#22: Guest Contributors

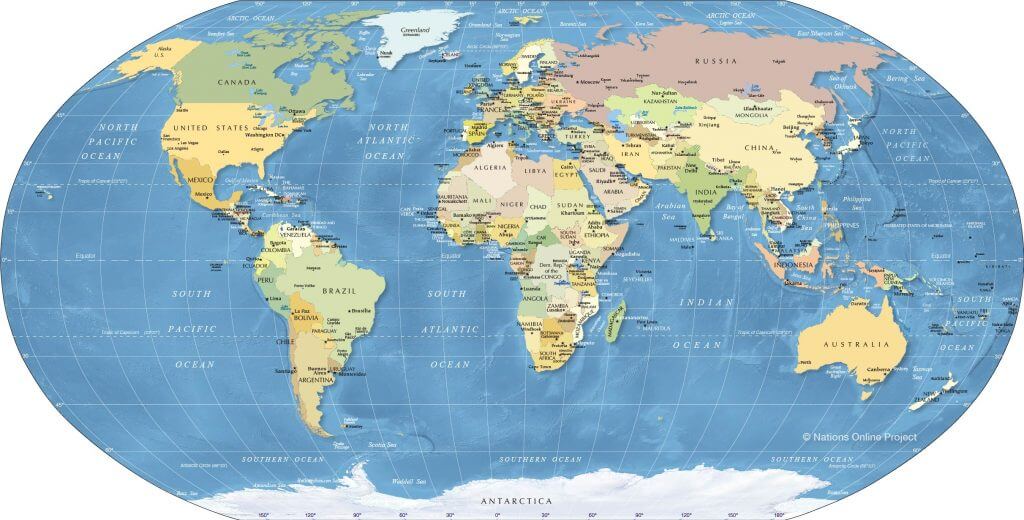

Time to share some more stories from others who’ve lived and worked abroad. The peripatetic life means you get to meet a lot of special folks. Here are a few, each one a jewel in my memory. [You can click on the map below in order to enlarge it for a clearer view of where their stories take place.]

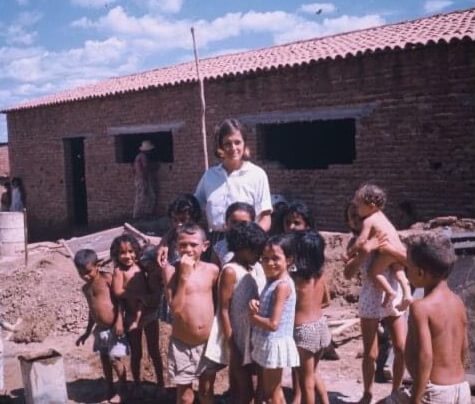

Michèle St. Clair: Brazil, 1970

By the second year of my Peace Corps term in Piancó, Paraíba state, my village was in the grip of famine. My first year had been dry and worrisome, but the second year of drought spelled disaster. People were dying; children died when they got a minor illness, even a cold. My miniature refrigerator was in constant use despite our erratic electrical supply, so my friends could use the ice to preserve their dead long enough for a proper burial.

Like everybody else, I was hungry most of the time. A friend in Recife, on the unaffected coast, suggested I take diet pills to ease the feelings of hunger. Unfortunately the combined effect of hunger and diet pills gave me a bleeding ulcer. Even now, I have frequent ulcer trouble.

Don’t think for a minute that Brazilians moan and groan about being hungry. No, they find someone who owns a guitar and they sing. Two-year-olds accompany the guitar by shaking match boxes in perfect rhythm.

One day I was walking through the town’s mostly empty marketplace, when I saw one man knife another to death so he could take his small bag of beans.

While this was going on, I’d started construction of an elementary school in the poorest neighborhood. I’d persuaded (more like extorted) the mayor to provide running water to the neighborhood, so we could mix it with cement. But the men and boys building the school frequently fainted from hunger on the job site. I went the 10 hours by bus to talk with my Peace Corps director about this. He arranged some Food for Peace for our use.

I hired a truck to carry the food to my village. For safety’s sake, I also hired armed guards, and we drove in the middle of the night.

We stored the bags of food at the back of my house, and once a week I distributed food to the men and boys who were building the school. It’s in use to this day.

A family particularly dear to me fell on extremely hard times. I helped support them after the father abandoned them. Each of three sisters lived with me at one time or another. This helped me protect my reputation, which was very important where husbands and fathers had the right to kill adulterous young women. But it also helped the family with living expenses. Towards the end of my two-year stay, the youngest sister was living with me. Nina was about six years old. One day, I found a can of sardines in tomato sauce that I’d brought back after a trip to the Peace Corps office. We were hungry and thrilled to find the sardines, but when I opened the can, it exploded, and tomato sauce went flying everywhere. I was going to eat the sardines anyway, but little Nina stopped me, to her everlasting credit.

Forty years later, I found the siblings of “my family” living in Brasilia (thank you, Facebook!). On my next trip to Brazil, I visited them. Two sisters and a husband met me at the airport. On the way to their home, I said I was taking the whole family out to dinner that night. The husband and I argued about who was going to treat the dinner, until finally he said very emphatically: “The woman who helped my wife stay alive is NEVER going to pay for a dinner with us.”

Michèle St. Clair worked in US government and politics during most of her career after Peace Corps, with occasional stretches of international development work and teaching. She lived in Spain as a child and later for eight years as the mother of her own child. Her international living experiences included Hong Kong and Laos, as well as other overseas locations. She’s now exploring and visiting Brazilian friends in Portugal with a view to moving there in 2022.

Mike Hager: Pakistan, 1971

It was August 1971. Pre-war tensions between India and Pakistan were heating up. Based in Islamabad as Regional Legal Advisor for the U. S. Agency for International Development, I covered Pakistan, Afghanistan and the former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

I had just arrived in Dacca on a work mission and checked into my hotel at a quarter to midnight when the telephone rang. A voice from a U.S. Embassy colleague in Pakistan said: “Kristen is in the hospital. She’s receiving full medical care. Please come home immediately.” This news came as a terrible shock. Only a few hours earlier I had left my wife, June, my three-year old daughter, Ashley, and our 18-month-old daughter, Kristen — all of them in apparently good health. Now suddenly Kristen’s life appeared endangered from cholera or something similar.

Since India had banned Pakistan International Airlines flights, the soldiers (who filled most of the seats) and I had to fly south, over Sri Lanka, a several-hour detour. Arriving in Karachi and connecting to a flight in Lahore, I didn’t reach the hospital in Islamabad until mid-afternoon.

One look at my emancipated daughter convinced me that we had to find more advanced medical treatment for her. The U.S. Embassy physician agreed. He arranged for Kristen to be admitted to the American University of Beirut Hospital. The next morning, our family of four, along with the doctor, flew to Beirut, where Kristen spent ten days in the ICU and the rest of us (except the doctor, who took the return flight back to Pakistan) resided at a hotel close to the American Embassy.

June, Ashley and I celebrated when Kristen emerged from her eleventh day of medical confinement smiling and hungry. By this time, June was over 7 months pregnant and would not be allowed to board a plane. She would need to give birth at the hospital that had cured our daughter. Meanwhile, the USAID Mission Director was calling for my return to Pakistan. Reluctantly, I left my wife alone to care for the girls.

The babysitter we had hired quit suddenly, and an hour later June went into labor. Leaving the girls at the hotel reception, she managed to arrange for the American Embassy women’s club to host the children. Then she took a taxi to the hospital and gave birth to our son, Tariq — all within a couple of hours. Leaving the hospital after a day, she secured a passport for Tariq and plane tickets before retrieving her son three days later from the hospital on the way to the airport and back to our home in Pakistan.

Mike Hager is a retired USAID officer who served in Pakistan, India and Egypt. He co-founded the International Development Law Organization in Rome and was founding president of the Education for Employment Foundation, which trains youth for jobs in the Middle East and North Africa.

Joan Lowell: Kazakhstan, 1994

“Kazakhstan wants you.” April 1994: the Peace Corps recruiter was calling to tell husband Irving and me that we’d been selected to serve as Business Development Volunteers in Kazakhstan. We left the dinner table and rushed to the library to find out where Kazakhstan was! A brand new country in Central Asia, recently separated from the former Soviet Union. Very excited, we immediately called our three daughters to give them the news.

By December we were living in Semipalatinsk, very northern Kazakhstan, in Siberia, helping people create businesses. We’d had our three months of language training (Russian and Kazakh) and our intro to the culture. I was almost 60 and Irving was 65 years old. We were living our dream of 17 years.

By December we were living in Semipalatinsk, very northern Kazakhstan, in Siberia, helping people create businesses. We’d had our three months of language training (Russian and Kazakh) and our intro to the culture. I was almost 60 and Irving was 65 years old. We were living our dream of 17 years.

The days were dark until about 10:30am and dark again by 4:30pm. Temperatures were often below zero. On the morning in question, Irving was out of town, so I was working alone. Around 9am, I walked the half-mile to our office and entered the elevator. As the door closed, the lights went out and the elevator didn’t move. Panicky, I reached out to press several buttons, and the power came back on.

When I arrived at my office, I found a young woman waiting for an interview to be our interpreter. We entered the office and began to talk. She didn’t understand most of what I said. I knew she wouldn’t be suitable for the job. After a few awkward minutes, she left and I went on with the matters of the day.

About 4:15, I started the walk home. It was almost dark and very cold and as I walked, I thought, “If anything happens to me, my Russian isn’t good enough to tell someone what’s wrong.” I arrived at our building and climbed the five flights to our apartment. As I went in, the delicious warmth hit me, and I began to cry uncontrollably. My chest started to hurt and I couldn’t stop sobbing. I recalled that my father had died at 49 and my brother had died at 50, both of sudden heart attacks. My chest hurt more, and I feared, “This is it.”

I reached for the book Peace Corps gave Volunteers, “Where There Is No Doctor”*. Still sobbing and shaking, I looked up “Heart Attack” and scanned the page, reading that someone with severe chest pain should stay in bed. I burst out laughing at the absurdity. If I was really in the midst of an active heart attack, how could that save me?

The realization gave me some perspective and broke my panic attack. I called the Peace Corps medical officer in Almaty and my Kazakh counterpart in Semipalatinsk. They offered to arrange for me to fly to Almaty the next morning. Knowing that, the pain and panic left. I felt thankful, ready to stay and continue my work.

Joan Lowell left her position as CEO of a nationally recognized hospice to serve with her husband in Kazakhstan as Peace Corps business development volunteers. Currently, Joan is an academic associate at Arizona State University.

———-

*Hesperian Foundation, 1992

Ben Steinberg: Armenia, 1994

Navigating the narrow winding streets in Armenia’s hilly capital long before smart phones and mobile maps, I wasn’t sure of my directions.

I was hoping to find something exciting to bring home to my partner, Alexandra. But at this rate… I rounded a bend and lost my doubts about finding the place. Cars had been jammed at every possible angle against the stone walls and metal gates that lined the roadside. I crept onward until I found a square to squeeze in our small Russian jeep.

Walking back to my destination, I wondered if all the expatriates in the country had arrived before me. German, Russian, and French hit my ears, as well as English spoken in at least five accents. Judging by the size of the crowd, I wasn’t the only one eager to sift through the remnants of a departing American Foreign Service Officer’s household — everything they couldn’t ship, up for sale. Outside, tables were piled with children’s clothes, kitchenware, sports equipment, car parts, imported foods like maple syrup and chocolate chips. Inside, they were selling some furniture, a washing machine and dryer. Most of the items were from the U.S., not available in Armenian shops.

I imagined the best treasures already scooped up, but among the small appliances, I spotted an electric hand mixer. Jackpot!

Then I noticed another man had also fixed his eyes on it. He brushed aside my dismay with friendliness. “The way you’re inspecting that mixer, you must be a real cook.”

“We do like our food,” I replied, knowing it was a source of comfort in our lives overseas. While we enjoyed exploring local cuisines, we longed for foods we couldn’t get locally. So we learned to cook what we couldn’t buy. Alexandra was the only expat I knew who created homemade bagels in Kazakhstan, sushi in Tanzania, and vegetable mushu in Armenia. We even planned our hikes around what would be included in our picnic basket.

I brought myself back to the moment, the mixer, and the man beside me. Paul and I hit it off, laughing and teasing each other easily. Overseas posts typically last about two years, and it’s hard to get the timing right to build a friendship with other expats. I asked the ever present question “How much longer do you expect to be here?”

“Well, you never know for sure, but I think it should be two years or so. I just arrived last month.” He paused. “You take the mixer. I can always bring one from Germany.”

I accepted the offer on two conditions: that he come over for dinner sometime that week and that he satisfy my curiosity about his reference to Germany. I’d pegged his accent as either American or possibly Canadian, and “Germany” threw me.

Turned out Paul was American with Germany as home base after a long stint there advising on privatization of what had been East German assets. Now he was flying back and forth between Germany and Armenia every two weeks. I mumbled something about perpetual jet leg. He laughed and said that when he woke up every morning, it took him a moment to place which country he was in.

Paul was the real exciting find I brought home to Alexandra. I couldn’t anticipate at the time that this budding friendship would be one of a precious handful that survived the disruption of frequent foreign moves and the challenges of long-distance communication. I only knew that Paul would be one of the lights in our time in Armenia.

Retired microfinance, and community development specialist Ben Sternberg worked internationally in Kazakhstan, Hungary, Armenia, and Tanzania. Returning to the USA, he was president of Southern Bancorp Capital Partners, managing mission-related activities for the then-largest rural development bank in the United States. He also served as Board Chair of ScholarMatch, a San Francisco-based non-profit providing scholarships and wraparound services to underserved and first generation students.

**********************

HAVE YOU LIVED AND WORKED OVERSEAS?

DO YOU HAVE A STORY TO SHARE?

PLEASE CONTACT ME VIA nancy@nancyswing.com.

I’D LOVE TO CONSIDER YOUR STORY FOR THE NEXT GUEST CONTRIBUTORS POST.

POSTSCRIPT:

I was finalizing this post as the old year ended and the new one began, deeply moved by the recent loss of two friends from the international life: John Gruszka of our East Africa years and David Benedetti sharing our Kazakhstan sojourn. Two good men, gone too soon.

(If these names look familiar, both have appeared in previous blogs — John was the husband of Fern, who wrote a piece as a guest contributor in Post #15, and Dave’s comments about the risk of becoming inured to the sights of daily life graced Post #8.)

COMING NEXT MONTH

Living and working overseas is very different from being there as a tourist.

However, living and working overseas means you also get to be a tourist.

Touristing in Southeast Asia: Luang Prabang, Laos and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

LET ME HEAR FROM YOU.

Please take a moment to share your thoughts.

Your comments help make the blog better, and I always answer.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this post, I hope you’ll SUBSCRIBE by clicking on the button below. Every month, when I post a new excerpt from my life overseas, you’ll get an email with a link so you can read the next installment. Subscription is free, and I won’t share your contact information with anyone else. Your subscribing lets me know you’re reading what I write, and that means a lot.