#29: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1995 Early Days

Moving is said to be one of the most stressful experiences in life — second only to losing a spouse. People who work in international development may move every two years, across great distances, to wildly different climates. Edited from letters to the family, here’s our story of moving from Honolulu, Hawaii to Almaty, Kazakhstan.

At the time we lived in Kazakhstan, the capital was Almaty (SE corner of country).

In the mid-nineties, Russell served as Field Director of the Central Asian Republics Rule-of-Law Project. Sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by the Washington-based Chemonics consulting firm, this program aimed at strengthening the democratic transition of five newly independent countries emerging from the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Russell’s team of 25 bilingual lawyers, financial advisors and interpreters facilitated training of an independent judiciary, development of grassroots civil-society organizations, citizen access to legal documentation and expert analysis of national constitutions.

Contemplating that move, I wondered if my decades-old experience in another Central Asian country (Afghanistan) would have any relevance to our life in a next-door neighbor.

[Click on photos to enlarge.]February 13

Lots of news from our first four days in Almaty (all-ma-tee’). But let me back up to the prelude, which was a character-builder.

It began with a reversal on our shipment of winter clothes from Fredericksburg, Virginia storage to Almaty. Despite what we’d been promised and just three days before we were due to leave the States, permission to ship by air was denied. [We’d already flown from Honolulu to Washington for meetings prior to continuing on to Kazakhstan.] We sat down with Chemonic’s Project Officer to devise a new plan as follows. I’d exchange our rent-a-car for a van at Dulles Airport, drive to Chemonics to pick up 5 trunks, then drive down to Fredericksburg on the first day. On the second day, I’d go to our storage facility where they were holding our air freight shipment, awaiting instructions. I’d open the shipment, take out what would fit in the trunks, return to storage whatever was left over, drive back to DC and leave 4 trunks with Chemonics for Joseph Luke to bring the following week. He would be flying direct, while we were flying via Rome so Russell could talk with the International Development Law Institute about issues relevant to the project. Our extra stop would have meant that the excess baggage would come under European rules, which have much higher rates than American rules. The fifth trunk would come with us via Rome, half-filled with some of our stuff and half with Chemonics’ stuff (the usual forwarding of mail plus project materials).

I managed to get everything done within the time limits, feeling absolutely elated when I returned to DC. I hauled the trunks up in the elevator and deposited them, as planned, in the Chemonics reception area. Just as I was rushing out the door to move the van before the 3:30 parking limit, the admin. officer for our project arrived and threw a fit because no one had told her about this plan. I sympathized with her distress, but I held firm: it was unreasonable to expect us to go from the tropics to Kazakhstan in midwinter without our warm clothes. She had no power to stop us, so it ended well. But I must say I was also deeply aggrieved to be jumped on for taking the time and trouble to execute the only plan left, when it wasn’t our contractual obligation, but theirs, to get our clothes to Almaty.

Our plane took off from Washington at the end of a big winter storm. The moment we left the ground, we had turbulence for three hours. It was so bad the cabin crew were frequently strapped in, with drink- and meal-service delayed. At one point, they were up serving drinks when the captain’s voice came over the intercom: “Sit down!” No chance to say, “Cabin attendants, please take your seats.” They all jumped into the nearest seats and didn’t have time to buckle up before we hit REALLY bad turbulence. They were buckling while bouncing. Finally, we outflew the storm, and it was smooth from then on into Rome.

Russell’s meetings with IDLI went very well. Meanwhile, I took care of the nitty-gritty of international life — unpacking, getting laundry and dry cleaning done, buying supplies not purchased in DC, repacking, etc.

The last night we were in Rome, R was struck down by severe diarrhea. But he had to get on the plane in a matter of hours, so I dosed him with the prescription which our Hawaiian tropical medicine specialist had given us for just such emergencies. We got him reasonably fit to travel and took off for Frankfort and a connecting flight to Almaty.

When we got to Frankfurt, we learned that our connecting flight was delayed until 8:30 p.m., some 6 hours away. But we kept getting the wrong advice about the correct waiting area. So there we were with Uncle Russ, queasy and weak from his ordeal, schlepping bags and trunk upstairs and down, through tunnels and over walkways, past innumerable security checks (and they’re VERY serious about it in Germany). Finally, we just stopped playing that crazy game, settled down in a couple of recliners in some hallway and waited until it was time to go to our free dinner, compliments of Lufthansa.

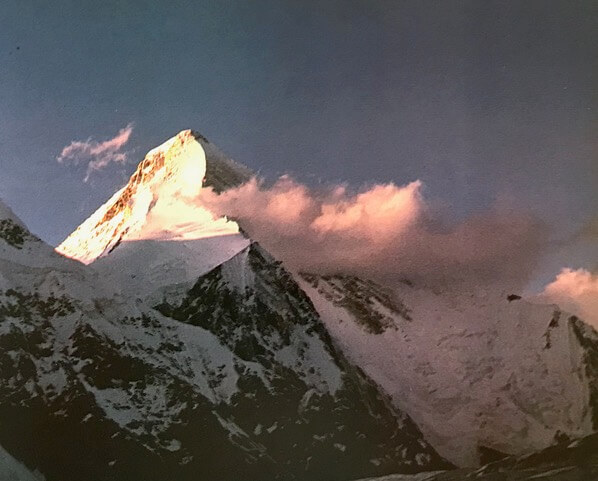

We got on the plane at 9 p.m. and took off with profuse apologies from the carrier — there’d been fog at the Almaty airport, so the round-trip aircraft had been delayed taking off and thus late in arriving at Frankfurt. R slept most of the way, coming alive for food and water. I watched “The River Wild,” read books and magazines, then dozed off somewhere over Asia. When I woke and looked out the window, we were flying by the most incredible sharp-edged, snow-covered mountains gilt by the rising sun. I looked at my watch — only half an hour ’til touchdown!

We got on the plane at 9 p.m. and took off with profuse apologies from the carrier — there’d been fog at the Almaty airport, so the round-trip aircraft had been delayed taking off and thus late in arriving at Frankfurt. R slept most of the way, coming alive for food and water. I watched “The River Wild,” read books and magazines, then dozed off somewhere over Asia. When I woke and looked out the window, we were flying by the most incredible sharp-edged, snow-covered mountains gilt by the rising sun. I looked at my watch — only half an hour ’til touchdown!

Wrong: three-and-a-half hours ’til touchdown. The airport was socked in again. The local officials wanted to divert us to Tashkent, but the pilot was insistent. He had lots of fuel, so he wanted to circle until there was no other choice but to divert. Actually the circling was nice for us, because we had another three hours of sleep. When they eventually said the plane was on final approach, we felt much refreshed.

Getting our baggage and going through Customs was easy, although we had to carry everything ourselves — no porters or baggage carts. We had three suitcases, a trunk and four carry-ons. We dragged the pieces one-by-one across the 20-30 feet from the carousel until all were assembled for a security check. Then we dragged them another 10 feet to Customs, where they didn’t hassle us much, and on another 15 feet to the door and our waiting project driver.

We were met by two Valodyas (the familiar form of “Vladimir”). One was the driver (locally famous as a faith healer), the other the project receptionist, both ethnic Russians. Russell and the two Valodyas took what they could carry, and I stayed behind with what was left. Then Russell remained with the van, while the two Valodyas came back for me, the trunk and my carry-ons.

Looking out the window as we drove through Almaty, I felt delighted to be here. As promised, every street is tree-lined. I saw many old cottages painted in quaint colors, and the public buildings, especially the ones built prior to the Russian Revolution, are quite attractive. Even the Soviet architecture, though heavy and ponderous, is not oppressive. True, the apartment blocks are not pleasing, but the trees soften their drabness.

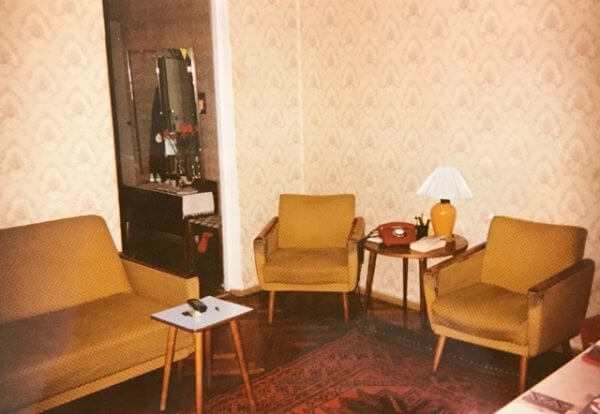

We’re staying temporarily in the project apartment rented for short-term staff. The lift was out-of-order, so we had to carry all that baggage up four flights. The flat itself is spacious, comfortable and well-lit, with a balcony. But it’s also shoddy, with worn, stained upholstery. The building hallways are dirty and ill-lit. Under Communism, there was a system for keeping public areas clean and in working order. With the fall of the Soviet Union, that system has broken down, and there’s not yet a new one to replace it. So far, the toilet-paper holder has fallen out of the wall, and a curtain valance crashed down on my wrist. No bones broken, but it sure didn’t feel good. The project handyman will come fix them.

We’re staying temporarily in the project apartment rented for short-term staff. The lift was out-of-order, so we had to carry all that baggage up four flights. The flat itself is spacious, comfortable and well-lit, with a balcony. But it’s also shoddy, with worn, stained upholstery. The building hallways are dirty and ill-lit. Under Communism, there was a system for keeping public areas clean and in working order. With the fall of the Soviet Union, that system has broken down, and there’s not yet a new one to replace it. So far, the toilet-paper holder has fallen out of the wall, and a curtain valance crashed down on my wrist. No bones broken, but it sure didn’t feel good. The project handyman will come fix them.

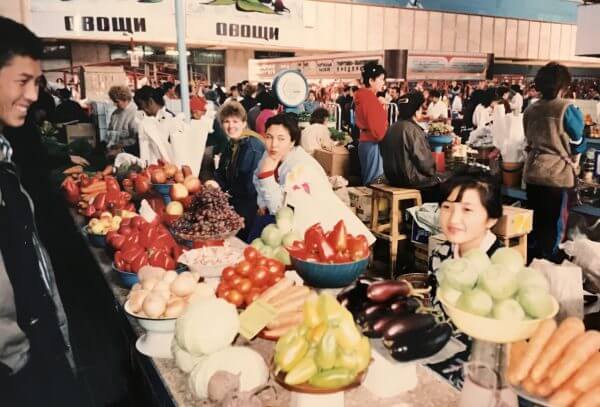

We’ve been to a couple of government stores, the Central Market and a store which only accepted hard currency until recently. Within a few blocks of our apartment, we’ve found shops and kiosks selling juice from Holland (apple, grapefruit, red and white grape, orange, pomegranate), mineral water with and without gas, a variety of breads (both flat and raised), eggs, pasta, rice, cookies, Coke and Pepsi, Danish ham and salami, oranges, apples, and chocolate (one of the seven basic food groups). We also saw street vendors selling long-stemmed roses at $1.50 each, as well as carnations at a lesser price.

It looks like everything you could want is available here. It may be more expensive, but that’s only reasonable, given the length of the supply lines. Something manufactured/canned may not be a name-brand you know (i.e., Turkish toilet paper and Chinese sardines), but it’s likely to be of better quality if imported. It may be of lesser quality if produced in any part of the former Soviet Union. Fruits and vegetables are in abundant supply, even in the dead of winter. Meat looks a bit unappetizing and has to be cooked well-done, but that’s something we’re used to when in the Third World. Fresh fish is an absolute no-no; it won’t kill us to do without it, and it might kill us to do with it, so that’s an easy choice.

Virtually everyone here has a fur hat, and many, many people have fur coats. A teacher makes $30 a month, but fur coats and hats are very cheap by our standards (a rabbit-fur hat costs $6; a fox-fur hat, $55). They’re thought to be a necessity because of the climate. By the way, those teachers get all kinds of perks like subsidized housing, free medical care and a free spa vacation for the whole family, etc. That low salary comes with a lot of extras.

Russell’s project has a housekeeper who comes three times a week to do laundry and clean the apt. The “modern” washing machine is a plastic contraption which fits over the tub, gets filled by hand and holds three undershirts at a time. Everything is rinsed and wrung by hand. Our housekeeper, Alexandra, used to work at a pharmaceutical factory. Now she exists on a minimal pension, so she’s glad of the extra cash, especially now that inflation has pushed the price of goods up. Alexandra’s very pleasant and speaks only Russian. I speak only about three words, but we manage to understand each other. We’ve both got a lot of good will working for us. By the way, the washed clothes are hung in the apt hallway on cords stretched high overhead. Anything that adds moisture to the air is most welcome even if it’s drying laundry.

We’ve started the house-search, meeting with a real estate agent, a totally new profession here. I’m hoping that by this weekend he’ll have something to show us. In the meantime, R’s admin. assistant knows of a house, and we’re going to see it tomorrow. R&I both feel it’ll take a lot of looking before we find something. We’d prefer a quaint, traditional cottage, but then we’d probably have to do some renovating.

After meeting with the agent, I walked up the street in a snow storm to visit the history museum — lots of things that I’d previously only seen in photos — a yurt, the famous double-curved short bow (a technological advantage that helped the Mongols conquer half the known world from horseback), costumes of Central Asian nomads, gorgeous jewelry in silver and gold. The Soviets systematically set out to destroy the cultures of the Central Asian peoples. Now, with the breakup of the Soviet Union, these peoples are trying to regain their heritage. Hopefully, before too many old people die, the younger ones will be able to tap their memories of traditional arts and crafts. A few items from this effort are for sale at the museum — wonderful carvings with fine paint-work, traditional hats of felt and fur, embroidery and rugs.

Last Tuesday, I went shopping with the other “dependent spouse” in the project, a man married to one of the women lawyers. We went to the Central Market, where I stocked up on fruits and vegetables, including two kinds of raisins and dried apricots. Dried fruits are absolutely first-rate here, wonderful flavor. You do have to clean out the stems, wash them thoroughly and then boil before eating, but they’re delicious on hot cereal in the morning.

“Alma Ata,” the Russian version of the Kazakh “Almaty,” means “father of apples,” and scientists think the domestication of the apple may have begun in this part of the world. That’s not hard to believe when you visit the Market. There are many, many varieties, some of which I’ve never seen before, not even in old WV apple orchards. There’s one known as “the American apple,” (our red delicious). They got the original seeds or root stock from the States — how’s that for things going full-circle?

I worked with the U.S. Embassy rep to check our shipment which finally arrived from Hawaii. One box was broken open, probably just from rough handling, not theft. We seem to be missing a box labeled “files,” which was inside that box. Hope it’s not income tax papers. I’d rather have lost dishes or glasses. At least those can be replaced. They’ve put a tracer on the box, but we’re not too sanguine we’ll ever see it.

Joseph Luke arrived this morning after many delays, along with our trunks of winter clothes from VA. I opened them to find everything smelling stale after four years in storage. Some things can be washed, but what do we do about the lack of dry cleaning here? I’ll air them out for a few days and see what happens.

I’ve hired a Kazakh woman who normally teaches English to Kazakhs to be my Russian-teacher. She’s very friendly, and we’ve really hit it off. Today will be my first lesson — how to talk with Alexandra (e.g., “iron”, “wash”, “dust”, “not today”, “next time”, “kitchen”, “bedroom”, etc.). We’ve agreed I’ll set the agenda, so I can learn what I really need as fast as possible. She’ll come three days a week for an hour each day. Next time, I want to concentrate on the market — “apple”, “potato”, “eggplant”, “egg”, “how much?”, “too much!”, “good”, “no good”, etc. She’ll also accompany me as interpreter when I have to run errands; e.g., buying a new stove for the apartment (this one only runs on high), purchasing shelves for our home office, etc.

I’m already teaching myself the Russian alphabet: 32 letters, some of which have the same sounds as English (a, k, m, o, t). Others have the same sounds as Greek, so if you were a sorority girl, you know what they are. But others are completely new and may have sounds not found in English or even no sound. The latter are used to modify the sound of the letter next to them, making it hard or soft. I want to be able to read street signs as quickly as possible.

February 23

I’ve now seen five houses, none of which is really right for us, but I’m getting a useful impression of what’s available.

The house of R’s admin. assistant’s friend was a mixture of traditional and new, quite elaborate, a very modern design faced in pink stone with lots of marble here and there. The interior wasn’t practical from our standpoint; e.g, the master bedroom was on the top floor, with the nearest bathroom on the floor below, connected by a narrow, shallow staircase. If you had to get up in the night, you’d either break your neck or wet yourself before you got to the bathroom.

The wife of the Canadian Ambassador invited me to see her house in a neighborhood of new-builds — more Western in its layout but far too grand for our tastes. Today, we saw an older house, a cottage in the traditional Russian style owned by a Jewish couple who want to join their daughter in Israel. It was much more to our liking but too small for our needs. Best was the back garden with apple and pear trees, plus hen and goose houses. We found it charming and hope maybe there’s something larger in a similar vein elsewhere.

Appliance news: 1) The washing machine overflowed and flooded the apt — bad news, but good news too, because I met the project’s third Valodya. A computer engineer who’s not getting paid by his #1 job, “Valodya Electric” works as the project handyman, but even he was defeated by the “modern” machine. 2) They delivered a new Turkish stove to replace the Russian one that ran only on high.

February 28

Buying food is proving to be a challenge. No one store carries everything you need, and a store may be out of an item when you want it. So I wander from shop to shop, kiosk to kiosk, by foot on icy streets in the cold, carrying my shopping by hand and walking up four floors.

I’ve been taking tours of new houses of foreigners who’re here as diplomats, bankers or reps of international corporations as examples of what’s being built for expats and rich Kazakhstanis. For instance, the house of the local head of Chevron has a kitchen that was designed and built in London and shipped here — like something out of Architectural Digest. Three floors of ostentatious architecture, including a gym, a spa and a greenhouse. More clear to me than ever that I don’t want to live like some extravagant foreigner.

I also visited a traditional house for rent in a nearby village — pink stucco with gingerbread trim, two stories, an acre of land with fruit trees. When we first drove up, I thought, “This is it!” But a tour of the outbuildings (Russian banya, Finnish sauna, heated garage — very important in this climate) and then the house (walls almost two feet thick, three heating systems — gas, diesel and electric — so no matter what goes out, you’re still OK) made it clear that way too much money would be needed to fix all the problems. Sigh…

I may have found a house for us! A traditional cottage that’s been renovated, it’s been in a Russian family for three generations. 3/4 of an acre with lots of old trees, including fruit, next to a hillside with a creek running by, but right in Almaty. Russell could walk to work in clement weather. It’s very quaint and has the right amount of space for us. Before we can sign a lease, we would need to agree with the landlord about our paying for additional improvements, and the U.S. Embassy security officer would have to approve house and location. We’ve never had to get that clearance before, but now that R’s working in a U.S.-funded project, we come under Embassy jurisdiction. So it’ll be a while if it works out. Cross your fingers, toes and eyes that it does. It sure would be nice to be in our own house with our own stuff and get on with life.

COMING NEXT MONTH

Kazakhstan, 1995: Settling In

An appliance store opens in the basement of the Central Museum.

Creating a garden from a giant scrap heap.

Kazakhstan’s George Washington cuts down our cherry tree.

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.