual after rain in the night. No power by 10 a.m., so I checked our circuit-breaker (not the problem), then called neighbors Ornella and Paolo, learning the electricity had been out since 3 a.m. Around 1:00, still with no power, I called friends Elisabetta and Umbro in town, discovering they didn’t know any more than I did, although everyone was wondering about earthquake or terrorism. At around 2:30, just as I was beginning to consider how to get water out of the large tank in the outbuilding to flush the toilets (no electricity = no pump = no water = no toilet tanks refilled), I heard the hum of electricity returning to the fridge. Now I’m thinking about disaster-preparedness, including tinned food (rarely eaten here), a 2-meter hose so I can siphon the water tank, something like a Coleman lantern, etc.

Closing with a piece I wrote marking the change of seasons (apologies for the inability to type all the Italian diacritical marks with an English-language program).

—————————–

WEEKEND WARRIORS

BANG! BANG! It’s midnight, and someone is shooting guns very near the house. BANG! Why are they shooting? Are they shooting each other?

I get up and look out the West windows. There, in the field that surrounds us, is a vehicle with lots of lights tearing toward our olive grove. BANG! Zack is at the top of the stairs, whining and hitting the door. BANG! Are the carabinieri chasing someone? But it’s a very loud motor, more a tractor or four-wheel drive, not a cop car. BANG!

I’m not sure what to do. Then I think I’d better crouch down in case there’s a stray bullet. BANG! BANG! Call Ornella and Paolo? How do you say “shoot” and “gun” in Italian? I grope for the dictionary in the dark. BANG! BANG!

Then I think of phoning English-speaking Umbro. His family has just come in from dinner out, so I don’t wake them. He says it’s probably men out hunting wild boar, or maybe hares. It’s illegal, but they do it. BANG! He asks several times if I want him to call the carabinieri, but I say no, even though I’m feeling uneasy. By the time they got here on our unpaved roads, the four-wheel drive would be long gone across the fields.

We hang up, and I go back to the window, but all is dark and quiet now. I return to bed, still feeling uneasy, thinking how flimsily the field gates are closed, recalling the downstairs is shuttered and Zack’s in the foyer. Finally, I go to sleep.

The next morning, as Zack and I set out for his walk, I see a group of hunters in the next field with their dogs. They see me, too, so I change direction and head Zack across the middle of our olive grove to keep him as far from the hunting dogs as possible. He’s really agitated, running back and forth on the long leash, smelling here and there.

As we near the southern edge of our olive grove and start across our open field toward the gate of the fence around the house, he becomes more agitated and keeps looking back. When we get to the bamboo below the gate, several hunting dogs come running out of our olive grove toward us.

I scream again and again to scare them off. I can just barely keep Zack under control with the leash shortened as far as it will go. I shout, “Aiuto!” (Help!)

The hunters come into view, and I’m absolutely furious. “Nessuna caccia qui! C’e un cartello! E la mia terra! La legge e a 500 metri dalla casa! Nessuna caccia qui!” (No hunting here! There’s a sign! It’s my land! The law is 500 meters from the house! No hunting here!)

“O, signora,” comes the disdainful reply, “non si preoccupi” (Oh, lady, don’t worry yourself.) And off they go down into the next field.

I hate hunting season.

—————————–

October/November

Writing this from Sri Lanka, where I’m spending time with Russell until mid-November. Let me back up to October and bring you up to date.

Before departing, I completed the “final” revision of the book and sent it off to the agents who’d expressed interest last spring and made some suggestions after reading the first 50 pp.

Graziano’s constructing a stone barrier along the foot of the fence because of another hunting incident. In mid-October, 4-5 rabbit hunters and their pack repeatedly came right up to the fence which is only a few yards from the house. A distance this short is totally illegal. Zack finally had enough of this torment, dug a hole under the fence and took off to teach the dogs a lesson.

I was on the other side of the house, but luckily, Graziano saw Zack running through the olive grove and started after him. I heard G shouting at Zack, ran around the house, saw Zack wrecking havoc among the pack, grabbed his leash and started running down the neighbor’s newly plowed field to the fray. One of the hunters had his rifle trained on Zack and was threatening to shoot him, but Graziano told him to wait for the signora to arrive. When I did, the hunters called their pack off Zack, and he responded to my command.

I got him on the leash and walked him back to the corner of our property, one hunter shouting, “Next time, we’ll shoot!” G came up the hill, and we led Zack to the house, chained him to his lead and doctored his nose where the pack had done superficial damage. We then went back down the hill to help one of the hunters find his dog, which had run off to hide.

Hunter, Graziano and I kept traipsing through a field of feed corn, but we didn’t find the dog. G told the hunter the signora was sorry, and the hunter replied that everyone was sorry. Both G&I expected the man to show up with a bill, either for the dog or for veterinary services, but he never did. Perhaps this was an acknowledgment that hunters and dogs were also at fault.

Now that I’m in Colombo, Russell has to work for much of the time, but we set aside a long weekend to visit “the Cultural Triangle” to the north.

R’s driver, Kumar, drove us northeast from Colombo to the Kandalama Hotel outside Dambula. Designed by Sri Lanka’s most prominent architect, Geoffrey Bawa, the hotel sits, huddled against a giant rock, above a “tank” (one of the myriad ancient reservoirs created by Sri Lankan kings as part of a sophisticated irrigation system all over that part of the island). That afternoon, we visited the nearby Dambula cave temples, where Buddhist statues and frescoes have fascinated visitors for centuries.

We drove the next day to Polonnaruwa, the capital of Sri Lanka during the 10th and 11th centuries. City ruins stretch for five miles along one side of a 6000-acre tank and include palaces, temples, Buddha statues, baths and various other structures. A UNESCO World Heritage site, Polonnaruwa has a first-class museum featuring the city’s history and archeological discoveries.

We drove the next day to Polonnaruwa, the capital of Sri Lanka during the 10th and 11th centuries. City ruins stretch for five miles along one side of a 6000-acre tank and include palaces, temples, Buddha statues, baths and various other structures. A UNESCO World Heritage site, Polonnaruwa has a first-class museum featuring the city’s history and archeological discoveries.

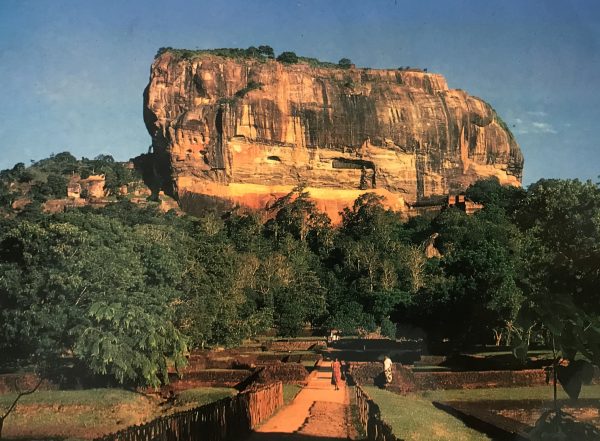

Our third day found us climbing Sigiriya Rock, which rises 600 feet above the surrounding plain. This huge butte was converted into a palace-fortress in the 5th century by a regal parricide, who reigned for 18 years before he cut off his own head (says the myth), rather than be captured. I managed to climb to the plateau halfway to the summit, but Russell went on to the top along a rickety metal staircase rammed into the rock and jutting out into space. The final ascent was not a pleasant experience for those with vertigo, and I had good company down below with others of that persuasion. Meanwhile, R enjoyed touring the ruins above.

Perhaps the two best things about Sigiriya (also a World Heritage Site) are the giant lion paws that remain from a huge statue that guarded the entrance to the final ascent and far below, wonderful water and boulder gardens. The former garden employed hydraulics that would seem quite modern to today’s engineers, and the latter includes giant boulders that create natural arches beneath high shade trees.

Perhaps the two best things about Sigiriya (also a World Heritage Site) are the giant lion paws that remain from a huge statue that guarded the entrance to the final ascent and far below, wonderful water and boulder gardens. The former garden employed hydraulics that would seem quite modern to today’s engineers, and the latter includes giant boulders that create natural arches beneath high shade trees.

Every evening, we ate excellent food on the hotel terrance under the stars, a flute’s gentle notes drifting on the breeze. A pleasure to get a little gussied up and experience the magic. Kandalama is a place we’d gladly return to, just to soothe our senses.

Back home, November ended with a landslide near the house. Four boulders, each over a yard in diameter, came crashing down into the security fence around the propane tank, landing within inches of hitting it.

Graziano, Paolo and I tried to clear some of it, deciding we’d better call the Vigili del Fuoco (firemen) and ask then to come make recommendations about what remained to be done. With three even bigger rocks still up there, we were concerned they might topple too.

Four firemen arrived in a big truck and proceeded with their bureaucratic spiel:

- The tank should never have been located there in the first place; it was a disaster waiting to happen. (It was already there when we bought the house.)

- The tank should have been exchanged for a new one four years ago. Although it belongs to the gas company, it’s my responsibility to make sure that happens (which, of course, I didn’t know).

- They concurred with what G, P & I had already discussed, that the tank should be moved and put underground. It’s my responsibility to call the gas company and get it done ASAP.

- The cliff from which the boulders fell belongs to Sig. D’Annibile, called “il Barone” behind his back because of his demeanor. It’s my responsibility to tell him the cliff must be stabilized ASAP, but the Vigili will back me up.

- Once the tank is underground and I have all the documentation from the gas company, I must take the papers to the head office of the Vigili in Terni (20 miles away) to register the changes.

- On December 7 (which turns out to be a Sunday, as well as the day that will live in infamy, so it’ll have to be the 8th), I must bring all my documents (gas co., Vigili HQ) to the Amelia Vigili office, so they can register them.

I haven’t heard from the agents to whom I sent my manuscript before leaving for Colombo. The Writer’s Guide says it generally takes a couple months for an MS to be read and a response written, so I’m trying to be patient.

On the good news side, Graziano and I spent four days harvesting 810 kg (1782 pounds) of olives, yielding 117 kg (257.4 pounds) of extra-virgin olive oil. Despite the terrible, hot, dry summer, we ended up with an excellent harvest in terms of quantity and quality, thanks to the fall rains.

COMING NEXT MONTH

#54: Italy and More, January – June 2004

A Tale of Two Cisterns plus

Zurich, Dubai, USA and Winchester, UK

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.